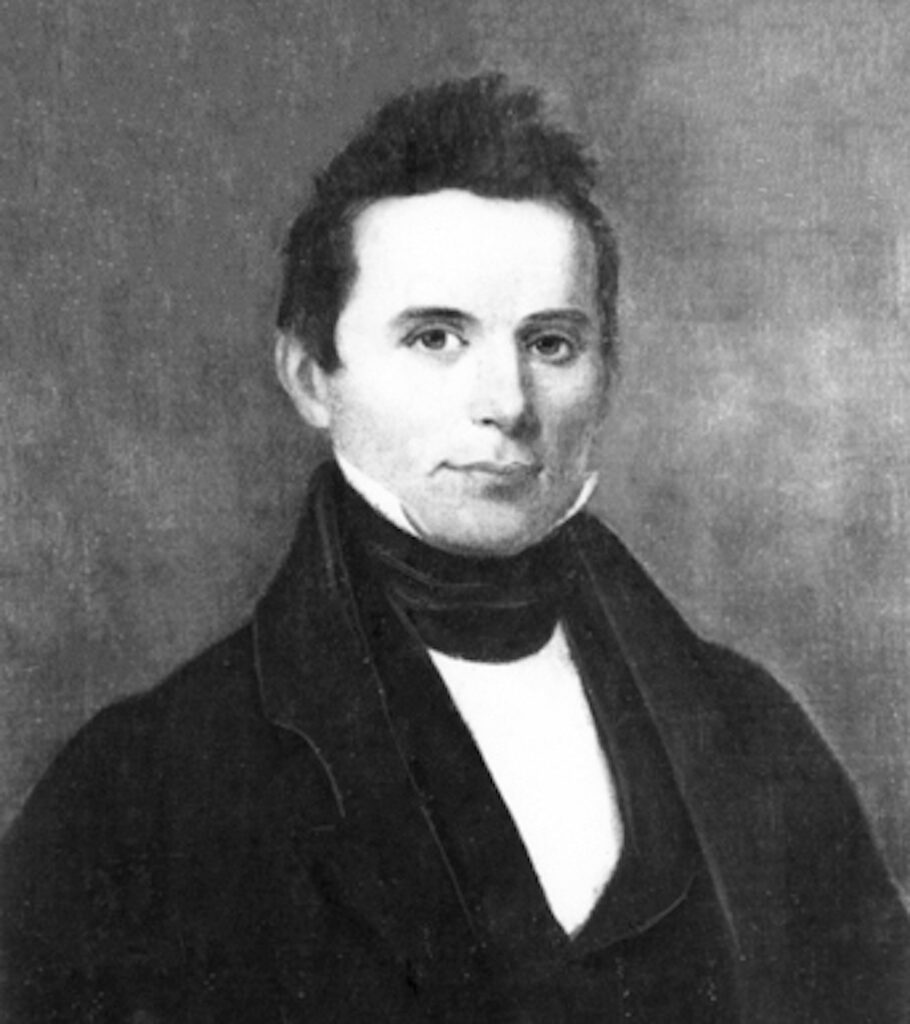

Elias Boudinot was a formally educated Cherokee who became the editor of the Cherokee Phoenix, the first Native American newspaper in the United States. In the mid-1820s the Cherokee Nation was under enormous pressure from surrounding states, especially Georgia, to move to a territory west of the Mississippi River. Ultimately, the Cherokee Nation was divided, with the majority opposing removal, and a small but influential minority, including Boudinot, favoring removal. As an educator, an advocate of Cherokee acculturation, and editor of the Phoenix, Boudinot played a crucial role in Cherokee history during the decades preceding the Nation’s forced removal, often referred to as the Trail of Tears.

Image from Oklahoma Historical Society

Elias Boudinot was born in Oothcaloga, in northwest Georgia, about 1804. He was called Gallegina, or the Buck, and was the eldest of nine children. His father, Oo-watie, was considered a progressive Cherokee. Oo-watie enrolled Gallegina and a younger son, Stand Watie, later a Confederate general, in a Moravian missionary school at Spring Place, in northwest Georgia. In 1817 young Gallegina was invited to attend the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions school in Cornwall, Connecticut. On his journey there, Gallegina was introduced to Elias Boudinot, the aged president of the American Bible Society, and adopted his name in deference and tribute.

