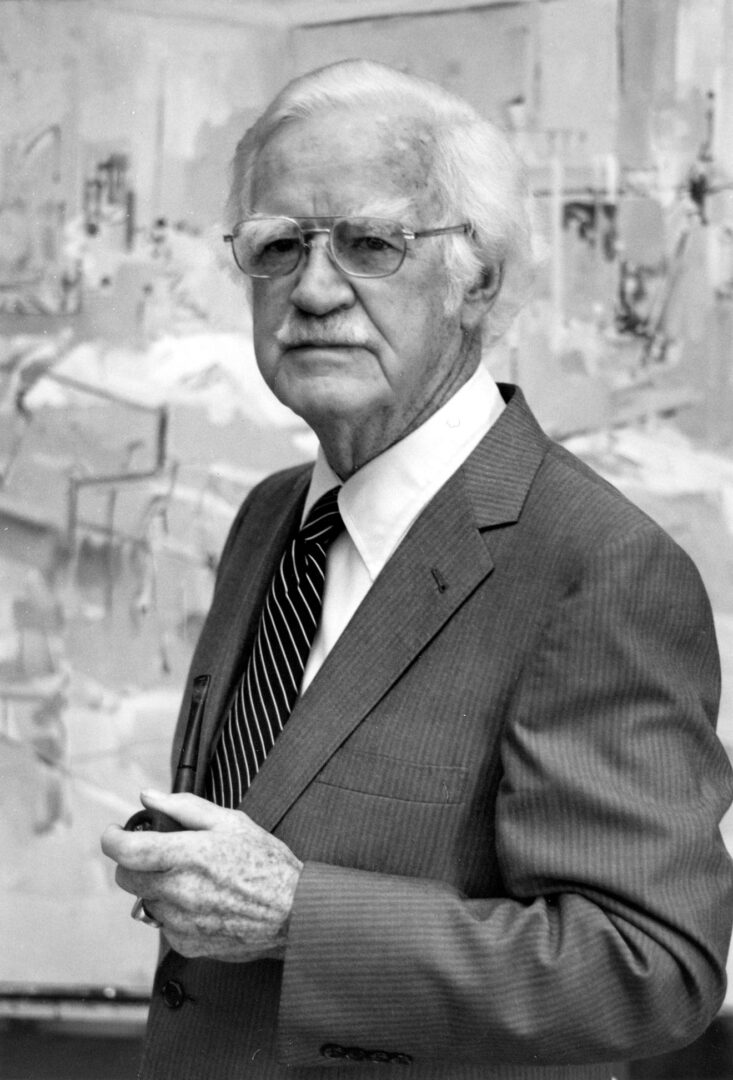

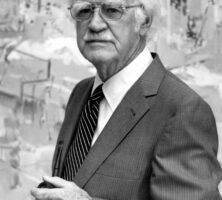

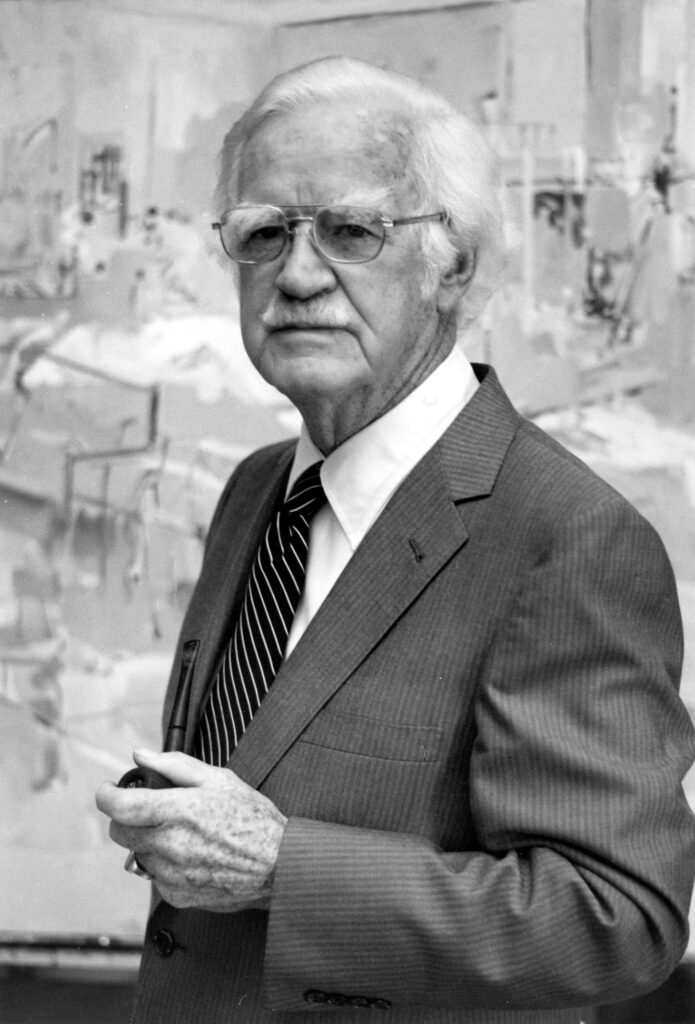

Lamar Dodd was not only the most recognized artist of his generation from the state of Georgia but also a passionate advocate for the arts and a skilled administrator. His most visible legacy is the Lamar Dodd School of Art at the University of Georgia.

