The Reverend Howard Finster emerged from the rural Appalachian culture of northeast Alabama and northwest Georgia to become one of America’s most important creative personalities in the last quarter of the twentieth century. He was a visionary artist in various visual media as well as a poet and a musician, and his creative output and cultural influence were enormous. Although he has been called “the Picasso of folk artists,” his fusion of tradition and innovation makes the label “folk artist” insufficient. He called himself a “stranger from another world” and a “man of visions,” and described his brain as being “beyond the light of sun.”

Finster was not unique as a self-taught environmental and visual artist: many significant individuals in the South and beyond have created distinctive and inspired artworks and environments. Yet well before his death he had produced a highly personal body of work, including thousands of paintings, sculptures, drawings, and prints; and recorded and written narratives and musical material—original songs and folk-style improvisations on homemade tapes as well as commercial LP and CD issues. He had been included in hundreds of exhibitions, including the Venice Biennale in 1984 and a major exhibit at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta in 1996. He had also interacted and collaborated with artists, rock musicians, students, and teachers. His bibliography includes two major monographs, autobiographical books, and recordings, as well as hundreds of articles and entries in exhibition catalogs.

Three of Finster’s pieces are part of Georgia’s State Art Collection: the mixed media works Angel #700.033 (1987) and Visions of Other Worlds in Outer Space Beyond #13,000.494 (1989); and the enamel painting In Visions of Another World—September 15, 1990 (1990).

Formative Influences

Born in 1915 or 1916 in Valley Head, Alabama, Finster grew up in a family of thirteen children. He was nurtured in a rural Baptist background, in long-standing traditions of storytelling, humor, and music making, and in an approach to art and objects that was shaped by make-do craftsmanship, popular religious illustration, and idiosyncratic roadside attractions. His background suggests that his genius did not spring mysteriously from his inner being or from received visions (although he argued the contrary), but at least in significant measure from cultural traditions.

Steeped in rural Baptist religion and shape-note singing, Finster recalled among his formative experiences having a vision of his dead sister when he was three years old, being saved at a revival in 1929, and hearing a call to be a preacher in 1931. With his wife of two years, Pauline, and their first child, he moved in 1937 to Chattooga County, where he spent the rest of his life. In the 1940s, as his family grew, he worked in the cotton mills in the town of Trion, preached revivals in the area, and eventually began to pastor the first of several Baptist churches he served until his retirement from formal ministry in 1965. In the late 1940s and early 1950s he constructed his first “park,” mainly to fulfill his creative urges and please his family and community. This outdoor museum at his home in Trion featured small replicas of churches and heavenly “mansions.”

