Beginning in 1883, several young women from Georgia astonished the nation by demonstrating strange powers in their vaudeville acts. For years afterward, they were among the most popular and controversial variety performers in America and Europe. Two of these women, Lulu Hurst and Annie Abbott, were particularly successful.

Lulu Hurst

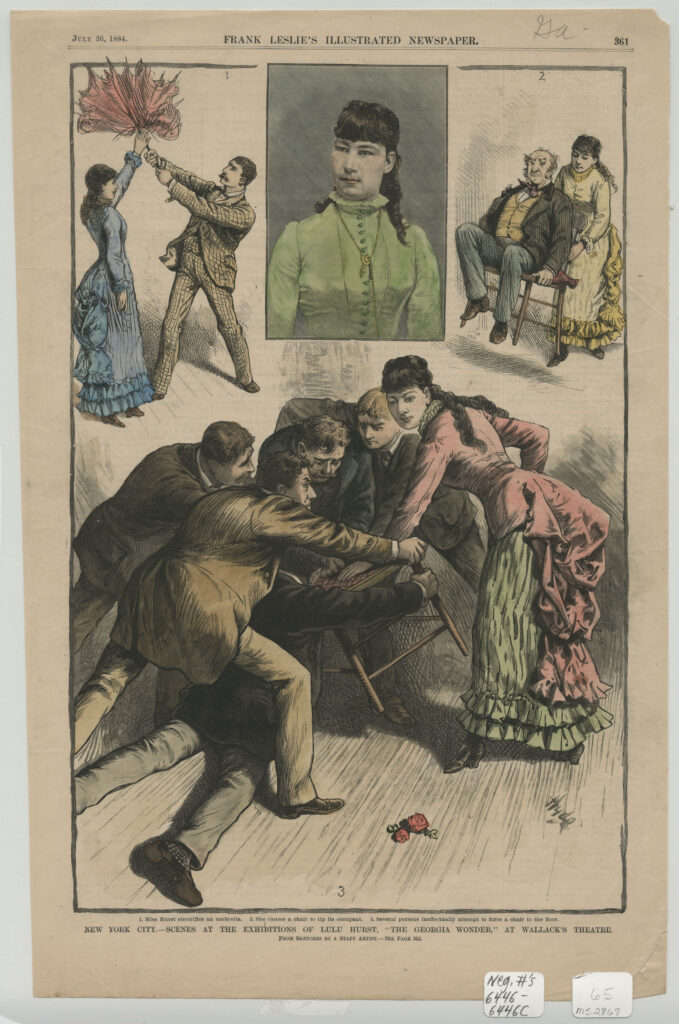

Lulu Hurst, the first Georgia Wonder, was born in 1869 in Polk County. In September 1883 she gained local attention by demonstrating mysterious abilities: chairs, canes, and umbrellas, held by others, seemed gripped by an invisible power when Hurst touched them lightly.

In one of her demonstrations, a volunteer, usually a man of considerable strength, held a cane horizontally in both hands. When Hurst placed her open hands on the cane, the man could no longer hold it steady. Holding it became as difficult as “trying to hold down a flash of lightning,” as one volunteer put it. In some cases the volunteer himself was pulled about by a mysterious power and even thrown to the floor. With such demonstrations, and the help of theatrical manager Sanford H. Cohen and newspaper editor Henry Grady, Hurst’s vaudeville act was soon in demand throughout Georgia and beyond.

Hurst and her parents toured the South and Northeast in 1884, and the West and Midwest in 1884-85. By the conclusion of her northeastern tour, including highly successful appearances in Boston, New York, and Washington, D.C., Hurst, just fifteen, was one of the most famous women in the country. In her western tour, however, Hurst found audiences increasingly uncooperative, as other women duplicated her act and observers explained her feats. In fall 1885 Hurst cancelled a tour of Europe, retired from the stage, and retreated into silence.

Courtesy of Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries.

