Bilali Mohammed, an enslaved African who lived openly as a Muslim on Sapelo Island, has been a subject of scholarly and popular interest since the nineteenth century. His experience is reflected in the “Bilali Document,” a brief manuscript he wrote concerning Islamic regulations.

Life

Commonly referred to today as Bilali, but also known in the historical record by such names as Bel-al-i and Bu Allah, Mohammed was born in Timbo, in the Fouta Djallon (Futa Jallon) region of what is now Guinea in West Africa. This area was a Muslim center and all indications are that Mohammed received an Islamic education there.

It is uncertain when Mohammed was taken from Africa. He was first enslaved in the Caribbean. Sometime around 1803 he and members of his family were bought by Thomas Spalding, an agriculturalist and politician, who took them to Georgia. Prior to his enslavement in Georgia Mohammed had married a woman named Phoebe, and they were able to bring several daughters with them to Georgia but apparently no sons.

Spalding came to use Mohammed to supervise hundreds of other enslaved persons on Spalding’s extensive property on Sapelo Island, a barrier island near mainland Darien. There they focused on the cultivation of Sea Island cotton, sugar cane, and other secondary crops, as well as lumbering.

Remembrances of Mohammed and his family indicate that on Sapelo Island they lived publicly as Muslims in the face of a predominant Christian culture. Historian Allan D. Austin summarized Mohammed’s habits and customs: “He regularly wore a fez…he prayed facing the East on his carefully preserved prayer rug, and he always observed Muslim fasts and feast-day celebrations.” It should be noted that Phoebe joined her husband in prayer three times a day, using a string of beads. Austin added that Mohammed was buried “with his rug and Quran.”

Much has been made of Mohammed’s role during the War of 1812. Spalding gave Mohammed eighty or so muskets to use with other enslaved persons to defend Sapelo Island against a potential British landing. That Mohammed was so entrusted by Spalding has suggested to some that the two had a close relationship.

Mohammed and Spalding did not, however, have a comparable power dynamic. Spalding was known to be “quick-tempered” and Mohammed must have had to walk a fine line to negotiate with him. Without doubt, Mohammed had a strong spine and spirit. As historian Melissa L. Cooper has put it, “the fact that Mohammed…did not surrender his religion is in and of itself an act of resistance.”

When Spalding died in 1851 his will granted Mohammed manumission. Late in life and in poor health, Mohammed moved from Sapelo Island to the mainland and died around the age of eighty. His burial place is unknown.

