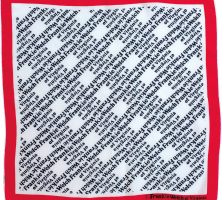

Frankie Welch was a scarf designer and fashion entrepreneur whose clients included politicians and First Ladies as well as prominent businesses, universities, and organizations. She operated a dress shop near Washington, D.C. named Frankie Welch of Virginia, from 1963 to 1990.

Early Biography

Welch was born Mary Frances Barnett on March 29, 1924, in Rome, Georgia, the youngest of four children. Her parents were Eugenia Morton and James Wyatt Barnett, who worked for Southern Bell Telephone Company. She graduated from Rome High School in 1941, then enrolled at Furman University in Greenville, South Carolina. In 1944, after her junior year of college, she married her childhood sweetheart, William Calvin “Bill” Welch, who was serving in World War II (1941-45). A few years later they returned to Furman, and Frankie graduated in 1948 with a degree in clothing and design.

After Bill graduated in 1950, the couple moved to Madison, Wisconsin, where he pursued a master’s degree in American history. Frankie took and taught sewing classes while there. She also developed a life-long admiration for the architect Frank Lloyd Wright, whose Taliesin estate and studio was nearby. Their first daughter, Peggy, was born in Wisconsin.

Frankie Welch of Virginia

In 1952 the young family moved to Alexandria, Virginia (near Washington, D.C.) for Bill to work with the federal government. Frankie soon began teaching classes and seminars about fashion, sewing, and home economics. She also offered private consultations to women seeking fashion advice and helped them create coordinated wardrobes. During this time, she developed a network of prominent women in the area. The Welches’ second daughter, Genie, was born in Alexandria.

