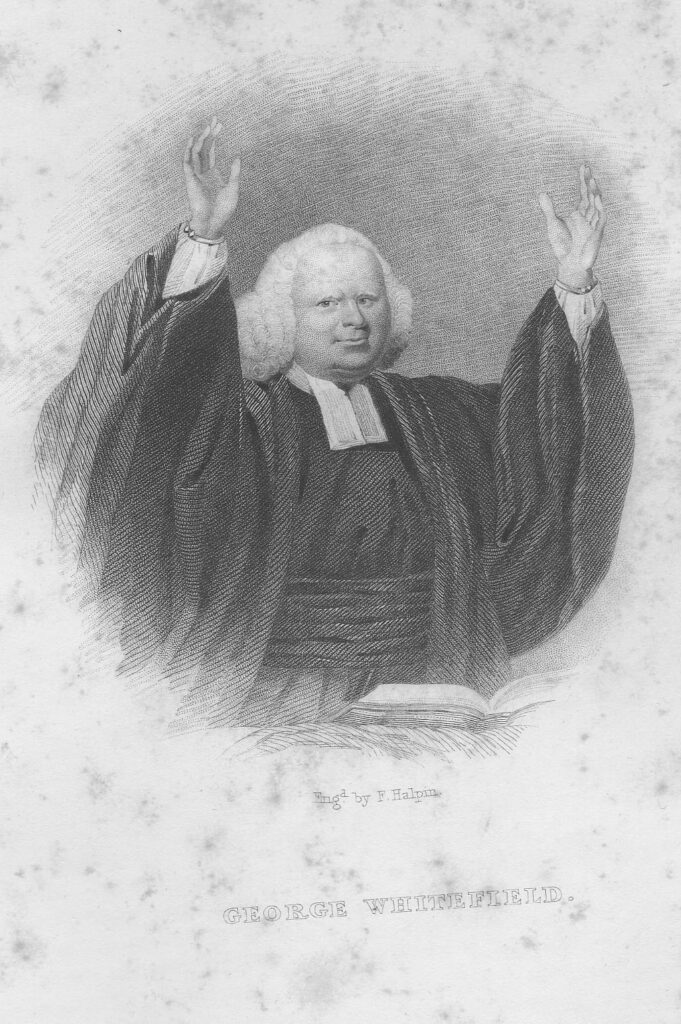

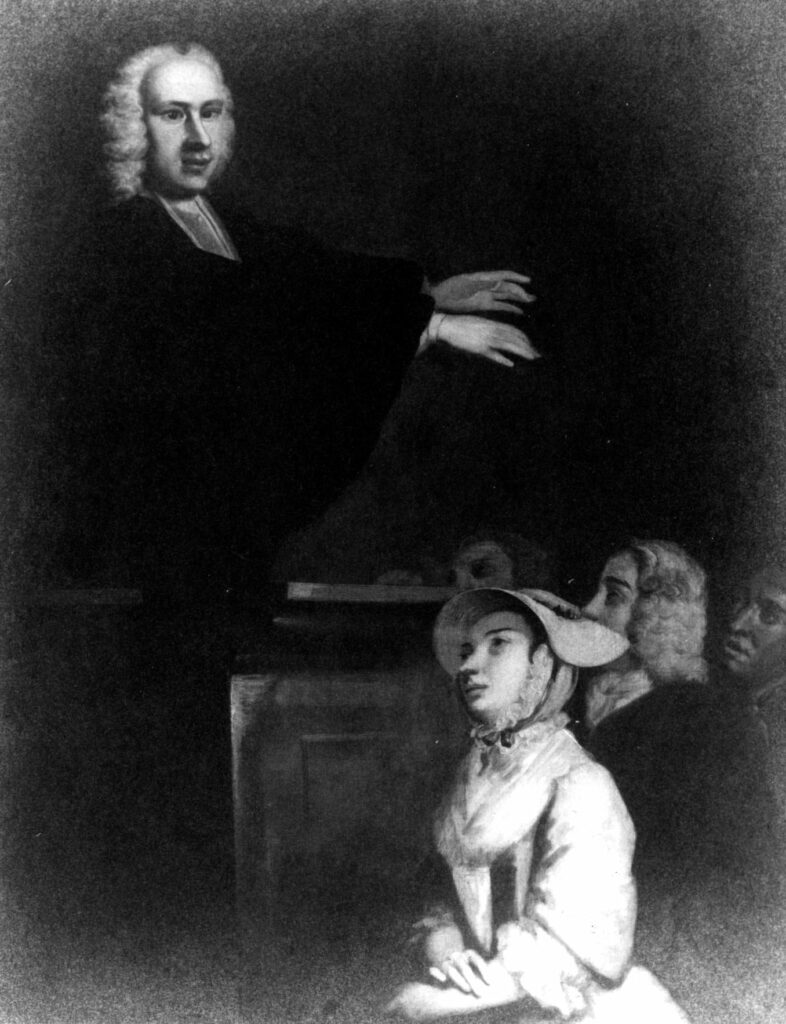

George Whitefield, together with John Wesley and Charles Wesley, founded the Methodist movement. An Anglican evangelist and the leader of Calvinistic Methodists, he was the most popular preacher of the Evangelical Revival in Great Britain and the Great Awakening in America. His unrivaled preaching ability, evangelistic fervor, and irregular methods paved the way for the Protestant multidenominational system that developed in America.

George Whitefield was born on December 16, 1714, in Gloucester, England, the seventh and youngest child of Elizabeth Edwards and Thomas Whitefield. Whitefield was educated first by his mother and then at St. Mary de Crypt school and Pembroke College, Oxford, which he entered on November 7, 1732. His association with Charles Wesley led to his participation with the Oxford Methodists, and he became the group’s leader in 1735, after Charles and John Wesley departed for America. In 1736 Whitefield was ordained deacon of the Anglican Church and earned his Bachelor of Arts degree. He spent the next year preaching in England and collecting funds for Georgia. The Wesleys had invited him to join them in Georgia, which he did in May 1738. Four months later Whitefield returned to England in order to raise money for the establishment of an orphanage near Savannah, and to secure priest’s orders, which he received in January 1739. Because of his irregular preaching methods, he found many churches closed to him, so he turned to open-air preaching.

Whitefield returned to America for the second of his seven visits in November 1739, arriving at Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. From there he traveled throughout the colonies, preaching mainly in Presbyterian churches and outdoors. He became the most visible figure of the American evangelical movement known as the Great Awakening. Arriving in Savannah in January 1740, he received a hero’s welcome. Whitefield was designated minister of Savannah by the Georgia Trustees in 1738, and his extempore preaching and praying, as well as his willingness to officiate in dissenter meeting houses, was well received in the colony. An effort by Alexander Garden, the Church of England commissary in Charleston, South Carolina, to suppress Whitefield’s irregularities failed.

