As a member of the last generation of African Americans born and educated on Sapelo Island, Cornelia Bailey became one of Georgia’s most vocal defenders of her homeland and its African American heritage.

Sapelo Island, a barrier island off the southern coast of Georgia, has protected the state’s interior for thousands of years. Although the island has withstood countless hurricanes and the arrival of colonial settlers, a new threat has come to the people of Sapelo—the threat of industrial development.

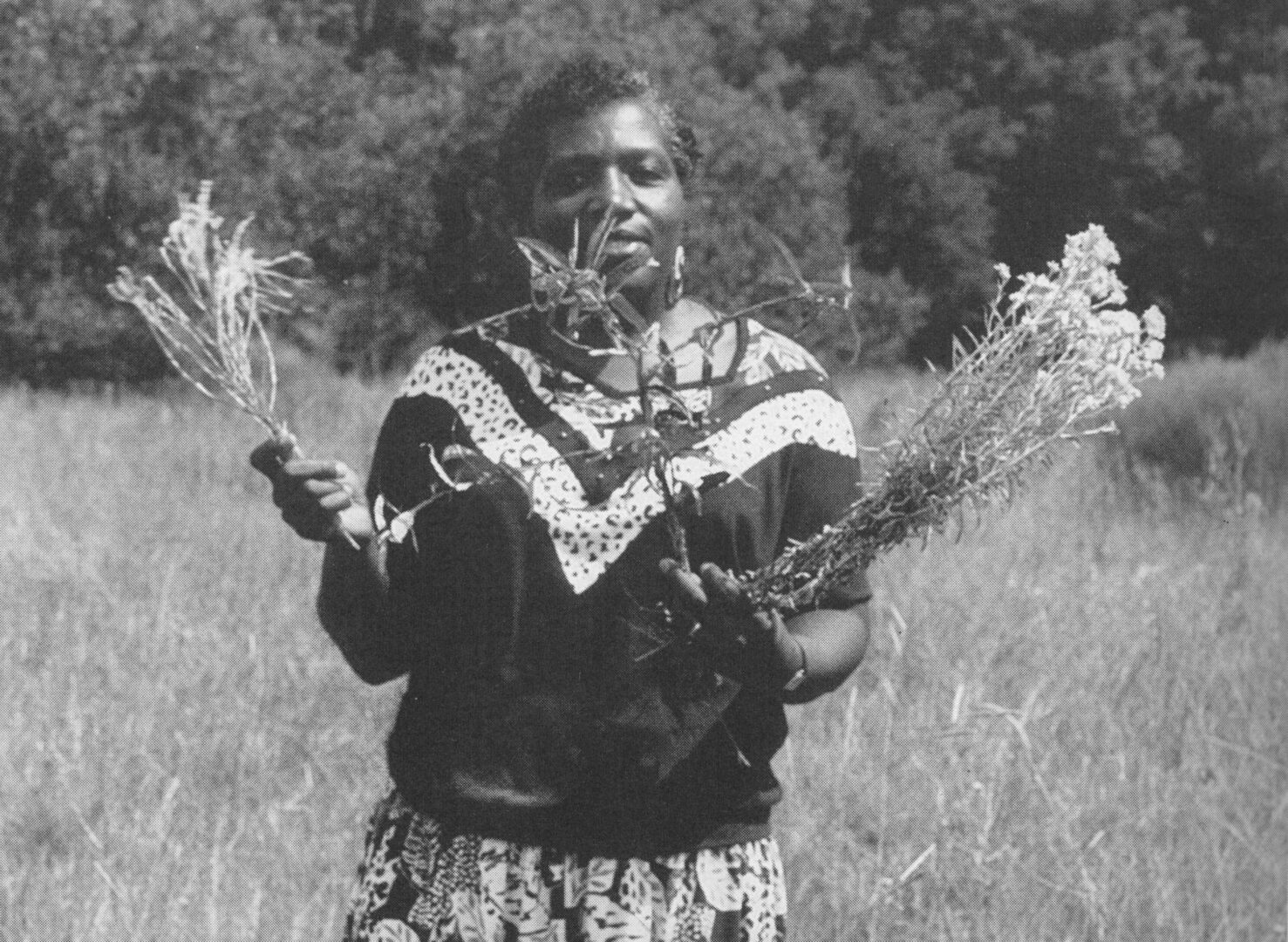

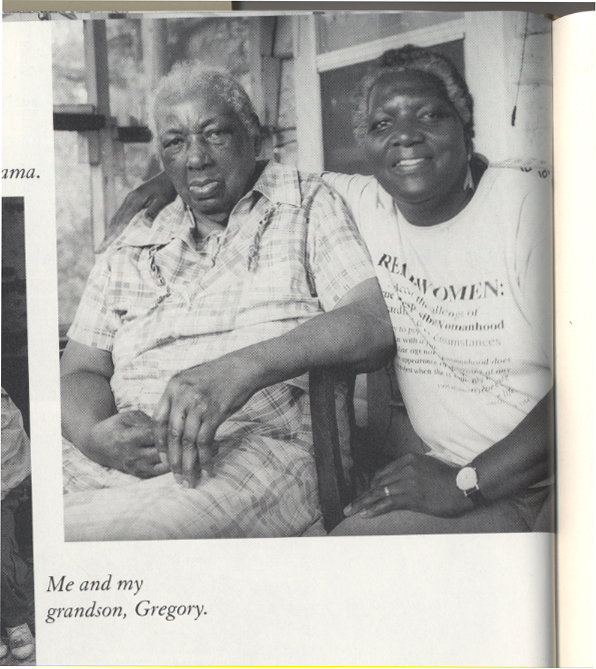

A self-proclaimed “Saltwater Geechee,” Cornelia Walker Bailey was born on Sapelo on June 12, 1945, to Hettie Bryant and Hicks Walker. In 2000 she published God, Dr. Buzzard, and the Bolito Man, a cultural memoir that both details Bailey’s experiences while growing up on Sapelo Island in the 1940s and 1950s and gives its readers a new perspective on the African American culture that emerged on the island more than 200 years ago. Using childhood stories and family legends passed down over generations, Bailey depicts a way of life that has become threatened by the industrial development that creeps closer and closer to Sapelo.

Bailey traced her lineage back to an African Muslim named Bul-Allah (or Bilali), who worked as the head manager of enslaved people for the island’s owner and enslaver, cotton planter Thomas Spalding. Cornelia Bailey and her family, like many of Sapelo’s natives, are direct descendants of West African enslaved people, many of whom (like Bilali) were Muslim. Over time, the different cultures living on Sapelo Island have blended together and become what Bailey calls the Geechee culture. A combination of Christian and Islamic religious beliefs, the Geechee culture on Sapelo Island has remained virtually unchanged, thanks to the island’s geographic isolation.

After living with family members on St. Simons Island for some years, Bailey returned to Sapelo in 1966 to become the island’s “griot,” an African term for the tribal historian who, in Bailey’s own words, keeps “the oral history of the tribe, as it [has been] passed down for thousands of years.” She and her husband, Julius “Frank” Bailey, conducted tours of the island and taught others about their community’s rich and treasured history.

Bailey fought against the loss of her community’s cultural heritage her whole life. However, as Sapelo’s elders pass on and the island’s youth are forced to leave Sapelo for education or work, the Geechee community struggles to maintain its historical identity. The state of Georgia currently owns about 95 percent of Sapelo Island, leaving residents confined to a small, private portion of the island known as Hog Hammock. Bailey worked to raise awareness of Sapelo’s plight by educating those who visit Sapelo Island through public speaking and writing. In May 2004 she received a Governor’s Award in the Humanities in recognition of her work on behalf of the African American population of Sapelo Island and the Geechee culture.

Bailey died on October 15, 2017.