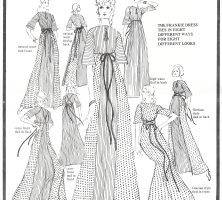

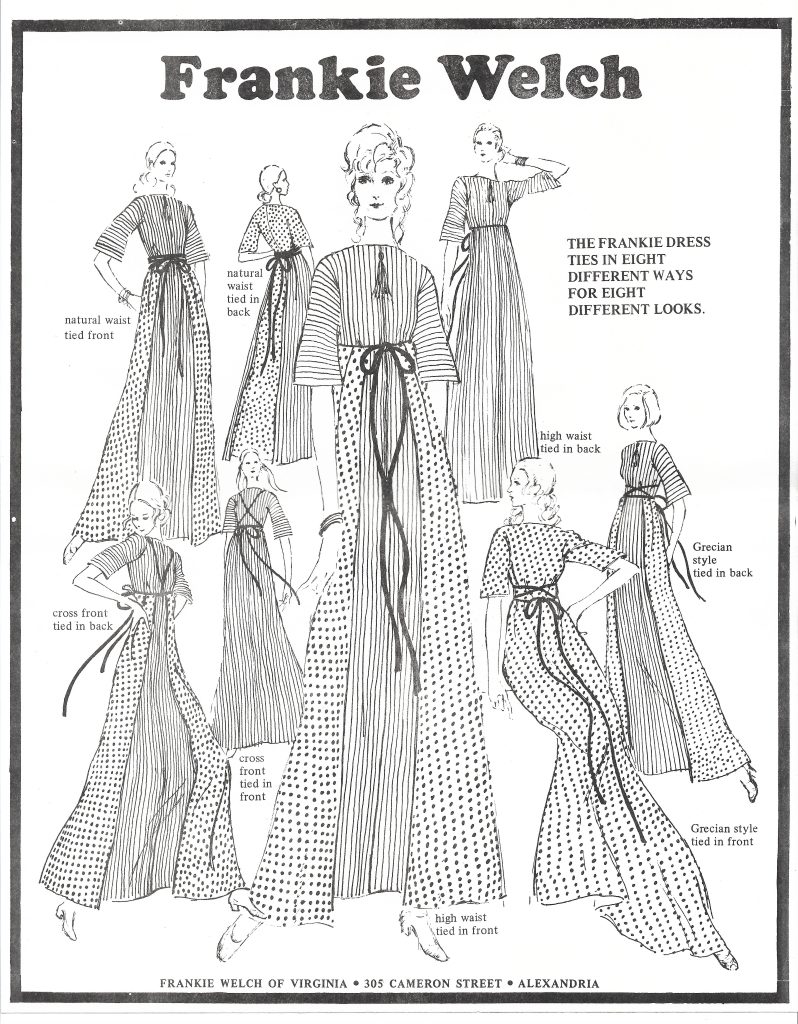

In 1963 Welch opened Frankie Welch of Virginia in Old Town Alexandria. The shop carried clothing and accessories by primarily American designers in a middle price range. She also sold some clothing of her own design, most notably her Frankie dress. Welch designed the Frankie initially as a tool for teaching students about various historic waistlines. The dress has a simple silhouette and is modeled loosely after Japanese kimonos and Claire McCardell’s popover dress. With a wide side section and long ties, the Frankie can be worn multiple ways: tied in the front or in the back, with a high waist or natural waist, crossed over the chest or not, with the zippered side in back or front. She made this popular dress in a variety of fabrics.

