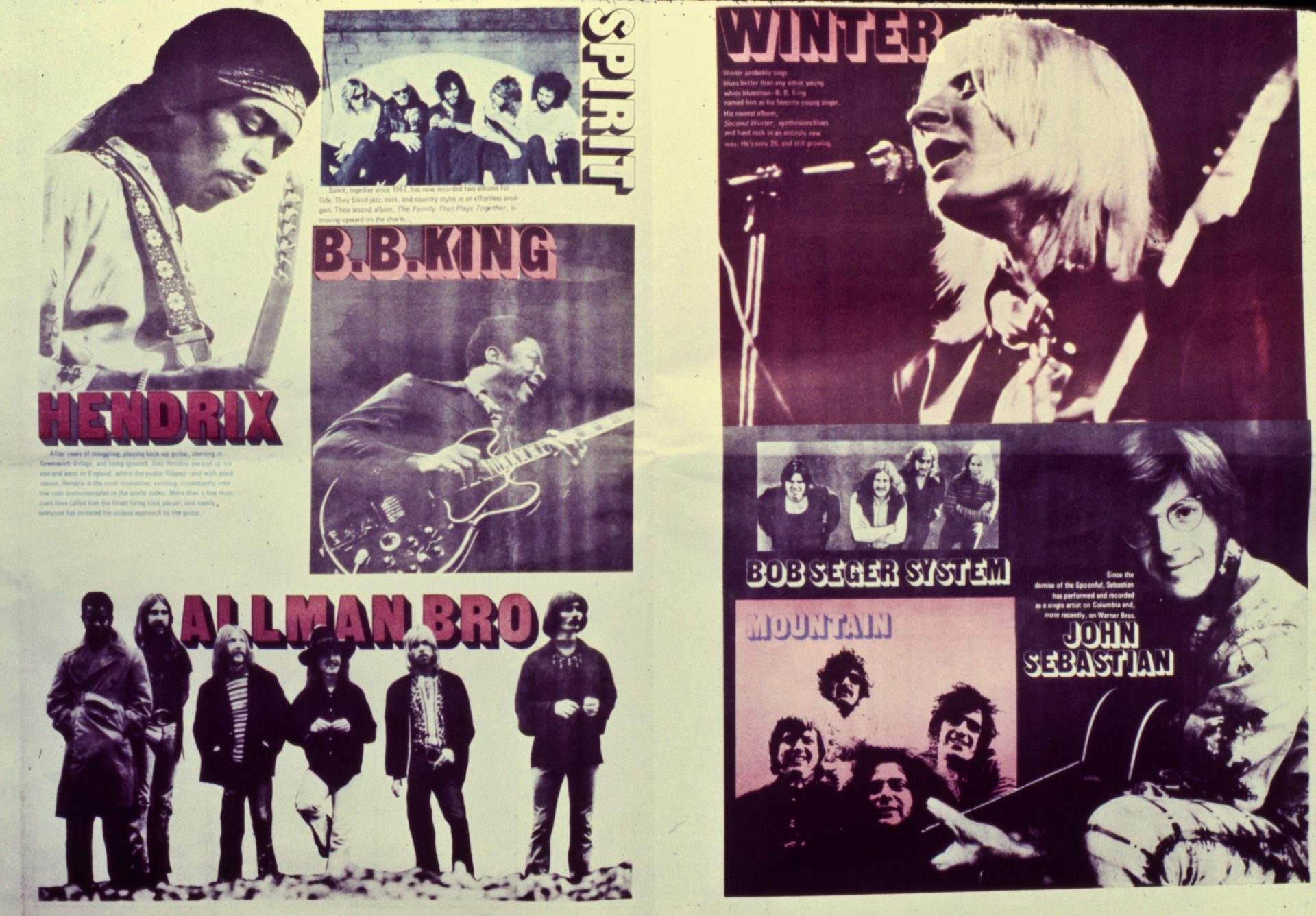

The Atlanta International Pop Festivals of 1969 and 1970 drew hundreds of thousands of music fans to Georgia, launched the career of concert promoter Alex Cooley, and featured musical performances by Led Zeppelin, Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix, and the Allman Brothers Band.

Hampton

The first Atlanta International Pop Festival was held on July 4-5, 1969, at the Atlanta International Raceway (later Atlanta Motor Speedway) in Hampton, Henry County. Coming a month and a half before the famed Woodstock festival in New York, the Atlanta pop festival was the first of its kind in the Deep South.