Courtesy of Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries.

Upon his arrival in Savannah, Whitefield had provided approximately $2,539 toward the cost of constructing Bethesda Orphan House in the city. Back in England by March 1741, he sought more funds for the “poor orphans” of Georgia wherever he preached. His dream was to add an academy and eventually a college to Bethesda. Although an academy was eventually built at Bethesda Orphanage, Whitefield’s plan for a college was thwarted in England, despite backing from Georgia’s governor, council, and assembly.

In November 1741 Whitefield married Elizabeth Burnell James. The couple had one child, who died in infancy.

A rift between Whitefield and the Wesleys in 1741 led to his calling a conference of Calvinistic Methodists on January 5, 1743. An association was formed and a tabernacle built in the Moorfields area of London. The Calvinist teaching of predestination grace and divine initiative broke from the Wesleys’ emphasis on free grace and free will. While both parties believed in such doctrines as original sin, justification by faith, the substitution atonement, and sanctification, they differed in their understanding of the human role in the process of salvation.

A similar debate also occurred in America among evangelicals in the generation prior to the Revolutionary War (1775-83), when colonists were asserting their natural right of self-determination against British imperalism. The claim for human agency in religion alongside the assertion of self-determination in civil affairs strengthened the call for “human choice” and the “voluntary principle,” which both became prominient features of American life.

In 1749 Whitefield became a chaplain to Selina, Countess of Huntingdon, a founder of the Calvinistic Methodists and the trustee of Bethesda upon Whitefield’s death. He died on Sunday, September 30, 1770, in Newburyport, Massachusetts, and is buried there beneath the pulpit of First Presbyterian Church.