Early Scarves

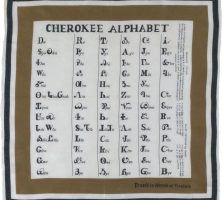

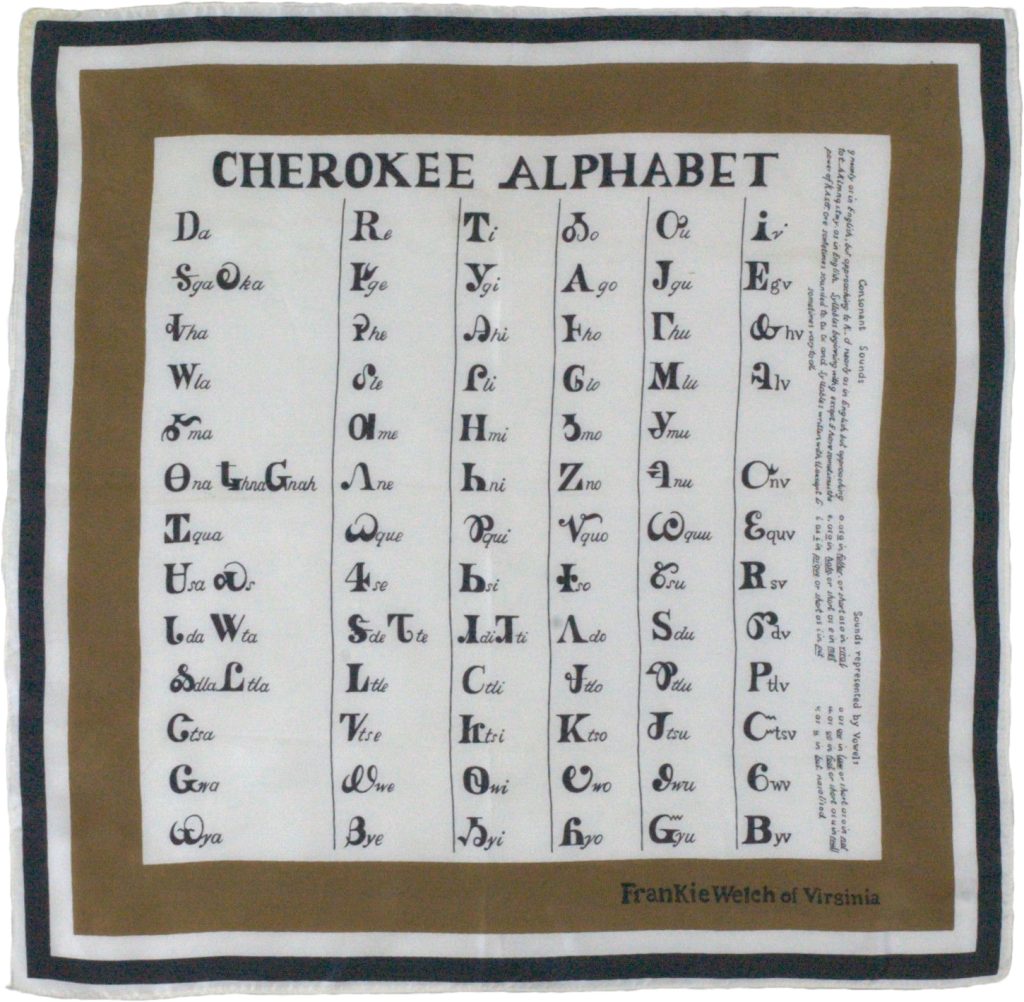

Many well-known women in the Washington, D.C., area enjoyed spending time in Welch’s shop, including Virginia Rusk, wife of Secretary of State Dean Rusk. During one visit, Rusk asked Welch to design something “truly American” that the State Department and White House could use as gifts. Inspired by a visit to her hometown of Rome where she had seen one of her father’s books with an image captioned “Cherokee Alphabet,” she designed her Cherokee Alphabet scarf. (Technically, the scarf depicts a syllabary, with the characters representing syllables rather than phonemes as in the Roman alphabet.) It was immediately successful and remained her most popular scarf throughout her career.

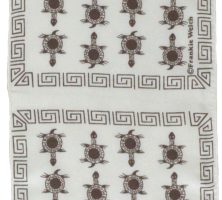

For Welch, the scarf honored her home state of Georgia and her ancestors. Based on oral family history, Welch believed that she was part Cherokee. However, current genealogical research does not support that connection. She donated money from the sale of each scarf to a Cherokee scholarship fund, and prominent women of Indigenous heritage embraced her designs. However, this scarf, and Welch’s other Native American-inspired designs, are now viewed as examples of cultural appropriation.

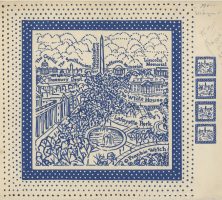

Welch’s second scarf was designed for an event in early 1968: the first fashion show to take place at the White House. Lady Bird Johnson was First Lady at the time, and the theme of the fashion show was “Discover America in Style,” which featured American designers. Welch’s red, white, and blue scarf displays the words “Discover America” over a stylized shape of the continental United States. The scarves featured prominently on the runway and were given as gifts to the attendees.