Courtesy of LaGrange College

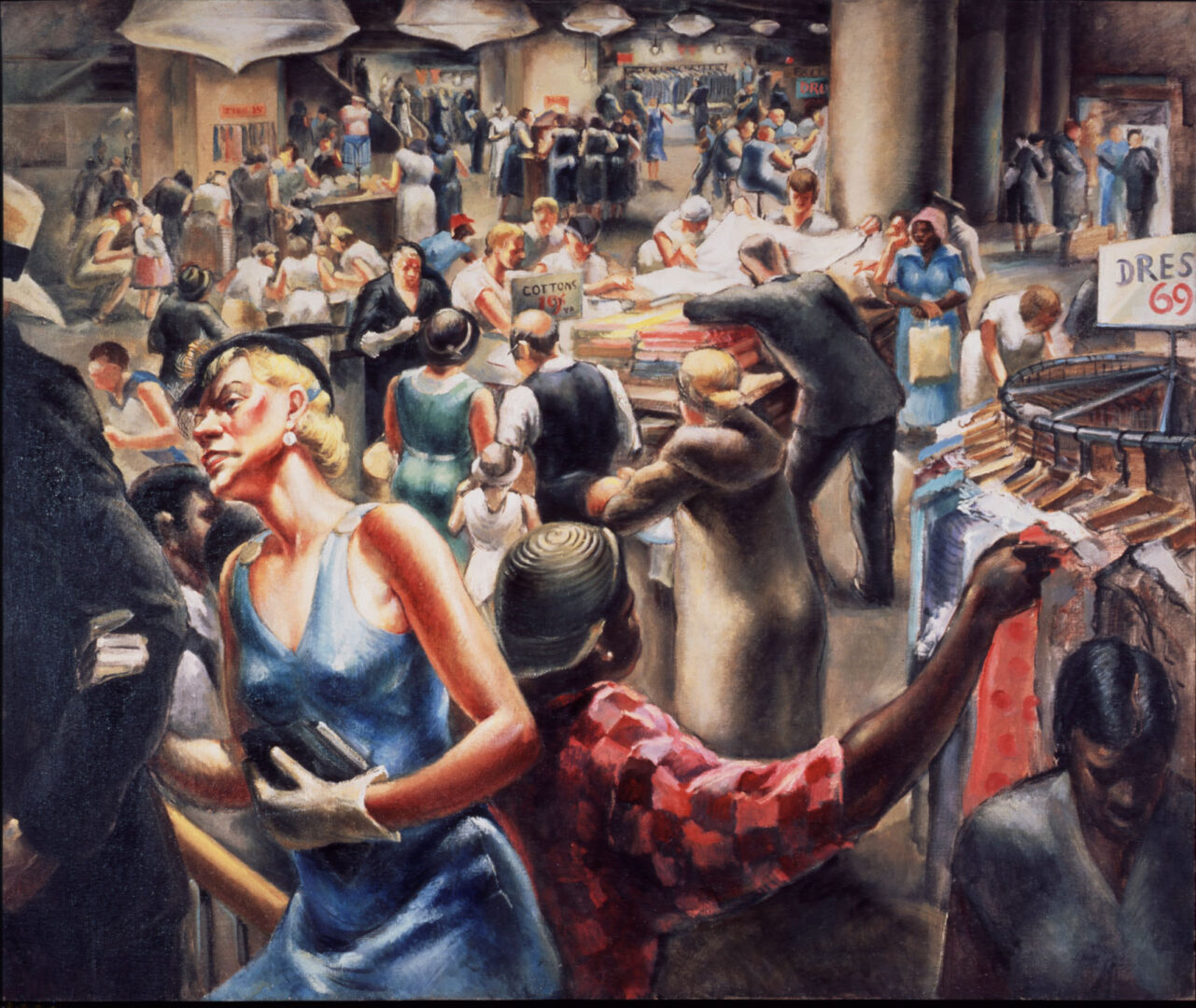

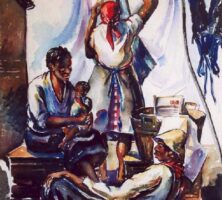

Born on September 22, 1909, in Fairburn and reared in LaGrange, Dodd took classes at LaGrange Female College (later LaGrange College) when he was twelve years old. After a brief stay at the Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta, he taught art in rural Alabama, only to realize that he had to leave the South to advance his training. He enrolled at the Art Students League in New York City, where his primary teachers were Boardman Robinson and Richard Lahey. He also took private classes from George Luks, an artist associated with the Ashcan School, a movement in painting, printmaking, and illustration in New York during the 1900s and 1910s. Influenced by the Ashcan School’s emphasis on everyday scenes of urban life painted in a somber palette, Dodd equally absorbed the teachings of John Steuart Curry and Thomas Hart Benton, American Scene artists who preached a gospel of nativist art in the 1920s and 1930s.