Pennville

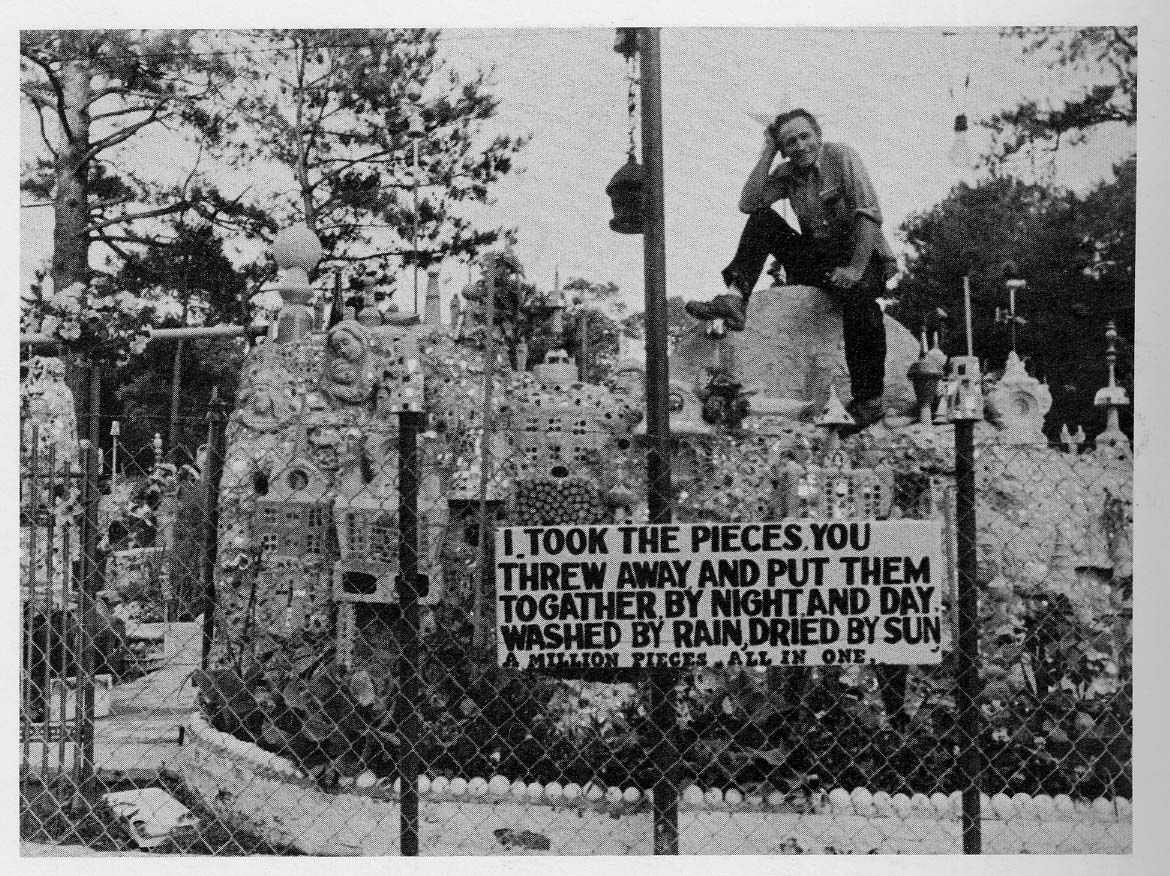

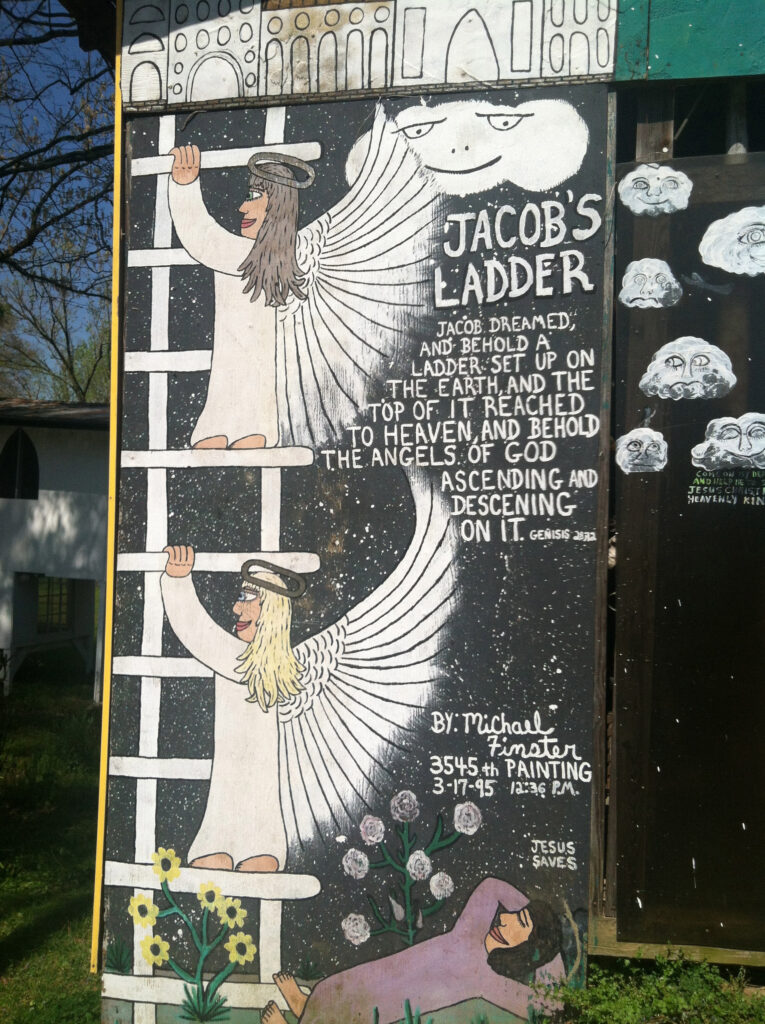

In 1961 the Finsters moved to Pennville, between Trion and Summerville, where he worked at bicycle and small-engine repair and at woodcraft. At this time, in response to a mystical vision, Finster began filling a marshy area behind his house and undertook the construction of what he called his “Plant Farm Museum,” which eventually contained plywood and concrete sculptures; walls, buildings, and trellises festooned with “every man-made item”; didactic, humorous, and religious texts and homilies; biblical signs and paintings; canals and ponds; and two towers made of bicycle and lawnmower frames. This work first received national attention in a 1975 Esquire magazine article on self-taught artists, in which it was renamed “Paradise Garden.” The following year, as Finster was retouching a bicycle paint job, he saw a face in a dab of paint on his fingertip, which he repeatedly said he understood to be a call to “paint sacred art.” He began the series of what became thousands of numbered paintings, some of which were included in the 1976 exhibition, Missing Pieces: Georgia Folk Art, 1770-1976, that launched his career as an exhibiting artist.