Hurst refused to discuss her career or her powers until 1897, when she published a best-selling autobiography that gave a selective account of her tours and an explanation of her methods. She then resumed her silence about her theatrical years and maintained it to her death on May 13, 1950.

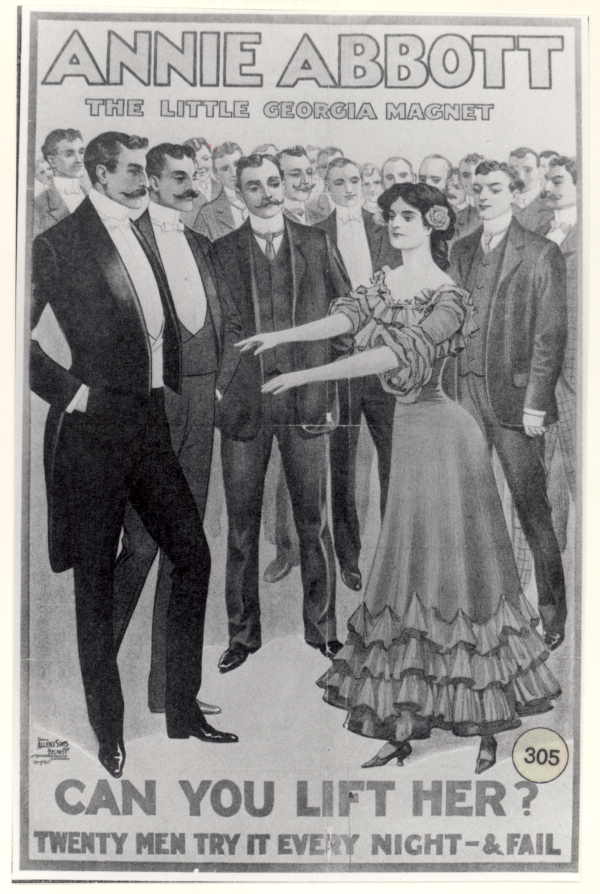

Hurst’s fame and substantial earnings inspired many imitators, including Mattie Lee Price of Bartow County and Mamie Simpson of Marietta, but the most successful was known as “Annie Abbott, the Little Georgia Magnet.”

Annie Abbott

This performer, born Dixie Annie Jarratt in 1861, married Charles N. Haygood when she was seventeen. The couple apparently witnessed Hurst’s performances in Milledgeville in 1884 and February 1885, and Dixie Haygood first performed her version of Hurst’s act publicly in early March 1885. She soon adopted the stage name Annie Abbott.

After her husband’s death in 1886, Abbott supported herself and her children by gradually expanding her tours to include northern cities. In 1891 a successful run in New York City led to performances in London, England. She was enormously successful there, performing at the Alhambra Theatre before packed houses for six weeks. She then toured Europe and Russia for nearly two years, literally performing, in the old theatrical phrase, “before all the crowned heads of Europe.”

Her success was in part due to her creation of new and remarkable effects, including the apparent ability to resist being lifted from the floor by male strength and thereby to defy physics (hence her nickname, the “Georgia Magnet”). Abbott’s performances were also more impressive than Hurst’s because Abbott was a smaller woman, a petite 100 pounds, and clearly unable to achieve her effects by weight or physical strength.

Like Hurst, Abbott was frequently examined by physicians and others, who were usually baffled by her feats. Newspapers often revealed her methods (which, like Hurst’s, employed the clever and practiced use of leverage and center of gravity, along with the power of suggestion), but Abbott continued performing. Her popularity was undiminished, perhaps because the controversy generated by the exposes drew larger audiences.

She was imitated by many; some even used her stage name, both during her lifetime and afterward, thus clouding the history of the real Abbott. She died on November 21, 1915, and is buried in Memory Hill Cemetery in Milledgeville.

Controversy followed these Georgia Wonders for decades, in part because their demonstrations raised questions about both the paranormal and women’s abilities and roles, two prominent cultural debates of the late nineteenth century.