Francis Fontaine, an aristocrat possessed of a cultivated mind and brilliant conversational abilities, was a Renaissance man of nineteenth-century Georgia. A fearless Confederate soldier, a newspaper editor, Georgia’s representative to the Paris Exposition, a delegate to the state constitutional convention of 1877, and a force in Atlanta real estate and lending concerns, he is best remembered for his literary endeavors.

Born May 7, 1845, in Columbus to John Fontaine, first mayor of that city and one of Georgia’s leading entrepreneurs, and his wife, Mary Ann Stewart, Francis Fontaine was a student at the Georgia Military Institute in Marietta when the Civil War (1861-65) began. Though only a boy, he enlisted in the Confederate army and served throughout the war as a private and aide-de-camp, even after suffering serious hearing loss in the field. He distinguished himself in a number of battles, most notably at the Battle of Peachtree Creek. There he took the flag from the wounded standard bearer and spurred his horse in advance of his comrades toward the enemy line, rallying the dazed, retreating Confederate force as his horse was shot from under him. After the defeat of the Confederacy at Appomattox, Virginia, Fontaine returned home to Columbus and managed his father’s vast planting interests.

In 1874 he and an associate founded the Columbus Times. And although Fontaine had no previous political experience, in 1877 he was elected to represent his district at the convention to draw a new state constitution.

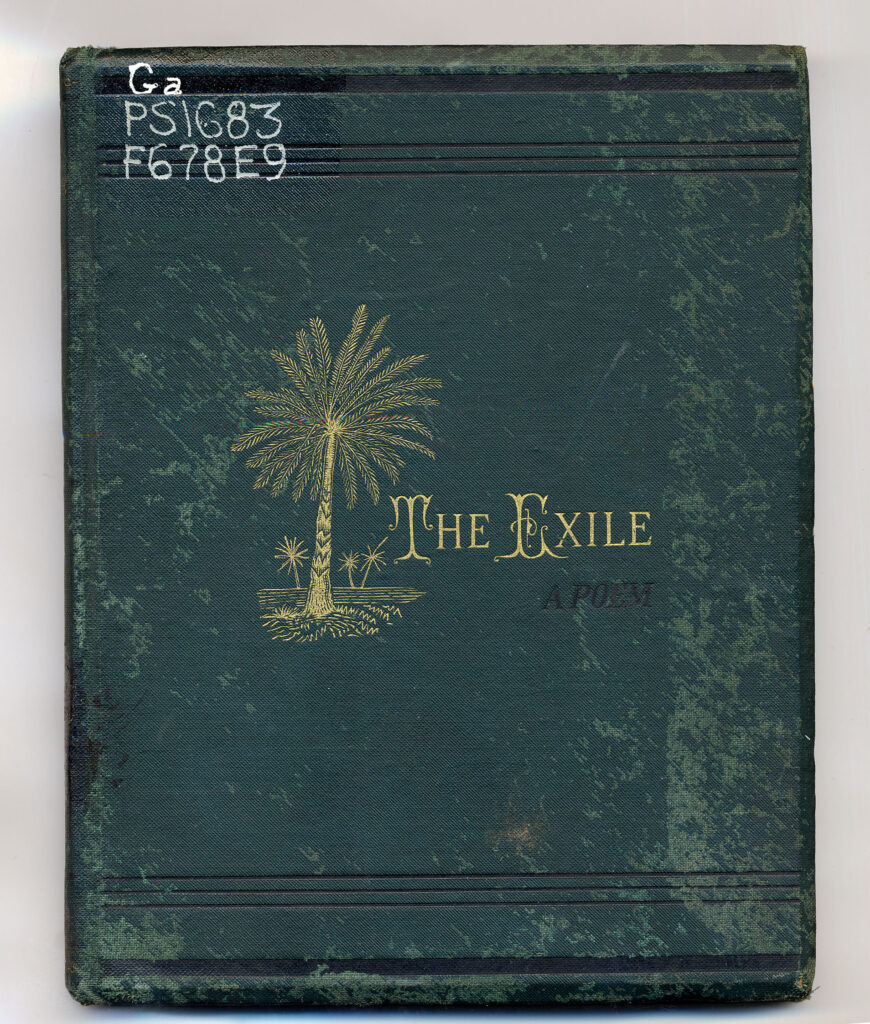

The following year G. P. Putnam’s Sons in New York published his narrative poem The Exile: A Tale of St. Augustine, treating the Florida massacre of Huguenots by the Spanish in 1565. Before publication Fontaine sought the advice and approval of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, whose own long poems had provided Fontaine a model. Both Longfellow and reviewers in the New York Times and the Evening Post found little merit in the work, and subsequently Fontaine turned his attention to prose.

His next publication, The State of Georgia: What It Offers to Immigrants, Capitalists, Producers and Manufacturers, and Those Desiring to Better Their Condition (1881) grew out of his position as immigration emissary to Europe. Six years later he published his best-known work, Etowah: A Romance of the Confederacy, privately printed in Atlanta. Set in the South during wartime and Reconstruction, the novel is anything but a romance. Exhibiting definite Confederate sympathies but presenting a humane vision embracing sectional reconciliation, expressing the hope of the American dream, and arguing for any number of worthy causes (from opposition to convict labor to the medical treatment of alcoholism), Etowah is curiously lifeless, closer to a series of essays than a novel. It was, however, widely and favorably reviewed, especially in the North. Fontaine published one more novel, which appeared in 1891 as Amanda, the Octoroon: A Novel (published in Atlanta by J. P. Harrison) and in 1892 as The Modern Pariah: A Story of the South (privately printed in Atlanta). In many ways more interesting and more novelistic than Etowah, it too has its share of essay-like passages, and its moral focus is ambiguous, seeming to be both an attack on racial prejudice and an endorsement of it.

Fontaine was twice married, first in 1870 to Mary Flournoy of Columbus, by whom he had two children (Francis Maury, a graduate of the University of Georgia, who died young, and Mary Flournoy). His second marriage, in 1885, to Nathalie Hamilton of Athens produced no offspring. Fontaine died on May 3, 1901, at his home in Atlanta. He is buried in the Fontaine plot in Columbus.