National Recognition

After what he termed “the publicity part of it” started, Finster welcomed an ever-increasing stream of visitors to the ongoing art project. Art professors like Andy Nasisse from the University of Georgia and Victor Faccinto from Wake Forest University in North Carolina began encouraging Finster to visit art schools and universities to lecture and to do “workouts” (collaborative art projects) with students. Allan Jabbour, director of the American Folklife Center of the Library of Congress, commissioned major paintings for that institution, and the art dealer Jeffrey Camp and, later, gallery owner Phyllis Kind began promoting and marketing Finster’s work. In 1982, with partial help from a National Endowment for the Arts grant, he purchased a small church adjacent to the garden, which he expanded into a wedding-cake-like structure he called the “World’s Folk Art Church.” In the same year he began his collaboration in video and album design projects with the Athens-based rock group R.E.M.

In 1983 Finster appeared on Johnny Carson’s Tonight show on NBC, where he resisted Carson’s attempt to draw chuckles from the audience by having him describe the oddities of Paradise Garden. Finster literally took over the show, playing his banjo and singing humorous didactic songs. Though he was already appreciated in the academic and art worlds, the Tonight show appearance signaled Finster’s entrance into mainstream American culture; from that time many of his family members began helping him in his endeavors and producing spin-off “Finster” art of their own. Gradually his hometown community moved from viewing him as a local eccentric to counting him as a community asset and instituting a “Howard Finster Day” folk art festival.

Finster’s most original and powerful contributions to art were his garden, the sculptural and architectural works within it such as his bicycle frame constructions and the World’s Folk Art Church, and his significant paintings of the 1970s and early 1980s. These latter works, rich in formal and poetic invention, are apocalyptic visions laced with humor and personal and universal imagery.

The Final Years

In the last fifteen years of his life Finster continued to be featured in numerous exhibitions, the most important being his retrospective at the High Museum of Art. As his health declined he continued to make art, although the forms and images became more repetitious and less inventive. He and Pauline moved away from the Paradise Garden to a home in Summerville but returned regularly to the gallery/visitors’ center that his family maintained, where he greeted visitors with banjo playing and songs and impromptu sermons and monologues.

When he died in 2001 the garden was being maintained by his family and supporters, while important three-dimensional works, as well as paintings, had been placed in collections and museums. The High Museum created a permanent installation of Finster’s art.

By the end of the decade, Paradise Garden, including the chapel, had fallen into serious disrepair. Restoration efforts began around 2010, and in early 2012 Chattooga County purchased the property. The newly formed Paradise Garden Foundation, meanwhile, assumed management responsibility. In April the garden was listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and in June the property received two major grants to aid in restoration—$445,000 from ArtPlace America and $225,000 from the Educational Foundation of America.