This amalgam characterized his style when he returned south to Birmingham, Alabama, in 1933 to work in an artists’ supply store. To anyone who would listen, he championed a “local art,” one that featured southern scenes, southern history, and southern people. As one reviewer remarked of his first solo show in New York in 1932, Dodd’s paintings, one after another, all so consciously anti-academic, evoke “Georgia, Georgia, Georgia.”

As part of a national movement to put working artists into universities, Dodd was appointed to the faculty of the University of Georgia in 1937. Within three years he had consolidated all teaching of the visual arts into one department and had even enrolled the first graduate students in a master’s program. The department grew quickly and, thanks to his efforts, is today one of the largest, most comprehensive art schools in the United States.

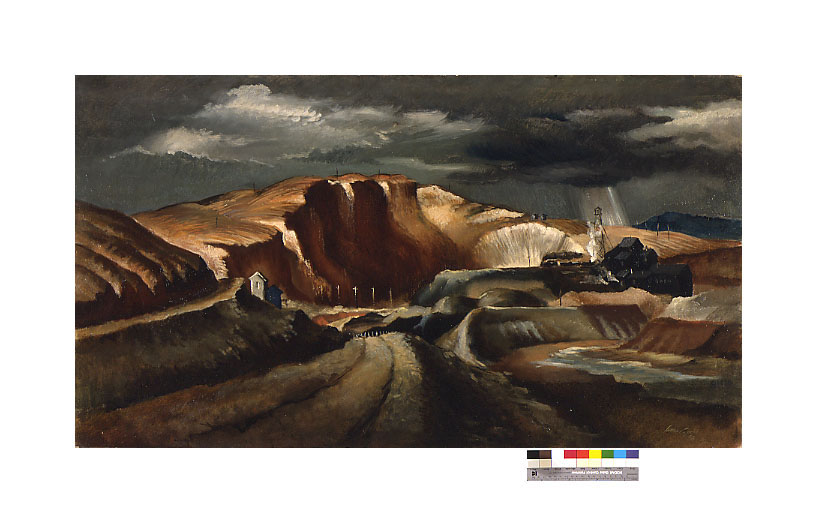

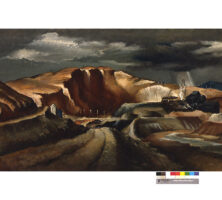

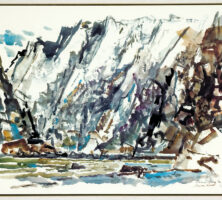

In the 1940s Dodd continued to paint the local scene, but he also began to expand that territory to include the north Georgia mountains and South Carolina’s coast and islands. Later in the decade he discovered Monhegan Island, off the coast of Maine, whose grassy shore and picturesque village had inspired artists since the nineteenth century.