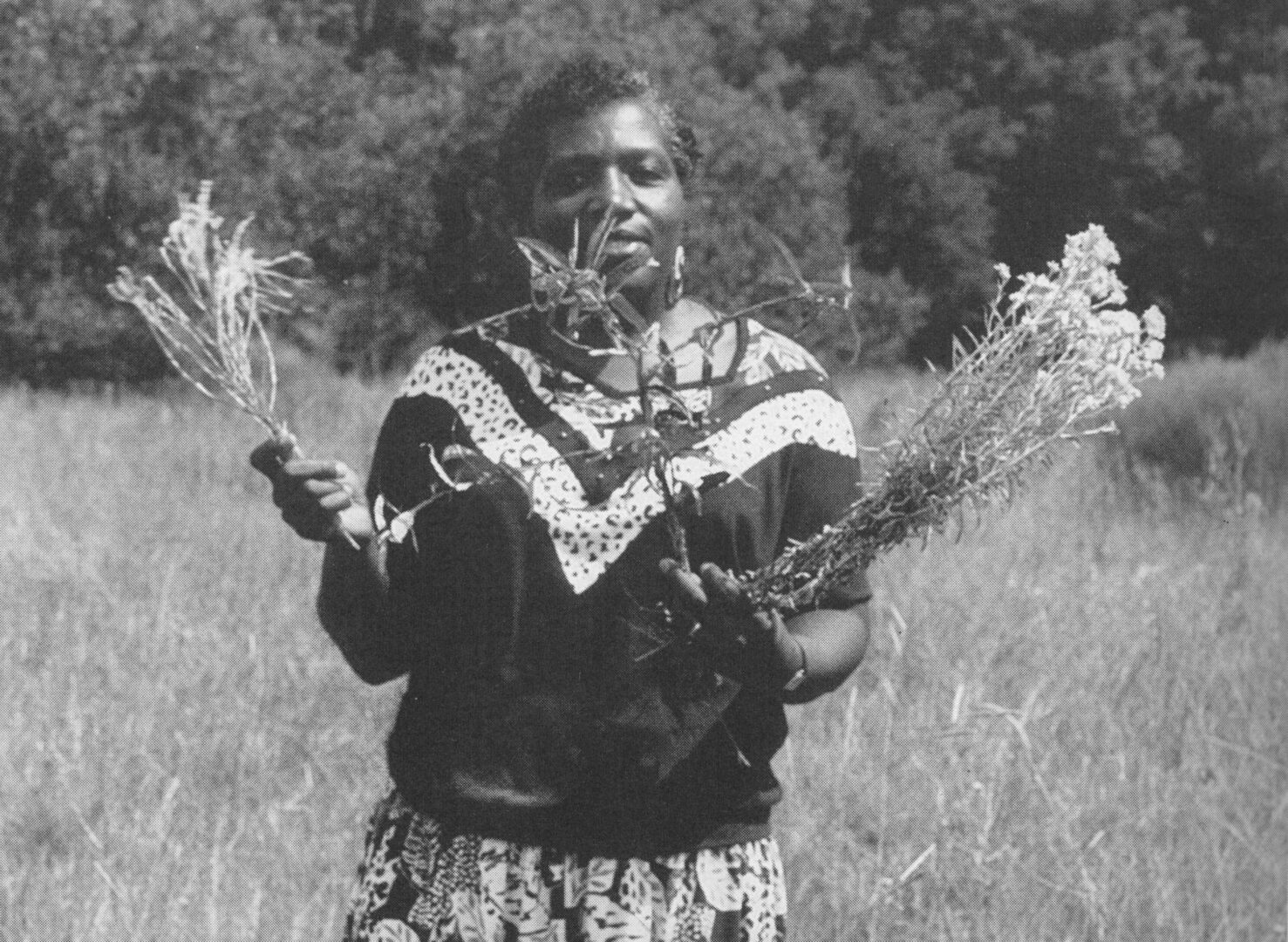

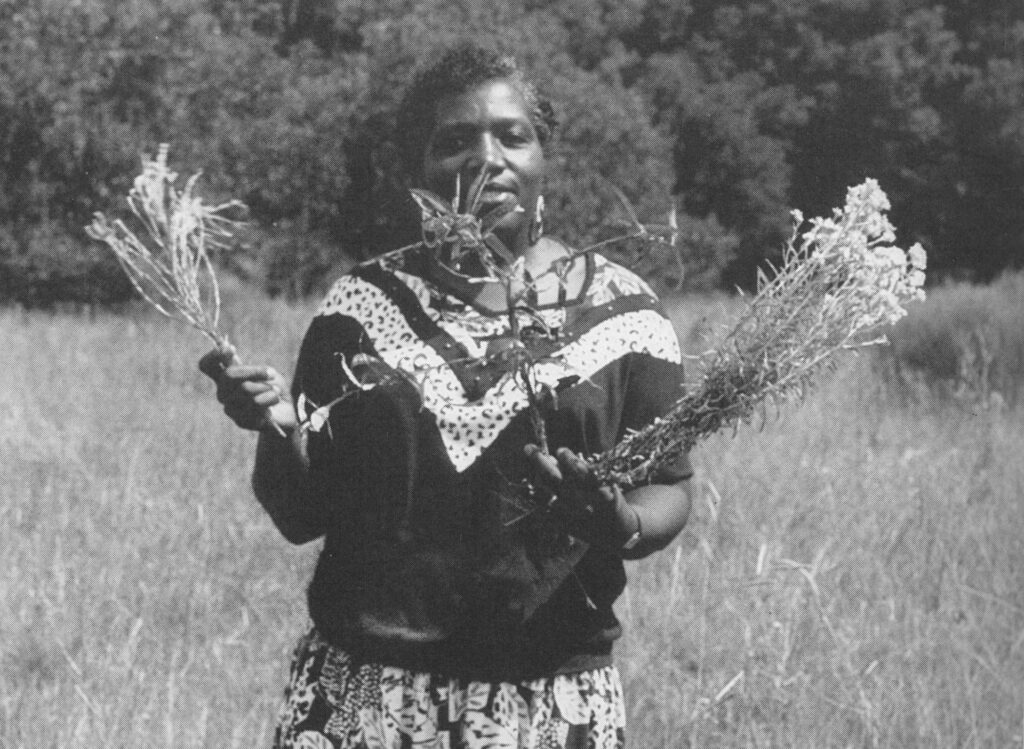

Numerous residents of Sapelo Island have been direct descendants of Mohammed, notably the author and cultural advocate Cornelia Bailey. Indeed, on the opening page of her book God, Dr. Buzzard, and the Bolito Man: A Saltwater Geechee Talks About Life on Sapelo Island (2000), Bailey referred to Mohammed as “the first of my ancestors I can name.”

