Georgia’s closest brush with actual combat operations in World War II (1941-45) occurred when American air and naval forces battled prowling German U-boats along the state’s Atlantic coastline. In 1941 Germans sank five Allied merchant ships off Georgia shores. By late 1943, however, Georgia’s coastal defenses had grown so formidable that German submarines no longer entered the state’s waters.

Georgia’s Defenses

Georgia’s waters were initially considered an unlikely target for enemy submarine attacks. First, the state’s coastline is relatively short, stretching approximately 100 miles between the South Carolina and Florida borders. More important, the continental shelf off Georgia’s coast is extremely shallow; submerged German U-boats would have only a few feet of water over their conning towers, making them vulnerable to being spotted and attacked.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

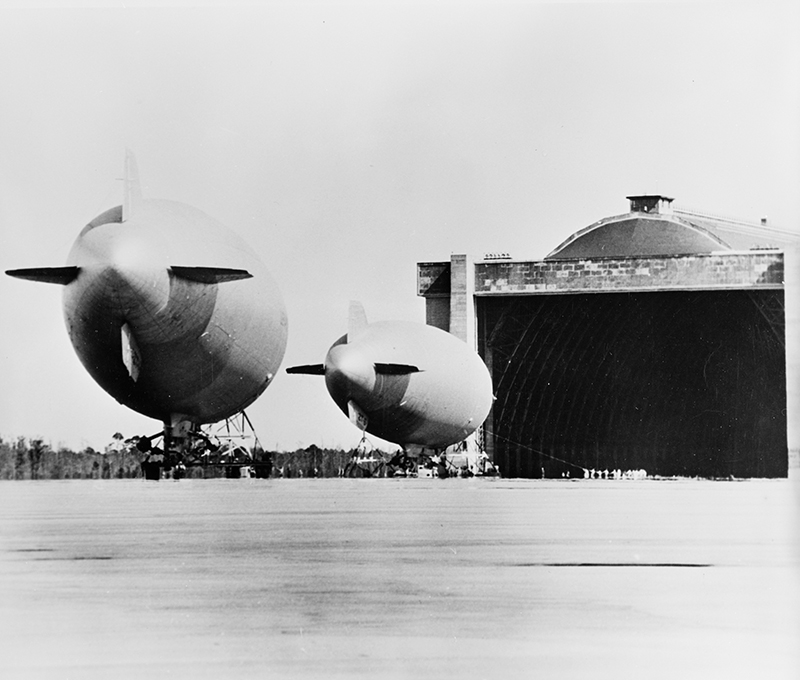

Aside from geographic factors, Georgia was relatively well defended. Because of its economic and industrial importance to the American war effort, the state was the site of several large military bases. Most important to the antisubmarine effort were Chatham and Hunter airfields, both located near Savannah. One of the most effective military bases in the U-boat war was Glynco Naval Air Station, located near Brunswick and home to both fixed-wing and lighter-than-air antisubmarine aircraft. The port of Savannah itself hosted an assortment of small coastal patrol and antisubmarine warships.

War Comes to Georgia’s Shores

Despite elaborate prewar plans for the defense of Georgia’s coastline, the area was still vulnerable to attack when the United States entered World War II. Early antisubmarine patrols were sporadic and uncoordinated, and many Georgia coastal communities disobeyed orders for nighttime blackouts. The defenders were shaken from their complacency, however, when the U-boat threat finally hit home in the spring of 1942.

Photograph from German Federal Archive

Lieutenant Commander Reinhard Hardegen, skipper of the German submarine U-123, had already drawn Georgian blood in January 1942, when his U-boat sank the freighter City of Atlanta off the coast of Cape Hatteras, North Carolina. The 5,200-ton merchantman was based in Savannah, and many of the forty-three sailors who died in the attack were residents of the city. On his next war patrol two months later, Hardegen once again steered his submarine from its base at Lorient, France, toward the United States. Sailing southward down the Eastern Seaboard, the U-123 sank four ships before entering Georgia’s waters.

The U-123 moved to a position in the shallow waters just off St. Simons Island. In the early morning hours of April 8, 1942, the Germans spotted a large tanker silhouetted against the illuminated shoreline. Hardegen fired a torpedo and sank the 9,200-ton oil tanker Oklahoma. Less than an hour later, he spotted and sank another tanker, the 8,000-ton Esso Baton Rouge. The next morning, the U-123 sank a third ship, the steamship SS Esparta, about fourteen miles south of Brunswick. Hardegen then sailed south to prowl Florida waters, where he sank four more ships before returning to base.

A total of twenty-three crewmen aboard the three vessels sunk in Georgia waters were killed in the attacks. Survivors from the ships were rescued and brought to shore by several U.S. Coast Guard ships and a private yacht owned by Charles Howard Candler, the son of Coca-Cola Company founder Asa Candler. The two tankers, sunk close to shore in shallow water, were eventually salvaged and refloated. After extensive repairs both ships rejoined the war effort. Later in the war the two ships were again sunk by U-boats, this time permanently.

Georgia Reacts

The attacks along Georgia’s coastline threw the state into a panic. The gigantic blasts from the exploding tankers had shattered windows in nearby Brunswick, and thick oil fouled beaches in the area for weeks afterward. Frightening rumors of Germans landing on shore began circulating throughout the coastal communities.

The administration of U.S. president Franklin D. Roosevelt acted decisively to end the U-boat threat along the Atlantic coastline. The U.S. Navy adopted the British system of convoying ships, and air and naval patrols were increased. Most important for the defense of Georgia, the submarine-hunting blimps of Airship Squadron ZP-15 were stationed at Glynco Naval Air Station, providing around-the-clock protection against U-boats.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

Georgia’s coastal defenses grew so formidable that enemy submarines never again dared to come within sight of land. During the summer of 1943, two more American tankers were sunk approximately 150 miles east of Brunswick. But by then the tide of war had turned against the U-boats. The hunters became the hunted, and the German U-boat threat in Georgia waters ended for good.