The festival was the brainchild of promoter Alex Cooley, who had been inspired by his experience at the Miami Pop Festival in December 1968. When searching for investors, Cooley learned of another group, led by Chris McLoughlin, Robin Conant, and Fred Lagerquist, who were also planning to stage a festival in Atlanta. The two groups combined their efforts and eventually assembled a large team of investors to finance the 1969 festival.

More than 100,000 music fans crowded the infield of the Atlanta International Raceway to see marquee acts like Janis Joplin, Creedence Clearwater Revival, and Blood, Sweat & Tears. The lineup also featured several newcomers, including Grand Funk Railroad, Led Zeppelin, and the Chicago Transit Authority (later Chicago). Despite the relentless heat, insufficient concessions, and inadequate water supply, the festival was a financial success, demonstrating that Atlanta and other Deep South sites were viable destinations for national and international touring acts.

Byron

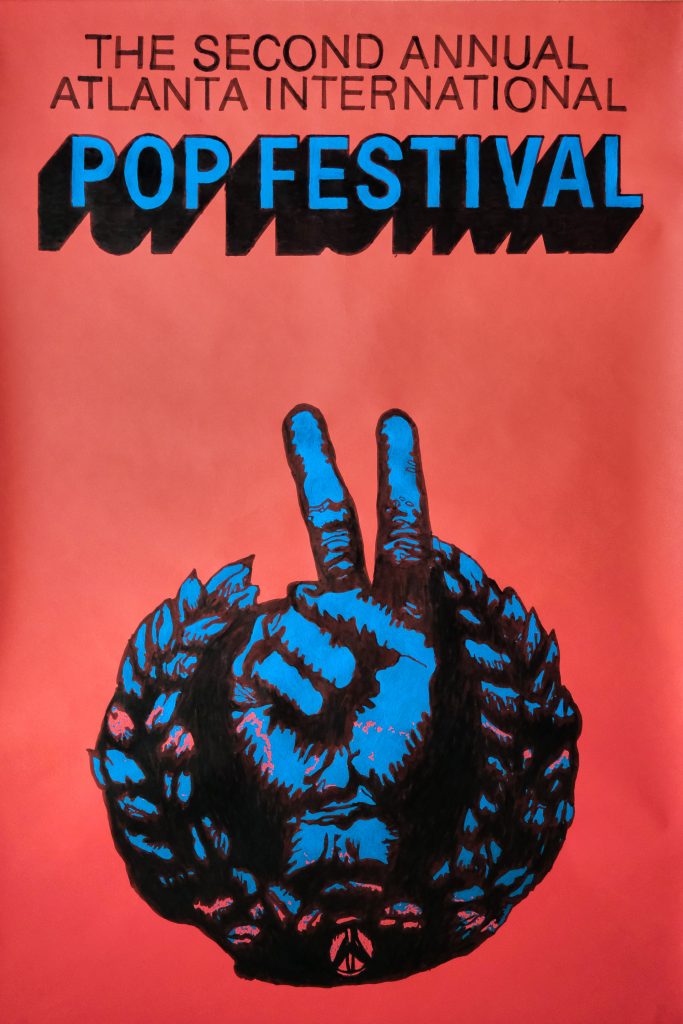

In July 1970, Cooley and a small team of investors staged the second Atlanta International Pop Festival at the Middle Georgia Raceway in the small rural community of Byron, Peach County, about ninety miles south of Atlanta. To avoid the financial losses that marred Woodstock and other festivals, the organizers fenced the perimeter, ensuring that only ticket holders could enter the premises. They learned from their own errors as well, securing enough food and water to accommodate between 100,000 and 150,000 people.

But despite these efforts, Cooley and his colleagues were unprepared for the masses that descended on tiny Byron. Estimates vary, but the festival likely attracted between 200,000 and 300,000 people. Food and water were scarce by the end of the first day, and the free, second stage erected by Cooley and his team failed to satisfy the tens of thousands of ticketless concertgoers who demanded entry, shouting “free concert! Music is for the people!” To prevent violence between gate crashers and the bikers hired to guard the entrances, the organizers opened the gates and declared the festival free to all—a decision that avoided the bloodshed that doomed a similar event in Altamont, California, in December 1969, but also ensured that Cooley and his partners would suffer financial losses.

