Quilt making is the process of sewing decorative bed covers from layers of fabric, either for personal use or for sale. Georgia quilts and their designs have changed over time, reflecting the influences of geography, historical events, technological innovations, economic circumstances, ethnic traditions, and personal aesthetics.

Eighteenth Century

The earliest settlers in Georgia depended on transoceanic trade for their household goods. Bed covers were among the most common household textiles in the American colonies. As quilts became popular in western Europe during the late eighteenth century, they also appeared in Georgia. Only wealthy families could afford the expensive fabrics used for quilts. Among the earliest styles were whole-cloth quilts, made from two large sheets of silk or cotton fabric with a layer of loose cotton between, typically sewn together with a decorative pattern of stitches.

Early Georgia quilts were also made from printed cotton fabrics imported from India or Europe. Quilt makers cut out individual floral motifs from printed chintz fabrics and sewed them to a plain foundation in pleasing arrangements. Early chintz quilts in Georgia follow the European style, typically featuring a large central motif surrounded by multiple borders. Another European needlework technique that was popular in Savannah in the early nineteenth century was English-template piecing, or mosaic patchwork. In this technique, small geometric shapes—often hexagons—are cut from paper and covered with fabric; then the covered motifs are sewn together to form a design. Many fine early-nineteenth-century chintz and mosaic patchwork quilts survive from coastal Georgia.

Nineteenth Century

During the first half of the nineteenth century, distinctly American styles of patchwork quilts developed in the Delaware Valley. Combining British needlework techniques with German decorative traditions, these quilts featured bold geometric designs in contrasting colors. Quilt makers typically constructed their quilts with repeating blocks rather than in the older framed-center style. The new styles entered Georgia through coastal cities and inland routes into the backcountry, largely replacing older styles by about 1850.

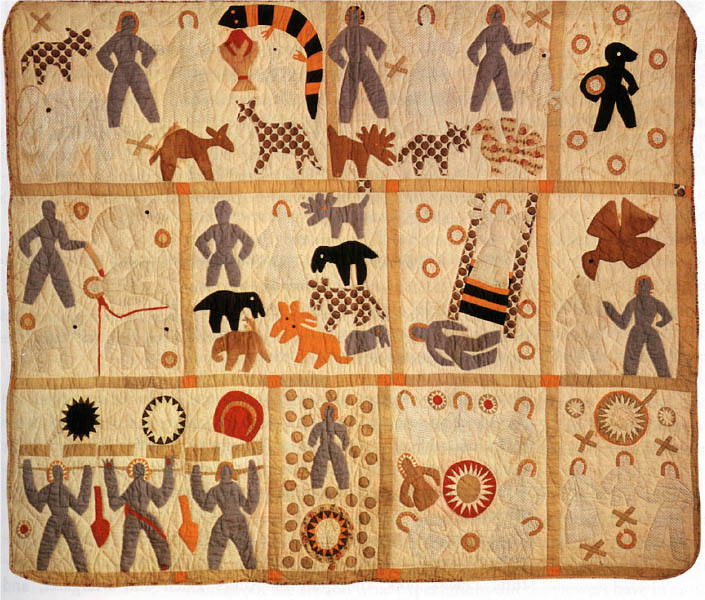

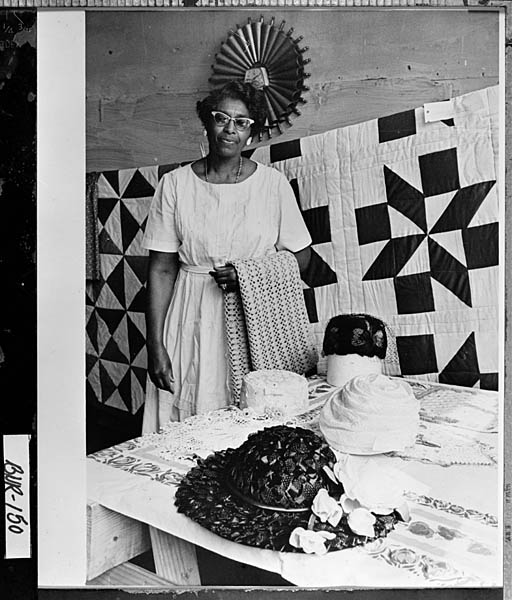

African Americans, both enslaved and free, made quilts. Slave owners typically either supplied families with purchased blankets or directed the production of thick whole-cloth comforters on the plantation. Some skillful seamstresses made fine quilts for their owners or clients, while others acquired fabrics to make quilts for their own use. Although most surviving nineteenth-century quilts made by African Americans resemble those made by European Americans, there is some evidence of the survival of African design elements. Harriet Powers of Athens, the most famous African American quilt maker of the nineteenth century, made quilts depicting historical events and Bible stories. Her pictorial motifs resemble West African ceremonial textiles.

