The city of Hinesville is the seat of Liberty County. Located forty miles southwest of Savannah, the city is adjacent to Fort Stewart, making it home to many soldiers from the base.

Established in 1777, Liberty County changed its seat twice in fifty years, first moving it from Sunbury to Riceboro in 1797. After a majority of voters supported moving the county seat from Riceboro in 1836, Liberty County’s state senator Charlton Hines introduced legislation to establish a new seat within one mile of a place known as the General Parade Ground, which had been used by the county militia for drills and musters. This spot was more centrally located and was readily accessible to the Gulf and Western Railroad. In 1837 the new county seat was named Hinesville in honor of Hines.

Civil War

Before 1864 Liberty County was quite prosperous. Hinesville invested in naval stores, which are products from pine resin like turpentine, while plantations and farms produced indigo, rice, and cotton. All of this changed in the winter of 1864, when Union general William T. Sherman’s march to the sea reached the area.

Hinesville’s history during the Civil War (1861-65) includes a series of skirmishes in and around the town. With nearby Midway and Flemington under the control of the Seventh Illinois Infantry, Hinesville was a target for scouting and raiding parties. During a raid on December 1, W. P. L. Girardeau, ordinary of the county, was shot and severely wounded as he stood on the courthouse steps.

On December 16, the Seventh Illinois rolled through Hinesville. There they met a detachment of cavalry from Confederate general Alfred Iverson’s Army of Tennessee. After a skirmish through town, the Confederate detachment withdrew, and the march continued. Two days later, the Battle of the Altamaha Trestle, the bloodiest in coastal Georgia, took place, and the march was complete.

Liberty County was left devastated and in a state of chaos. Most plantations and farms in the county were destroyed, and citizens were hungry and destitute. Many people left in the wake of the march, afraid that displaced Confederate soldiers and freedpeople would loot and rob the area. The courthouse in Hinesville was deserted, and the naval stores industry ground to a halt.

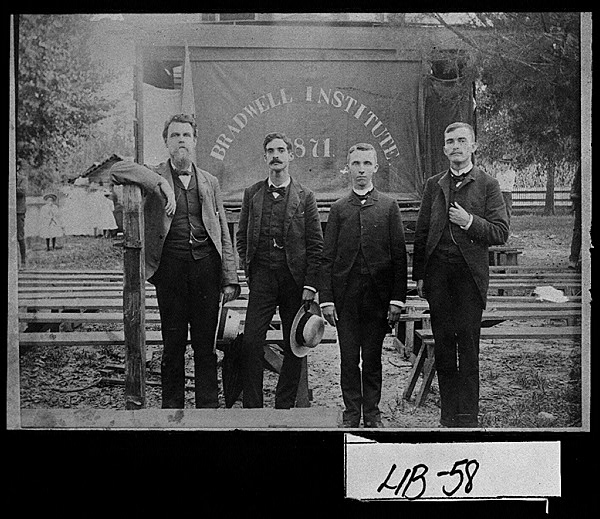

Bradwell Institute

No one is more responsible for uniting and rebuilding Liberty County than Samuel Dowse Bradwell. His father, James Sharpe Bradwell, was the original principal of Hinesville Academy, a private boarding school that closed during the Civil War, along with every other school in the county. As captain of the Liberty Volunteers, Samuel Bradwell was badly wounded in the Battle of Atlanta, but he managed to make it back to Hinesville.

After the war, the area had no schools for white children, but Dorchester Academy, an all-Black school, opened. In 1870 Bradwell reopened both the Poor School, a public school located on the outskirts of town, and Hinesville Academy, renamed Bradwell Institute after his father. The institute quickly became famous throughout Georgia for its high quality. The curriculum was the “highest grade in the country,” meant to “supersede the necessity of sending our boys and girls abroad to acquire finished educations.” The school grew from 63 to 465 students by 1938. Today Bradwell Institute is a public comprehensive high school.

Boomtown

Despite the success of Bradwell Institute, Hinesville remained a small, sleepy village. Its status as the county seat was all that kept it alive. The town steadily recovered from the devastation of the war and even utilized its natural mineral springs to become a health retreat at the turn of the century. Despite these small advances, hurricanes in 1928 and 1929 gave Liberty County a head start on the Great Depression, and its population in 1920 was just 315.

