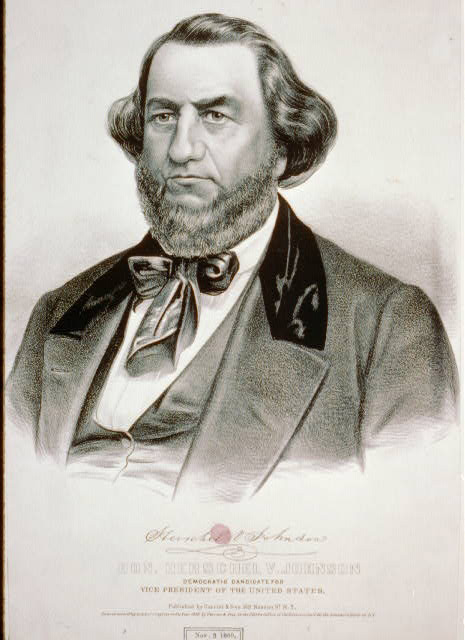

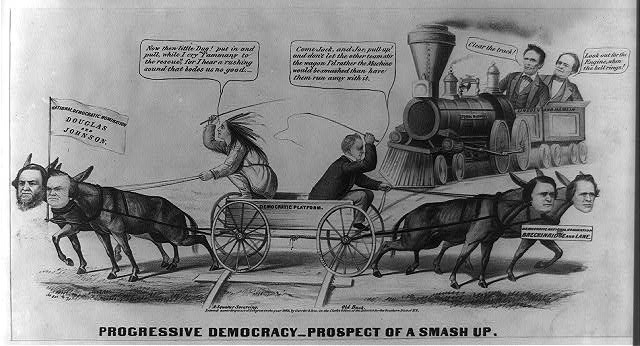

Perhaps most famous as Stephen Douglas’s 1860 vice presidential candidate, Herschel Johnson played an anomalous but central role in the heated sectional politics of the 1850s and 1860s. Taken as a whole, his contradictions encapsulate the intense uncertainty Georgians felt toward disunion, especially in the years before the Civil War (1861-65). Johnson County, in east central Georgia, is named in his honor.

Early Life and Career

Herschel Vespasian Johnson was born on September 18, 1812, in Burke County. Like most of Georgia’s antebellum political lights, Johnson passed through the University of Georgia, graduating in 1834. He took up the law and established prosperous practices in Augusta, Louisville, and finally Milledgeville, the state capital. Ambrose Wright, the future Confederate officer and newspaper journalist, began his study of law in Johnson’s Louisville office. In 1844, the same year he moved to Milledgeville, Johnson served as a Democratic presidential elector, and in 1847 he tried in vain to secure the party’s gubernatorial nomination. In 1848 Johnson was appointed to fill the U.S. Senate seat vacated by Walter Colquitt, which he occupied for a little more than a year before returning home to serve as a superior court judge.

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

After the Nashville Convention of 1850, Georgia governor George W. Towns called for a state convention that would meet in December to consider secession. Johnson, with Towns, led the Southern Rights Democrats, who were opposed by a powerful Constitutional Unionist coalition headed by Howell Cobb, Alexander Stephens, and Robert Toombs. However, sectionalist sentiment was not yet strong enough in historically moderate Georgia, and the Constitutional Unionists buried the states’ rights men at the polls, guaranteeing that Georgia would not secede at that time and dampening enthusiasm for the separatist movement throughout the South.

From Secessionist to Moderate

Nevertheless, the 1850s turned out to be an extraordinarily active political decade for Johnson, one in which the man who had once plumped vigorously for Georgia’s states’ rights would undergo an astonishing conversion. In 1852 he served once again as a presidential elector, and in 1853 he was elected governor. He was reelected in 1855. By mid-decade, the possibility of southern secession was again being openly rumored. But this time Governor Johnson—disabused of his former belief in the vitality of separatism by the events of 1850—dismissed the idea that any sizeable number of southerners harbored ambitions to sever their region’s ties to the Union.

This stance won Johnson a reputation for moderation, which led in turn to his nomination for vice president by the Douglas Democrats in 1860. When the secession issue emerged after the election, Johnson spoke out forcefully against disunion. Although he certainly embodied the southern ambivalence toward the North, his path from secessionist in 1850 to unionist in 1860 inverted the trajectory of the South as a whole over the same period. Johnson changed his mind not out of any great fondness for the North but because he had become convinced that slavery was much more secure within the Union than outside of it.

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Johnson served the rest of his career with quiet distinction. Once the decision for disunion was made, he reluctantly went along with his state, even serving as a Confederate senator from 1862 to 1865. After the war, he was elected, along with Alexander Stephens, to the U.S. Senate under Andrew Johnson’s Reconstruction scheme, but like all of those elected to Congress from Georgia in early 1866, he was not seated. He then returned to Louisville and resumed his career as an attorney. After 1873 he served as a judge until his death on August 16, 1880.