The Civil War (1861-65) and Reconstruction affected all aspects of everyday life, including quilt making. The families of Confederate soldiers were required to supply their clothing and bedding. Many women returned to spinning and weaving when manufactured fabrics became unavailable. Shortages of sewing-machine needles, manufactured thread, cards, and other textile tools limited production. When Northern armies invaded, some families hid fine quilts and other valuables to save them from theft or destruction.

During the mid-nineteenth century, New England textile mills produced affordable fabrics, replacing imports for everyday clothing and household needs. As the southern economy improved after the war, quilt making became popular among middle-class women. Sewing machines enabled women to make family clothing more quickly, allowing more time for decorative sewing, including quilt making. Georgia quilts made in the second half of the nineteenth century display a wide variety of techniques, patterns, and color combinations.

Between 1880 and 1900 Georgia quilt makers took part in a popular international phenomenon of making what are known as crazy quilts. Women assembled irregularly shaped pieces of satin and velvet into random arrangements, then embellished them with embroidery. Too fragile for actual use as bedcovers, crazy quilts reflected the ornate decorative styles of the late Victorian era.

Popular periodicals, which circulated widely throughout the country in the 1890s, published quilt-pattern diagrams. As a result, regional patterns became distributed nationally, many new patterns emerged, and some old patterns were given names for the first time. The development of textile mills in southern states near the end of the century made fabric less expensive, and even poor families could afford fabric for quilts.

Twentieth Century

By 1900 upper- and middle-class women turned to other types of needlework, and quilts were considered old-fashioned and quaint. Georgia quilts from the first two decades of the twentieth century were typically made from fabrics left over from making everyday clothing.

Within a few years, however, the country experienced the Colonial Revival, a movement that encouraged Americans to emulate the activities and values of their pioneer ancestors. Urban middle-class women took up quilt making as a hobby, although the designs they produced were more influenced by such contemporary styles as art deco than by actual historical quilts. The popularity of quilt making during the 1920s and 1930s was fueled by women’s magazines and mail-order pattern companies. Many new patterns, such as Double Wedding Ring, Dresden Plate, and Little Dutch Girl, became very popular during this era. Fabrics used in quilts in this era included solid colors and prints, typically in pastel shades.

Quilt making declined during World War II (1941-45). During the 1950s quilt making continued as a low-profile activity, without attention from popular media. A renewed interest in quilt making emerged in the late 1960s and spread rapidly during the late twentieth century. Throughout Georgia, quilt clubs, called guilds, formed during the 1980s. Quilt guilds provide opportunities for their members to meet and to learn, and they sponsor public quilt shows and raise money for charitable causes.

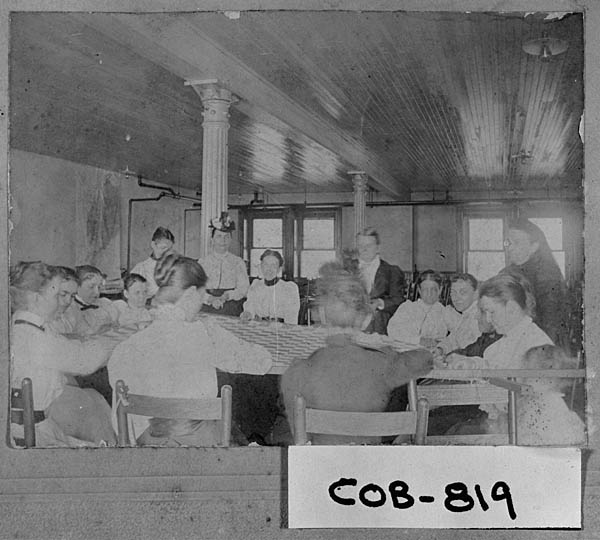

One widespread misconception is that the earliest American quilts were made by frontier settlers from scraps in the absence of other bedcovers, and that quilts only later developed decorative properties. During the late twentieth century, as scholars examined historic quilts and supporting documents, they published books and mounted exhibitions that more accurately portray the history of quilt making. Most notable is the 1998-99 exhibition Georgia Quilts: Piecing Together History, at the Atlanta History Center, based on the Georgia Quilt Project’s documentation of 8,100 quilts in the state.

Twenty-first Century

Georgia quilt makers continue to make quilts for the same reasons as earlier generations: to engage in a satisfying creative activity, to produce beautiful objects of lasting value for family and friends, and to make connections with other people.