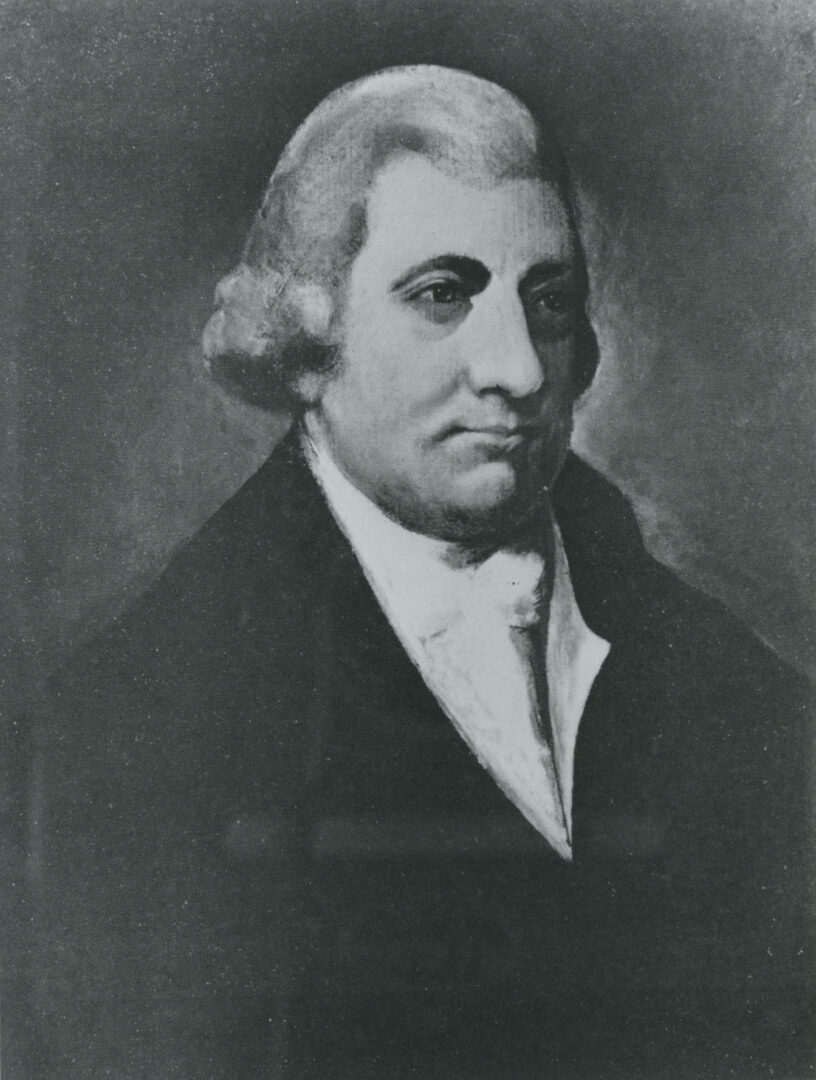

John Houstoun was twice governor of Georgia, the first mayor of the city of Savannah, and an early supporter of independence from Britain. He commanded the Georgia militia in the invasion of Florida during the American Revolution (1775-83) and represented Georgia in the Continental Congress. Houston County, in central Georgia, is named in his honor.

The date and place of Houstoun’s birth are not known. The best evidence indicates that he was born sometime between 1746 and 1748 in either Frederica or on the Houstoun plantation, Rosdue. Houstoun’s father was Sir Patrick Houstoun, fifth baronet of Scotland, who was one of the earliest settlers of the colony of Georgia. His mother, Priscilla Dunbar, came from Scotland to Georgia in 1736. John Houstoun married Hannah Bryan, though the date of this union is unknown. They had no children.

Revolutionary Statesman and Defender of Liberty

Houstoun practiced law in Savannah for many years before he began his career in politics. In 1774 he joined Archibald Bulloch, George Walton, and Noble W. Jones in calling for a meeting of “all persons” to discuss “the arbitrary and alarming” acts of the British government. In 1775 Houstoun attended the Georgia Provincial Congress as a representative from Savannah. There he was elected as one of five delegates to represent Georgia at the Continental Congress. Of these five, three—Houstoun, Bulloch, and the Reverend John J. Zubly —traveled to Philadelphia and became Georgia’s first representatives at the Continental Congress.

Courtesy of Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries.

Houstoun, Bulloch, and Zubly were suitable choices for this responsibility. Each represented a major faction of those in Georgia who opposed the policies of the British. Bulloch represented the large numbers of Georgians who favored independence from Britain and supported the measures to stop the importation of British goods. Zubly represented the many who opposed both independence and the nonimportation agreements. Houstoun spoke effectively for those who favored independence but opposed the restrictions on trade called for by the policies of nonimportation. Early in his tenure at Congress, Houstoun joined Zubly in favoring measures designed to relax some of the requirements of the nonimportation agreements. In 1776, though elected to serve, he did not return to Congress and thus did not sign the Declaration of Independence. Instead, he remained in Georgia, where he provided effective opposition to Zubly’s efforts to convince the citizens of Georgia to oppose independence.