Manuscript

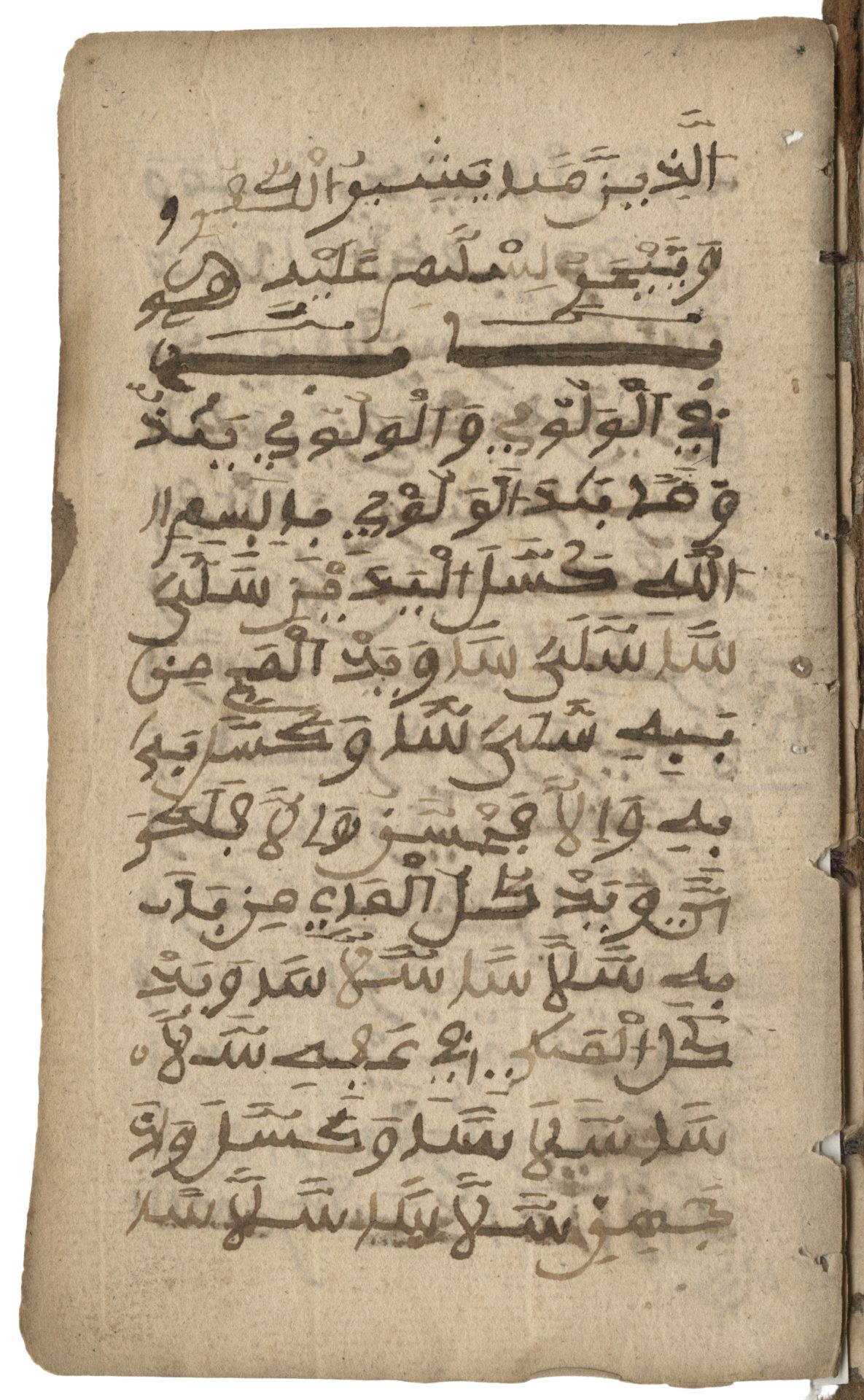

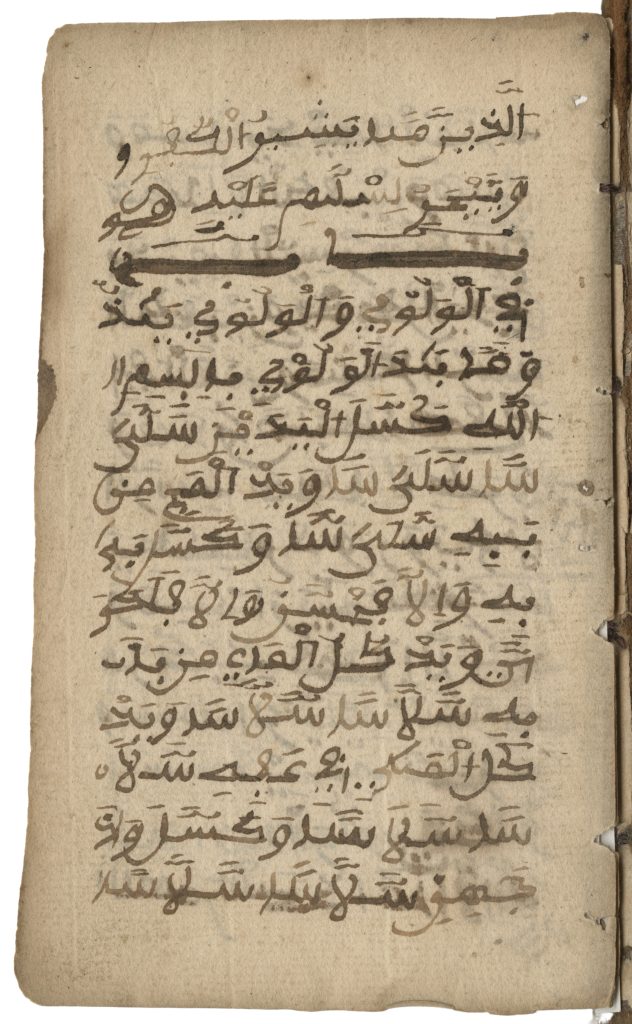

Bilali Mohammed possessed a small, leather-bound manuscript with Arabic lettering. This thirteen-page document is now housed in the Hargrett Rare Book & Manuscript Library at the University of Georgia.

One of the first scholars to study the manuscript was Joseph H. Greenberg, who published a brief analysis of it in 1940, “The Decipherment of the ‘Ben-Ali Diary,’ a Preliminary Statement.” Though the document was originally referred to as a personal diary or a plantation journal, it is clear that it should also be considered as an Islamic text.

Deciphering the manuscript has remained a challenge both because ink has bled from one side of a page to the other and because at least one double-sided page is missing. Nevertheless, those who have examined it have been able to translate nine complete pages and sections of the remaining pages. The surviving material suggests a high degree of Muslim piety. In the main, the document records fundamentals of Islamic belief, how to properly perform ablutions, and procedures governing prayer.

According to Muhammed Abdullah Al-Ahari, one of the most recent researchers to inspect the manuscript, it is “the only extant work on Islamic Law written during the time of slavery in North America.” As such, Al-Ahari asserts that Mohammed “is the Father of American Islamic Literature…since he was the first individual to compose an American Islamic text.”

Legacy