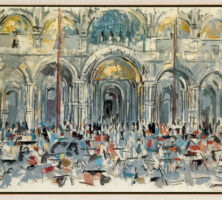

In the 1950s Dodd began to travel all over the world, first to Europe to study the old masters as well as his more immediate nineteenth-century predecessors, including Paul Cézanne, and later as a cultural emissary for the State Department to the Soviet Union, the Middle East, and Asia. Consequently his palette became brighter, and his brushstroke and technique adapted to the spreading influence of the abstract expressionists.

The next two decades saw the creation of two definitive series in which the subjective realism, the cubist tendencies, and the near abstraction of his earlier career combined to serve the purposes of depicting what would appear to be total opposites, the vastness of the cosmos and the small but vital universe of the surgical amphitheater.

Courtesy of Lamar Dodd Art Center, LaGrange College

Invited by NASA to document humanity’s conquest of space, Dodd in 1963 began work on a series of paintings that required him to adopt a vivid, expressionistic style. The symbols of moon and sun are no longer dreamy metaphors but acquire a strong presence through the heavy application of paint, or impasto. The horizon becomes curved as if viewed from above rather than from on the ground. Shiny pigments in layers of gold and silver leaf call attention to the flatness of these canvases, to their tactile surfaces. They glow and glimmer and are highly reflective. Dodd suggested a type of story, at least a symbolic one, by paneling some of these works into triptychs (three side-by-side panels), the central one always the most important in these cosmic scenes. In some, Dodd rejected colors in favor of Blacks and whites, the former for the void of space, the latter for the lunar glare or extraterrestrial light. In others the gold and silver leaf bring immediately to mind Renaissance artists and their own otherworldly, intellectual preoccupations.

In the late 1970s Dodd used similar means to investigate another, more intimate universe—that of the human heart. Again, many of the paintings are segmented so that echograms, x-rays, or microscopic studies of tissue are relegated to the periphery of the central subject, heart surgery, for which they are in service. The detailed drawings for these paintings allowed him to block out his canvases into zones of activity. Again he used, sparingly, gold and silver for their symbolic value; in some the “frame” becomes a headboard in abstract relief where “readings” of heart function or catheterization can be deciphered. It is no accident that many of the Heart series are cruciform or circular; again shape is symbolic, elemental, and linked to the “life” of the subject: rebirth through cure.

Courtesy of LaGrange College

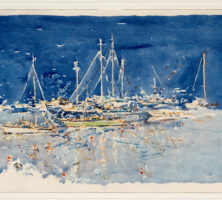

In the 1980s and early 1990s, Dodd returned to the natural world for his subjects. The seascapes of Monhegan Island in Maine were a favorite subject, as were the sunflowers of America and Europe. Usually in watercolor, these works are buoyant in mood and betray the optimism of an artist who continued to marvel at the intricate mystery of the everyday. His artistic vocabulary had become again the crisp stroke, the short burst of paint that erupted from white space: “sparks of color” that radiated from the skier’s foot, from the wave’s splash against stone, or from the glistening dew on a petal. Dodd was again urging his viewer, his student, to look closely, to join him in acknowledging the pull of the center, the essential in nature. He went full circle, from analysis of his own backyard to a study of the cosmic forces that defined all of us and, finally, back to a private, personalized universe where he asked his viewer to join him in an appreciation of the nearness of beauty.

Before his death in 1996 Dodd went back to his roots in the American Scene movement, but this time, tempered by the late-century’s emphasis on the relevant, the social, and the violent, he tackled such subjects as the bloody glove from O. J. Simpson’s murder trial (1995). Six of his works—St. Mark’s Cathedral (1956), Venice Reflection, Rain (1958), Rocks in Nature’s Garden (1963), San Marco, Rain (1972), Anchored Boats (1989), and Gunnison’s Gorge—are included in Georgia’s State Art Collection.

For fully two-thirds of the twentieth century, Dodd represented Georgia’s visual arts community as administrator, teacher, and advocate, and as the most influential Georgia artist of his generation.