Ed Moulthrop, a self-taught wood turner who made his home in Atlanta, was considered a master craftsman. His turned bowls are characterized by their large sizes, typically spherical or elliptical forms, and highly polished, clear finishes. Wood turning is a process in which a piece of wood is spun on a lathe (a machine that rotates an object on a fixed axis) and shaped with a tool drawn against it.

Edward Moulthrop was born in 1916 in Rochester, New York, and brought up in Cleveland, Ohio. He developed an interest in wood turning as a teenager and sold magazines to earn money for his first lathe. He received his undergraduate degree from Case Western Reserve University in Ohio in 1939 and his graduate degree in architecture from Princeton University in New Jersey in 1941. After completing school he taught architecture at the Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta and then practiced as an architect. Wood turning remained a strong interest of Moulthrop’s, though it was only a side activity during his time as an architect. In the early 1970s he set aside his architectural career and became a wood turner full time.

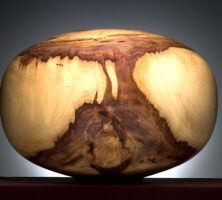

Moulthrop’s turned wood bowls reach up to forty inches in diameter and four feet in height. These large sizes necessitated his development of a special lathe and long-handled tools fit to turn wood on such a scale. Moulthrop also developed methods for strengthening his wood and for creating a plastic-like finish. He turned the wood to create a rough form, which he then soaked in polyethylene glycol from a period of six weeks to three months. This chemical fixed the wood’s color and replaced the natural moisture, stabilizing the material and preventing shrinkage and cracking. Next, he turned the treated vessel to create a finished form, which he coated with resin.

Like noted wood turners Rude Osolnik and Melvin Lindquist, Moulthrop often used wood that earlier turners would have considered flawed. He frequently used wood that was diseased, struck by lightning, or streaked and discolored because of fungal growth. Such natural variations in the wood resulted in turned bowls with interesting patterns and colors. He sought to find shapes and finishes that revealed “the myriad complexities, the subtle or exotic range of colors, and the etching-like patterns of growth rings” in the wood. Also, Moulthrop’s method of treating wood allowed him to use pieces that otherwise might have been too fragile.

Moulthrop’s work is represented in the collections of many major museums, including the Museum of Arts and Design, the Museum of Modern Art, and Metropolitan Museum of Art, all in New York City; the Art Institute of Chicago; the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston; the Detroit Institute of Arts; and the Smithsonian Institution’s Renwick Gallery in Washington, D.C. Eight of his pieces are included in Georgia’s State Art Collection.

Moulthrop died in November 2003 after a long illness.