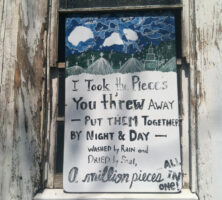

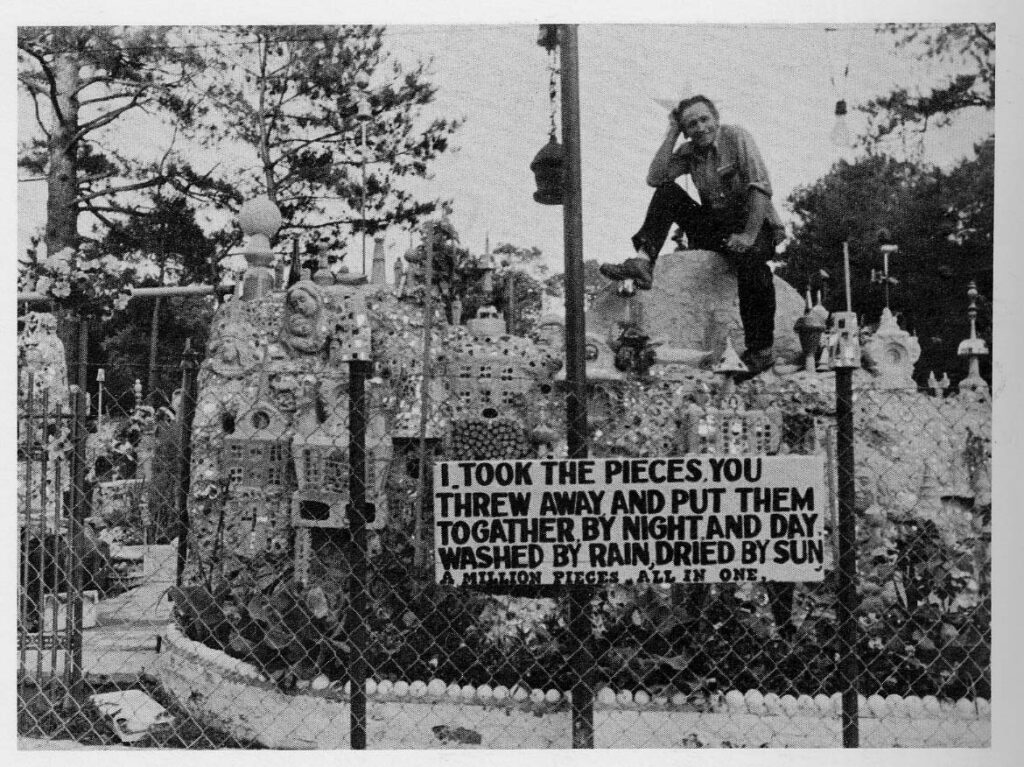

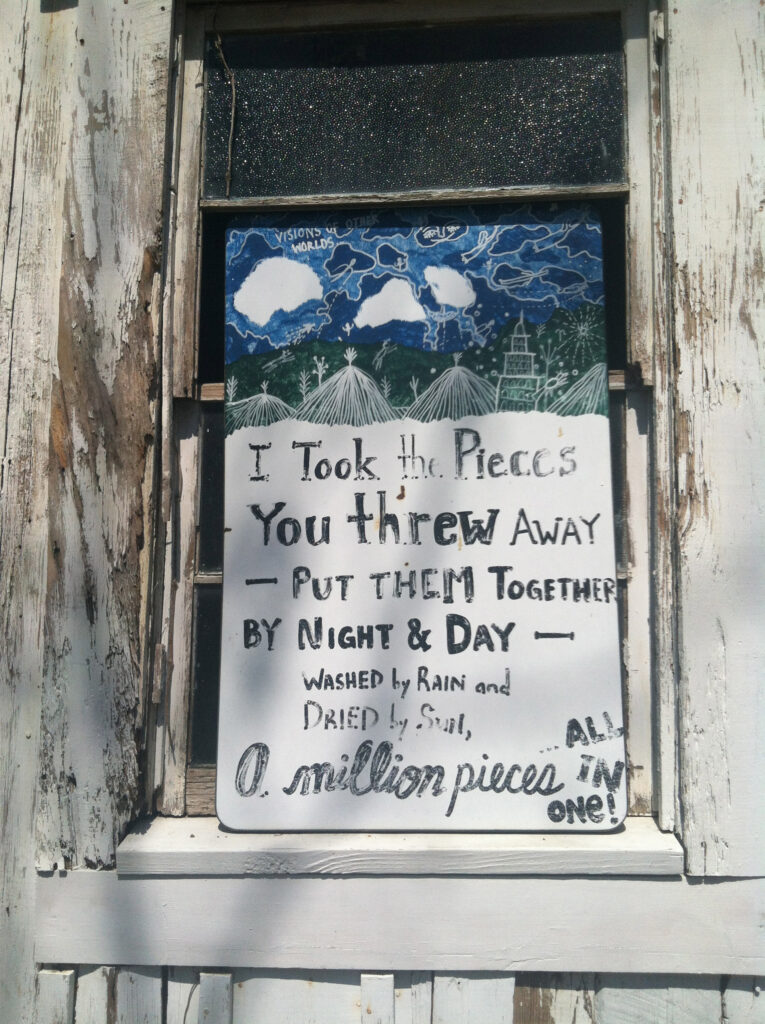

Howard Finster is recognized today as a major artist, rather than an interesting eccentric belonging to some hard-to-define subcategory of “outsider” or “folk” art. He ultimately forged an important body of work that lives up to the most frequently quoted inscription from his garden:

I TOOK THE PIECES YOU THREW AWAY

PUT THEM TOGETHER BY NIGHT AND DAY

WASHED BY RAIN AND DRIED BY SUN

A MILLION PIECES ALL IN ONE.