American literature has portrayed Bilali Mohammed in divergent ways. In the late nineteenth century, the Georgian author Joel Chandler Harris (of “Uncle Remus” and “Brer Rabbit” fame) drew upon stories about Mohammed to form the basis of an imagined figure, Ben Ali, represented by Harris as a “slave hunter,” who himself became enslaved and who had a leather-bound “memorandum book” in a “strange tongue.” A fictional son of this character called Aaron first appears in Harris’s The Story of Aaron (So Named), the Son of Ben Ali (1896).

During the early twentieth century, some researchers became interested in chronicling the experiences of formerly enslaved persons and their relatives. As part of this effort, the Georgia Writers Project (associated with the federal Works Progress Administration) interviewed several persons on Sapelo Island in the 1930s, including two great-grandchildren of Mohammed, Katie Brown and Shad Hall. Their accounts of family memories are recorded in Drums and Shadows: Survival Studies Amongst the Georgia Coastal Negroes (1940).

Finally, several recent Black women writers have been inspired by the figure of Mohammed. Melissa L. Cooper observes that in Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon (1977), Paule Marshall’s Praisesong for the Widow (1983), and Gloria Naylor’s Mama Day (1988), “Bilali Mohammed becomes the ancestor of every African American in search of a forebear who resisted white cultural hegemony by passing down to his children sacred beliefs and practices.”