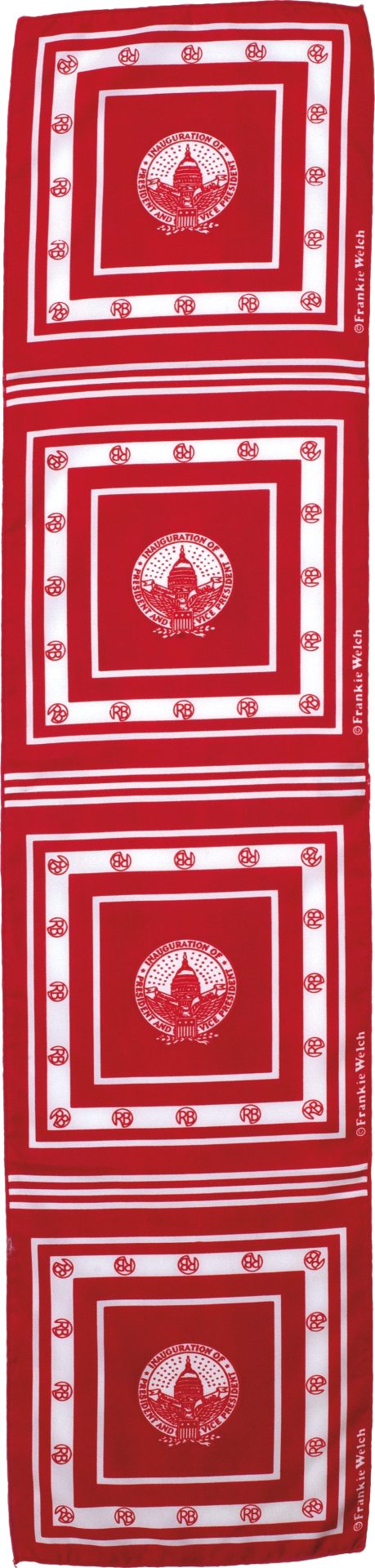

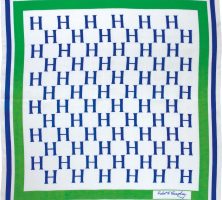

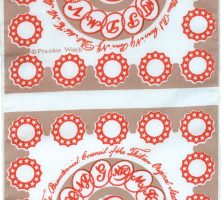

Welch created several important political designs for the 1968 presidential contest. Welch’s friend Betty Ford asked her to design a “documentary fabric” (a textile that commemorates an event or expresses political affiliations) for the Republican Party. It featured daisies with the words “Republican National Convention,” as well as the convention’s date and location. Fifty hostesses wore dresses of the fabric at the opening luncheon. Welch then designed green and blue “H-line” dresses (a play on the popular A-line silhouette) for Democratic Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey’s campaign. She also designed scarves both for Humphrey supporters and for attendees at Richard Nixon’s inaugural ball. The media noticed Welch’s ability to be bipartisan in her designing, and she enjoyed being able to say that Democrats and Republicans shopped side by side in her store.

