John Hope was an important African American educator and race leader of the early twentieth century. In 1906 he became the first Black president of Morehouse College—the alma mater of Martin Luther King Jr.—in Atlanta. Twenty-three years later, in 1929, Hope went on to become the first African American president of Atlanta University (later Clark Atlanta University).

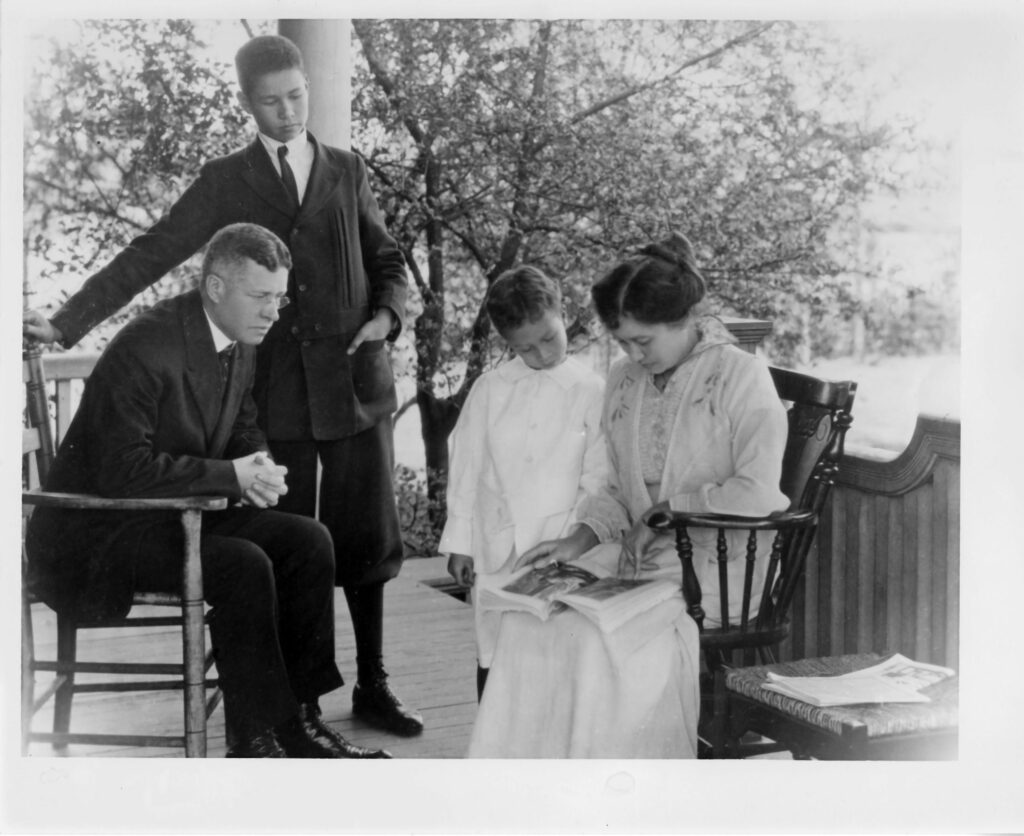

Courtesy of Atlanta University Center, Robert W. Woodruff Library Archives.

To accomplish his goals, Hope embraced several civil rights organizations, including W. E. B. Du Bois’s Niagara Movement, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), and the southern-based Commission on Interracial Cooperation. He was also very active in such social service organizations as the National Urban League, the “Colored Men’s Department” of the YMCA, and the National Association of Teachers in Colored Schools. Hope was very well known among both Blacks and whites in the early twentieth century. Buck Franklin, the father of the distinguished historian John Hope Franklin, was so impressed with Hope’s social and educational leadership that he named his son after Hope.

Early Life and Education

John Hope’s early life contributes much to an understanding not only of racial identity but also of class, color, and caste among African Americans, especially in the South. Born of a biracial union in Augusta on June 2, 1868, he belonged to a small Black elite whose history predated the end of slavery. His father, Scottish-born James Hope, immigrated to New York City early in the nineteenth century and eventually moved to Augusta, where he became a prominent businessman. His mother, Mary Frances Butts, was a free African American woman born in Hancock County. Although Georgia law prohibited interracial marriages, Hope’s parents lived openly as husband and wife until his father’s death in 1876.

The elder Hope’s death marked a watershed in his eight-year-old son’s life. The executors of the elder Hope’s estate failed to carry out his plans to provide a secure financial future for his family. After his father’s death, Hope’s position as a member of the Black elite stemmed not from belonging to a household with a wealthy white head but from his heritage of pre–Civil War (1861-65) free Black ancestry.

Hope’s education prepared him for his life’s work. Though he quit school after the eighth grade to help his struggling family survive, he decided five years later to complete his education and attended a preparatory school in Worcester, Massachusetts, in 1886. He went on to earn a B.A. degree in 1894 at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island. Hope eventually decided to become a professional educator, teaching first at Roger Williams University, a small Black liberal-arts school on the outskirts of Nashville, Tennessee. In 1897 Hope married Lugenia Burns, who would also become a prominent race leader and social activist.

Atlanta Years

Hope and his wife moved in 1898 to Atlanta, where he took a teaching position at Atlanta Baptist College, which became Morehouse College in 1913. It was in Atlanta that Hope first met and befriended prominent Black leaders and educators like Booker T. Washington and W. E. B. Du Bois. In 1906 he assumed the presidency of the college and remained in that position until 1929, when he moved to the presidency of Atlanta University.

Under his leadership, Atlanta University became the first college in the nation to focus exclusively on graduate education for African American students. As a race leader, Hope was steadfast in his support of public education, adequate housing, health care, job opportunities, and recreational facilities for Blacks in Atlanta and across the nation. He also supported full civil rights in the South during an era when African Americans were expected to accommodate a system of inequality.

Hope faced many dilemmas throughout his adult life. Most vexing was his attempt to balance the demands of his job as president of a Black college with his role as a national leader committed to a program of full civil rights. Hope was somewhat reluctant to give up good faculty and administrators who went on to serve in such organizations as the NAACP. He frequently contemplated leaving Morehouse and becoming a professional race leader himself, pondering, though ultimately rejecting, offers from the NAACP, the Urban League, and the National Council of the YMCA. His deep involvement in race matters often strained his relationship with the prominent white liberals and philanthropists who were influential in the continuing development of Black higher education, especially after the death of Booker T. Washington. Yet in spite of these difficulties, Hope was as influential in the development of African American college education as Washington had been in the development of African American vocational education.

Hope died of pneumonia in 1936 at the age of sixty-seven. His papers are held at the Robert W. Woodruff Library at the Atlanta University Center.