Revolutionary Governor and Soldier

On January 8, 1778, Houstoun was elected Georgia’s second governor. Conservatives such as Lachlan McIntosh, who felt aggrieved by the policies and actions of Georgia’s first governor, the radical John Treutlen, welcomed Houstoun’s election. His first order of business was to improve the miserable military position of the new state.

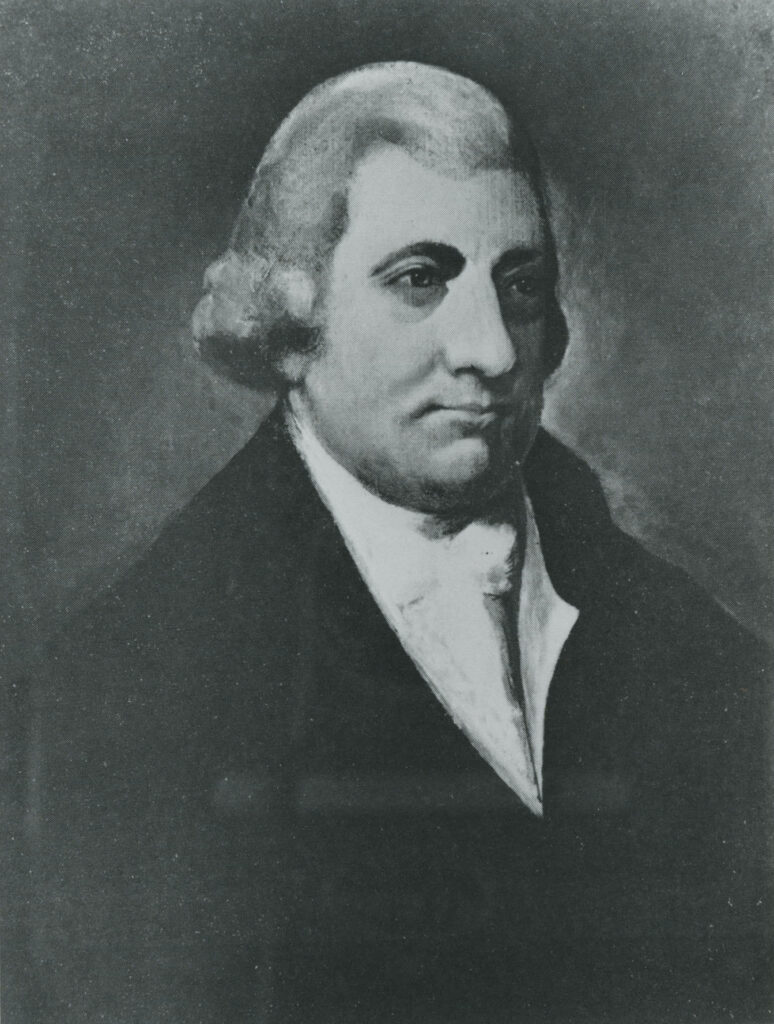

Courtesy of Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries.

In 1778 hundreds of Loyalists from Georgia and the Carolinas were making their way to the British fort at St. Augustine, Florida. On their way through Georgia, they robbed and plundered farms and towns. Houstoun believed that the British were amassing an army in St. Augustine, which was known to many Americans as “that Pestiferous nest.” He took the lead in organizing an invasion force consisting of troops under the commands of the Continental Congress and of the states of Georgia and South Carolina. In the spring and summer of 1778, Governor Houstoun personally commanded the troops of the Georgia militia in this campaign, hoping to drive the British out of Georgia and to invade Florida and take St. Augustine.

After the American troops succeeded in forcing the British out of Georgia, the commander of the Southern Department of the Continental army, Major General Robert Howe, determined that the British forces in Florida would not cross the St. Marys River to invade Georgia, and thus he opposed Houstoun’s plan to capture St. Augustine. Without the support of the Continental army, Houstoun’s plan to invade Florida failed. The Americans, suffering from disease, desertions, and dissension, returned to Savannah. The Continental Congress shared some of the blame for this failure. South Carolinian Henry Laurens, former president of the Continental Congress, observed that Congress was prevented from aiding Houstoun and the patriotic Georgians by the “venality, peculation, and fraud” that permeated that august body.

The failure of the military campaign to remove the British threat from Florida left Georgia open to invasion and conquest. On December 29, 1778, Savannah and Georgia fell to the British, and “one star and one bar” were removed from the American flag. Governor Houstoun’s last official act was to flee the capital city of Savannah in time to avoid capture by the British troops.

Defender of Georgia’s Interests

The British left Savannah in 1782. Houstoun was elected governor of Georgia for a second one-year term in 1784. In 1787 he served on a commission to settle boundary disputes with South Carolina. Houstoun refused to sign the agreement reached by this commission, believing that it gave to South Carolina land that rightfully belonged to Georgia. Today’s map reflects the legacy of this agreement: the boundary between the two states suggests that South Carolina did indeed take a small bite out of Georgia’s northeast corner.

In 1790 Houstoun was elected as the first mayor of Savannah. He was reelected in 1791 but declined to serve. The same year, he was elected judge of the Superior Court of Georgia. In 1792 he was appointed president of Chatham Academy. On July 20, 1796, Houstoun, a lifelong defender of the liberties and interests of the citizens of Georgia, died at his home in White Bluff, near Savannah.