Building a Scarf Business

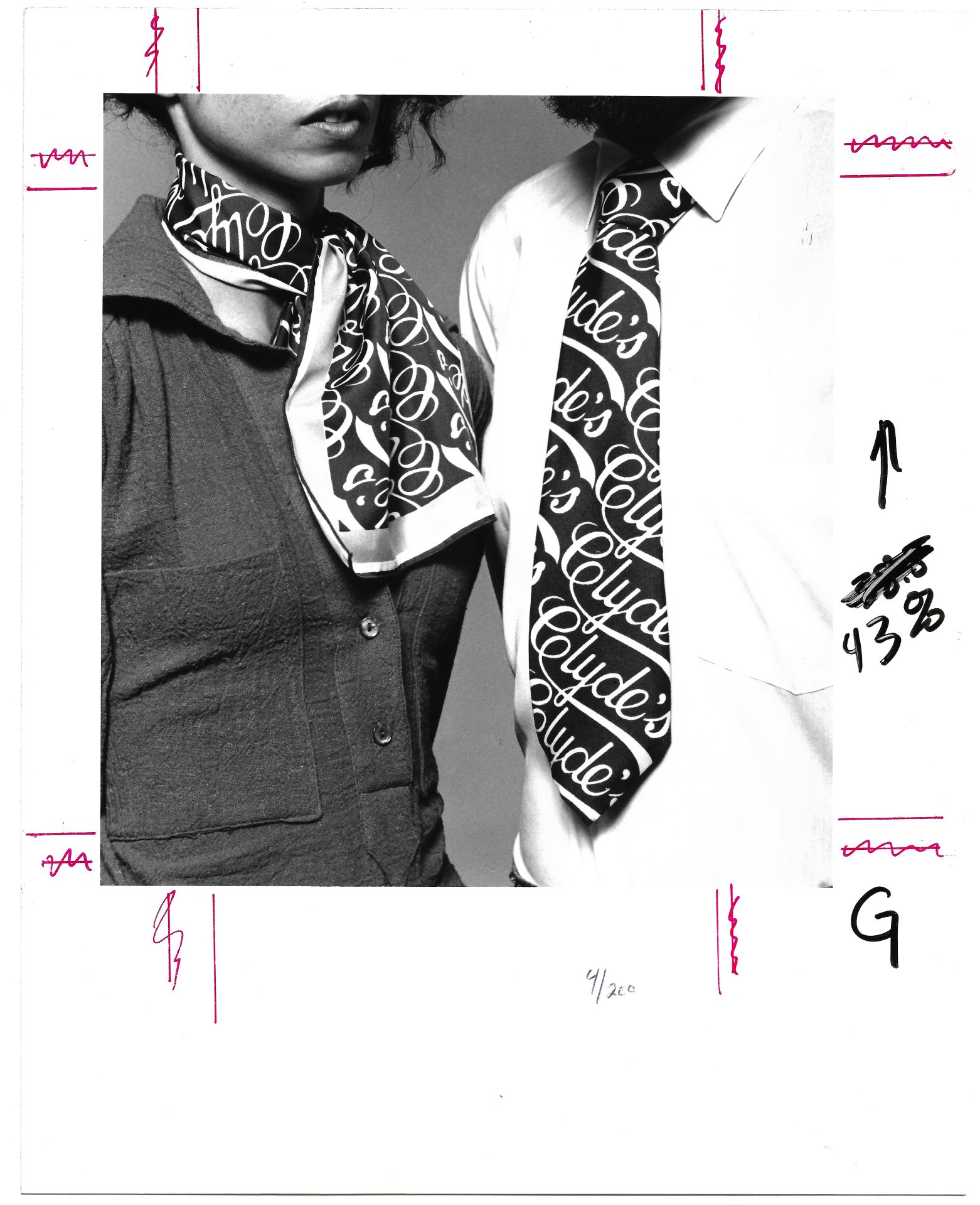

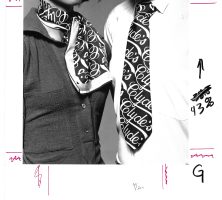

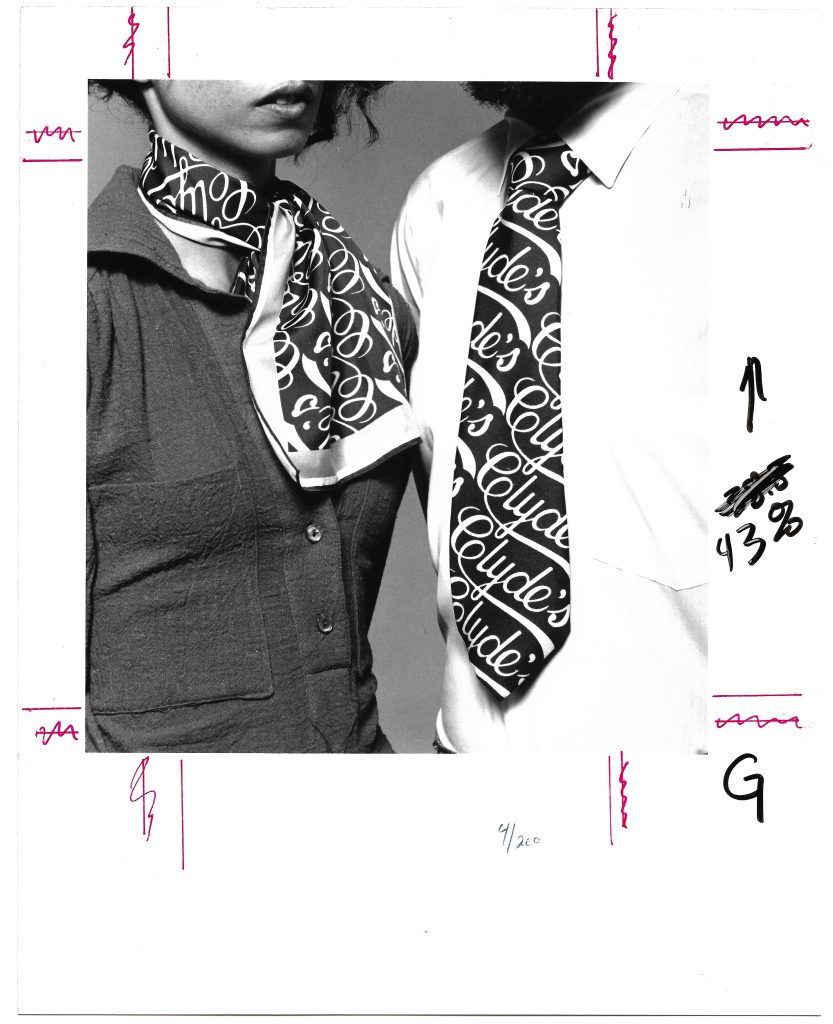

Following her success during the 1968 political season, Welch decided to expand her business. She sent promotional brochures to 5,000 large companies and institutions, offering to design custom scarves on commission. While some of her scarves were manufactured in large numbers and retailed in shops around the country, the majority were limited-edition, custom scarves for specific clients.