Boudinot spent several successful years at the American Board school, and in 1820 he converted to Christianity. Four years later he became engaged to a white woman, Harriet Ruggles Gold, the daughter of a Cornwall physician. Their engagement ignited a firestorm of racial prejudice, and the betrothed couple was burned in effigy. Labeled a breeding ground for mixed couples, the American Board school was forced to close immediately. Boudinot and Harriet Gold married in 1826, then returned to High Tower in the Cherokee Nation to work in a mission.

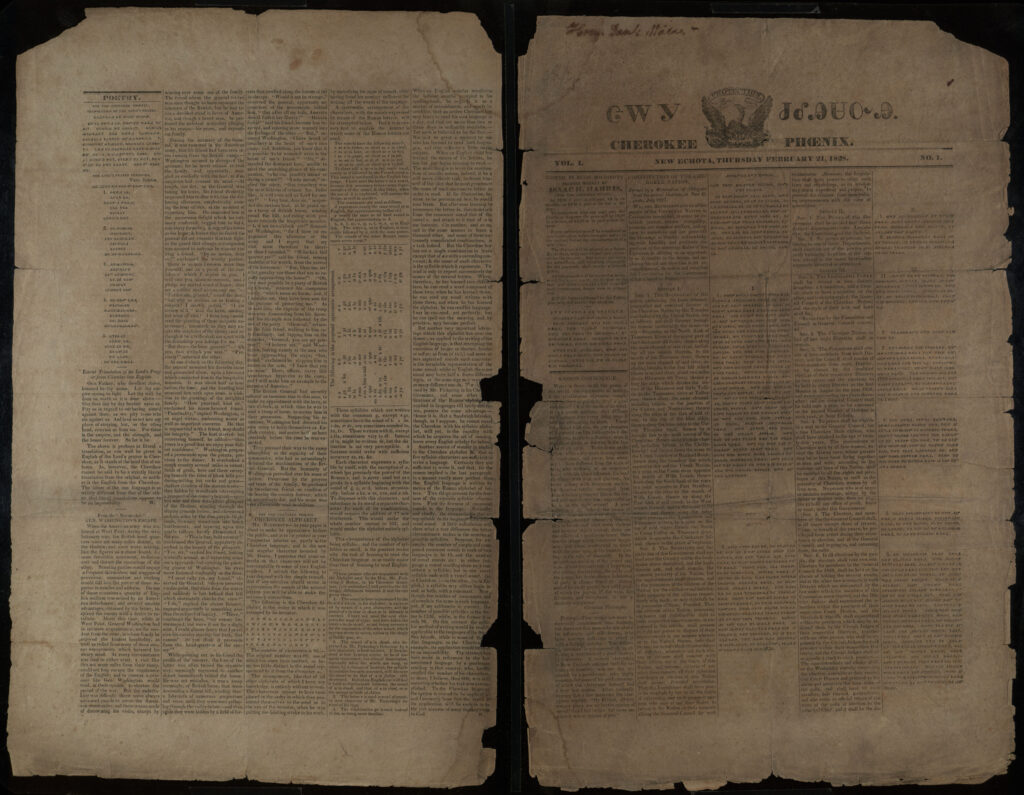

Earlier in the spring of 1826 Boudinot had embarked on a national speaking tour to elicit financial, spiritual, and political support for the Cherokee Nation’s continuing progress in the “arts of civilization.” His pamphlet, “An Address to the Whites” (1826), was based on a speech he made in Philadelphia. Boudinot proved remarkably effective at fund-raising. By 1827 the General Council of the Cherokee Nation was able to purchase a printing press and Cherokee typeface for the publication of a national newspaper, with Elias Boudinot as its editor. The groundbreaking first issue of the bilingual periodical, known as the Cherokee Phoenix, appeared on February 21, 1828. Boudinot pledged to print the official documents of the Nation and tracts on religion and temperance, as well as local and international news.

Courtesy of Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries.

In the years following the Indian Removal Act (1830) Boudinot also began to publish editorials in favor of the voluntary removal of the Cherokees to a territory west of the Mississippi River. But his opinions were at odds with those held by the majority of the Nation, including the General Council. He resigned as editor of the Phoenix in August 1832 but continued to take an active role in the removal crisis and even printed a pamphlet attacking anti-removal chief John Ross. He ultimately signed the New Echota Treaty (1835), which required the Cherokees to relinquish all remaining land east of the Mississippi River and led to their forced removal to a territory in present-day Oklahoma. Soon after moving west with his family in 1839, Boudinot and two other treaty signers (his uncle Major Ridge and cousin John Ridge) were attacked and stabbed to death by a group of Ross supporters.

Boudinot was inducted into the Georgia Writers Hall of Fame in 2005.