Governor Lester Maddox, a fierce critic of the festival, sent dozens of state troopers to Byron to enforce state drug laws. Because of the crowd size, the officers could only direct traffic and provide assistance where needed. Consequently, marijuana, LSD, and other illegal substances were openly used and purchased.

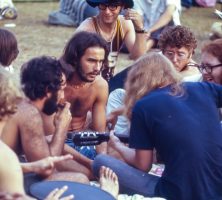

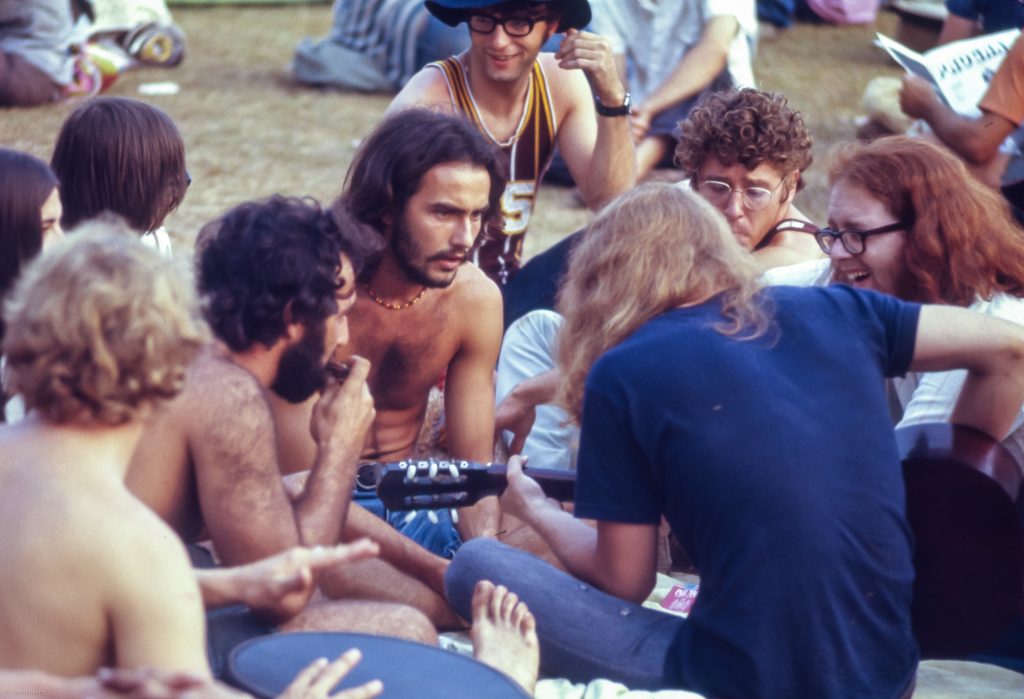

As temperatures hovered around 100 degrees, firetrucks were brought in to hose down the crowds, and many attendees frolicked in the nude or swam in nearby creeks and lakes. The medical staff worked around the clock to treat thousands of cases of sunburn and lacerated feet and to alleviate the side effects of drug use.

News stories about the Byron pop festival tended to focus on the drugs and nudity while giving short shrift to the music, which included performances by B.B. King, Procol Harum, and Johnny Winter, among many others. The Allman Brothers Band played two sets at the festival, and the event’s biggest draw, Jimi Hendrix, performed the “Star-Spangled Banner” in the wee hours of July 5, as fireworks erupted overhead.

Despite the event’s many challenges, a spirit of cooperation prevailed for much of the weekend. Local farmers brought in truckloads of watermelons and cantaloupes to distribute, attendees waited patiently for water, and there were few incidents of violence. Like other festivals, Byron offered attendees a chance to experience the counterculture firsthand, providing a sense of community that, however briefly, transcended race, region, and social class.

End of the Festival Era

There were many critics of the 1970 Atlanta pop festival. Church leaders, concerned parents, and others were horrified by reports of widespread drug use and nudity and demanded that elected officials prevent another festival. In 1971 the General Assembly passed a law that made it next to impossible for promoters like Alex Cooley to stage another such event. According to the act, festival organizers would now have to submit a request to the Georgia Department of Public Health and undergo a rigorous application process before receiving approval. They were also required to construct water and sewage facilities, draft detailed plans for emergencies, and provide a bond of $1 million issued by a surety company. The act was signed into law by Governor Jimmy Carter and made future rock festivals significantly more difficult to produce.