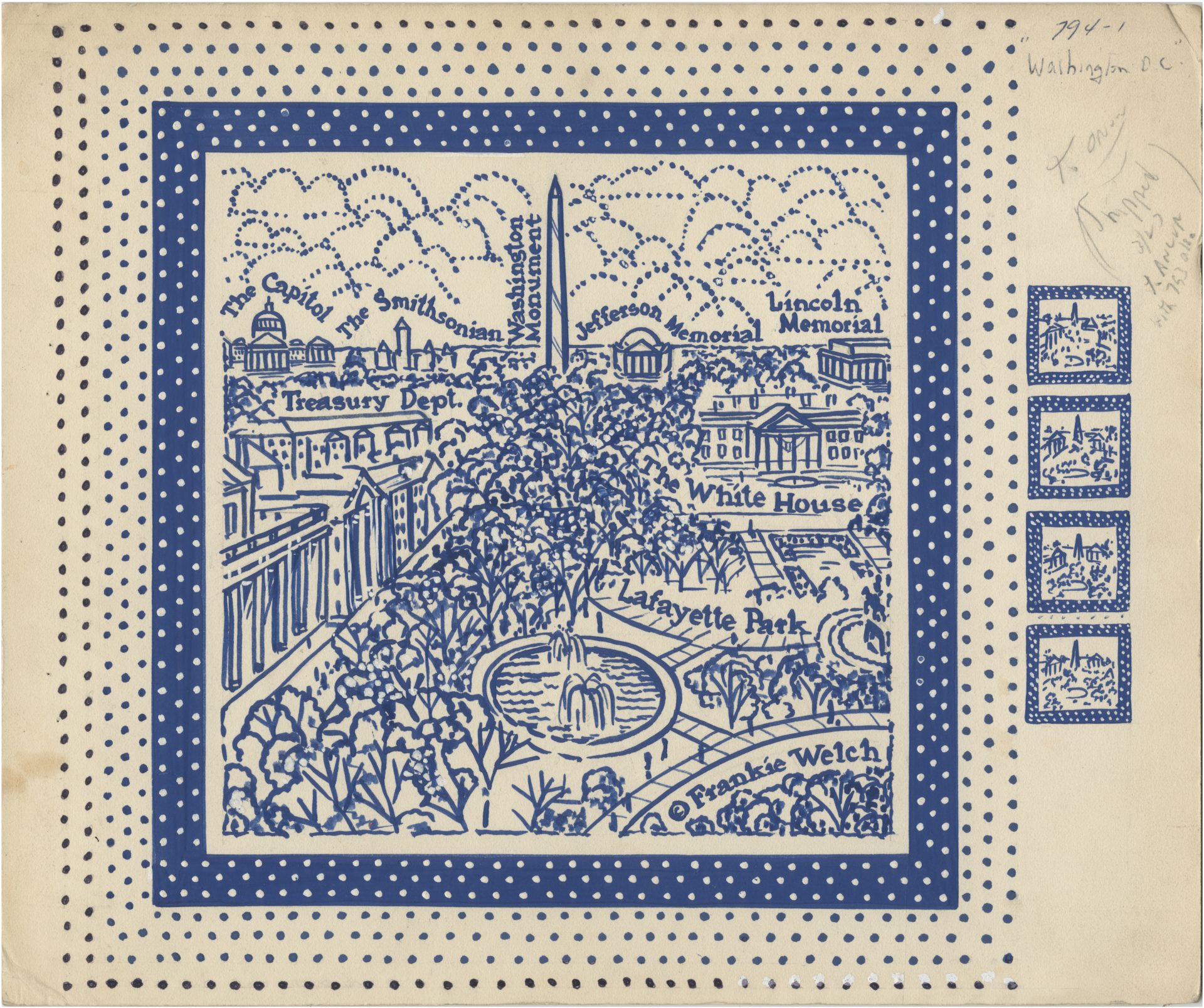

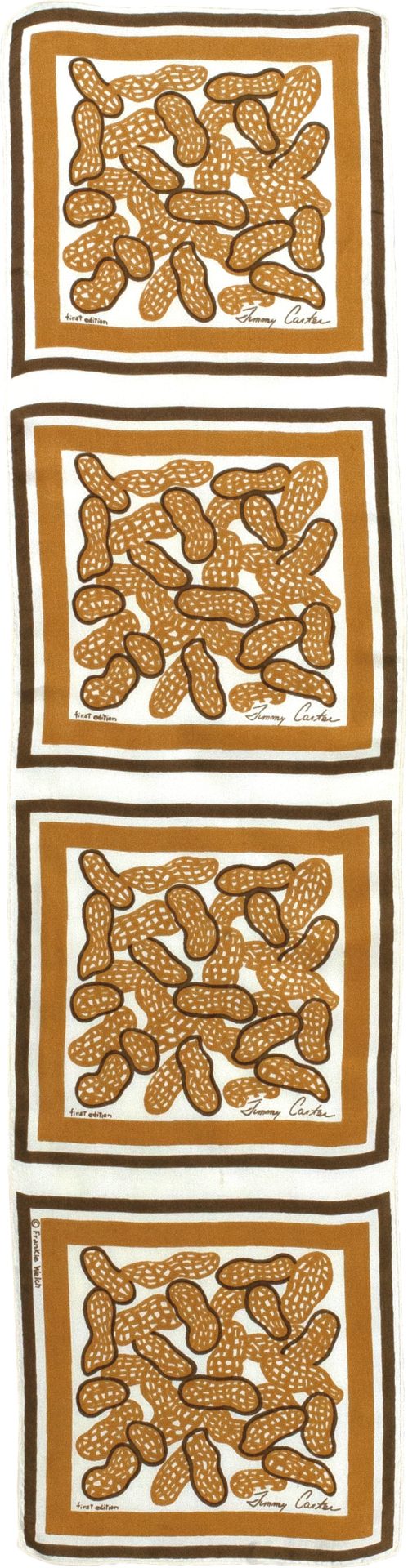

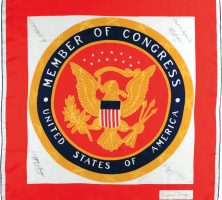

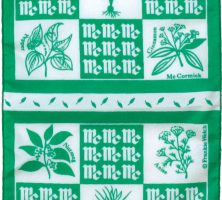

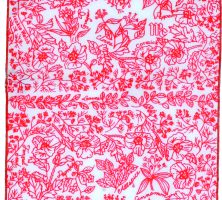

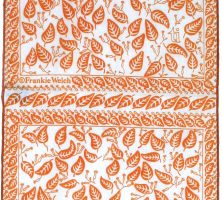

Her early scarves were primarily large squares of cotton or silk. In the 1970s and early 1980s, she favored smaller scarves, often in the popular synthetic fabrics of the era. Many of these scarves are based on 8-by-8-inch modules, an inspiration from Frank Lloyd Wright. Most scarves featured four modules in a column, though she frequently hemmed single modules and called them napachiefs, a combination of “cocktail napkin” and “handkerchief.” Her clients included McDonald’s, the Tobacco Institute, 4-H, the American Cancer Society, the Auto-Train, the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum, the Folger Shakespeare Library, the Industrial College of the Armed Forces, McCormick (spices), Monsanto, and the National Press Club. She also designed scarves for Jimmy Carter when he was governor of Georgia and for his presidential campaign.

When Betty Ford became First Lady, Welch received extensive media attention and was often described as the fashion advisor to the First Lady. Ford bought many of her clothes at Frankie Welch of Virginia and often wore scarves designed by Welch. When Ford was asked to donate a dress to the Smithsonian’s First Ladies Collection, she selected a favorite dress by Welch.

Welch closed her dress shop in 1990, though she continued to design scarves for another decade. Most of her later scarves were large silk squares or cotton bandanas. She relocated in 2001 to Charlottesville, Virginia, near one of her daughters, and died on September 2, 2021.

Frequently described as “Americana,” Welch’s designs provide a chronicle of American life, especially as she and her peers experienced it, during the later decades of the twentieth century. Her scarves constitute a unique body of work in the history of American fashion, standing apart from exclusively design- or art-based scarves because of Welch’s embrace of their commercial and documentary possibilities.