Hinesville’s economy improved in the 1930s, so there was much to celebrate at the town’s centennial in 1937. But nothing could prepare Hinesville, which had just hired its first policemen, for the events of 1940. That year a huge tract of land (280,000 acres) adjacent to Hinesville was selected to be an antiaircraft training site for the U.S. military. The new base was named Camp Stewart in honor of Liberty County’s Daniel Stewart, the great-great-grandfather of Eleanor Roosevelt, who was the wife of U.S president Franklin D. Roosevelt.

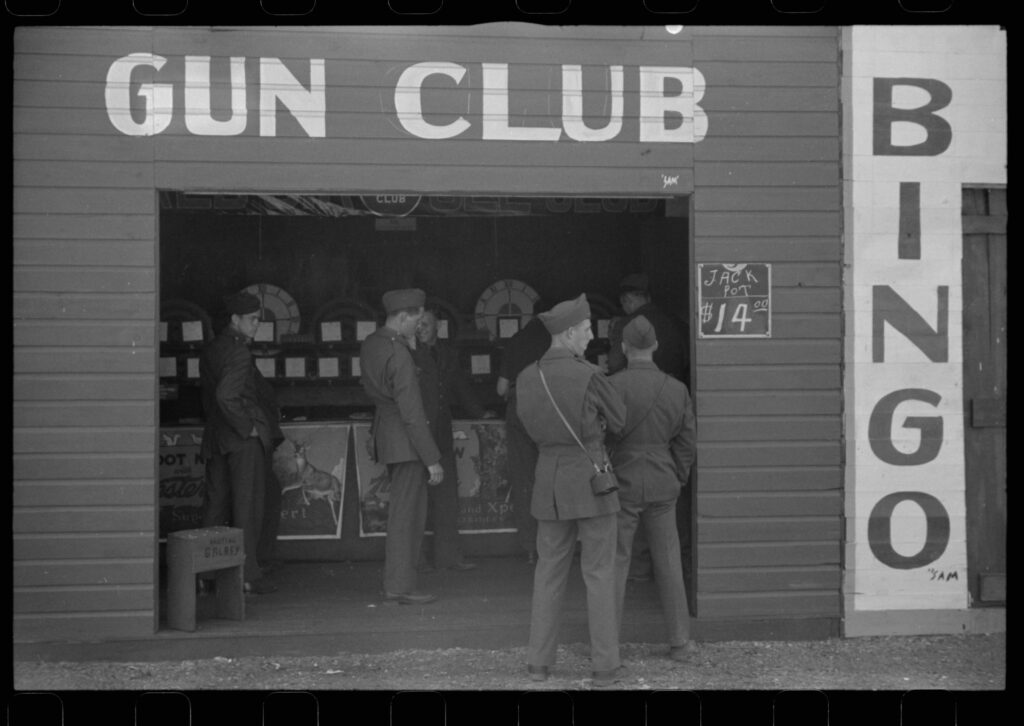

People began flocking to Hinesville to help build the base and to make their fortune from the influx of soldiers. Many businesses were temporary, makeshift constructions along two roads, called “Boomtown” and “Zoomtown,” that led from Camp Stewart to Hinesville. The roads were filled with juke joints, gambling houses, fast-food stores, bars, novelty stores, and two United Service Organizations (USO) clubs (one white, one Black).

By 1944 Camp Stewart teemed with 55,000 soldiers in the buildup of troops before the D-Day invasion. The city rushed to improve water, sewerage, garbage disposal, and streets. Still, dysentery, tuberculosis, and diphtheria were on the rise. Taxi and bus services were created. A movie theater was built, and the Methodist church was converted into a grocery store. Hinesville had no traffic lights, so military police had to direct traffic. Prostitutes roamed the streets alongside hogs, cattle, and mules. Syphilis and gonorrhea were rampant. The city even turned to child labor when many city workers went to Camp Stewart to earn higher wages. These children earned as much as schoolteachers, but instead of cleaning up the city, they roamed the streets, stealing and abusing property.

Lasting Impact of Fort Stewart

After World War II ended in 1945, Camp Stewart was deactivated, and Hinesville deflated. However, subsequent international conflicts made the base indispensable. In 1956 the base was designated a fort, and in 1974 Fort Stewart’s permanence was solidified by the arrival of the Twenty-fourth Infantry Division (inactivated in 1996) and the Seventy-fifth Infantry Regiment (Ranger). Since the 1970s, Hinesville has grown from a town of around 4,000 to a city of 34,891, according to the 2020 U.S. census. The city’s growth is fueled by that of Fort Stewart, and the fates of the two communities are inextricably tied, as the soldiers rely on the city’s service and retail industry.