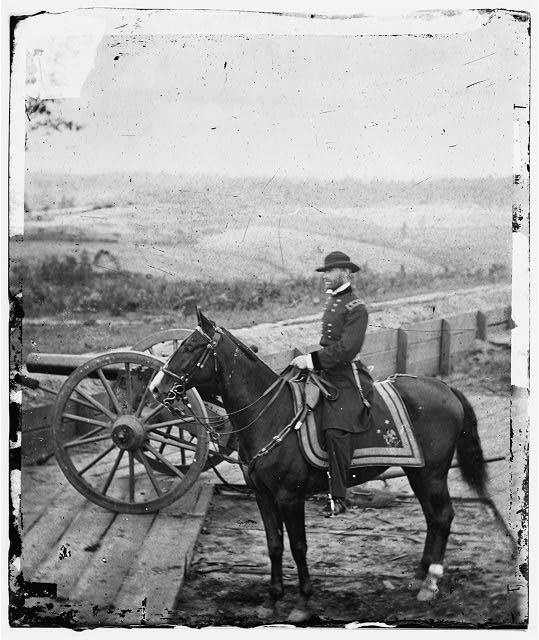

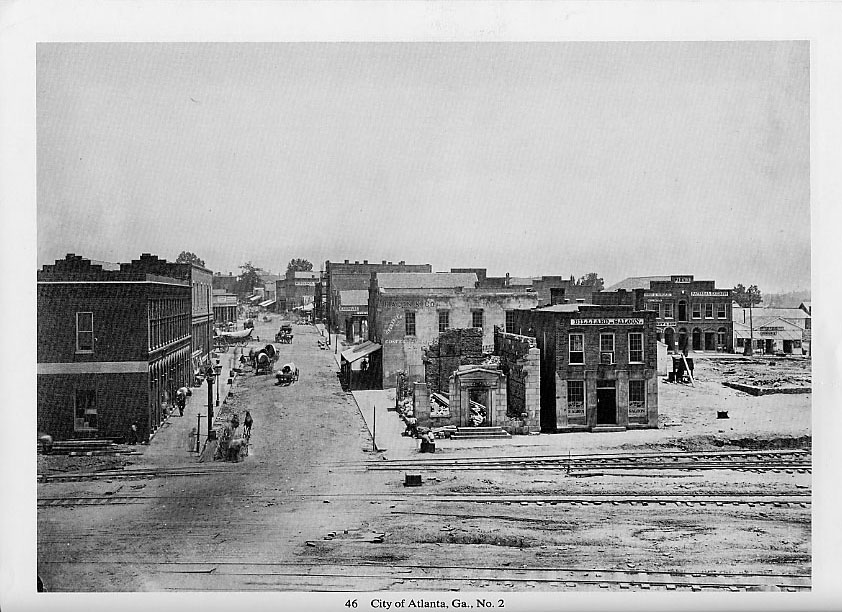

A pioneer of nineteenth-century photography, George N. Barnard is best known for his work during the Civil War (1861-65) as the official army photographer for the Military Division of the Mississippi, commanded by Union general William T. Sherman. His images, first published in 1866 as a limited collector’s edition entitled Photographic Views of Sherman’s Campaign, record the destroyed landscapes and gutted cities left in the wake of Sherman’s Atlanta campaign and subsequent march to the sea.

From Photographic Views of Sherman's Campaign, by George N. Barnard

Born in Connecticut on December 23, 1819, George Norman Barnard was producing daguerreotypes (the first photographs commercially available to the public) by the age of twenty-three, and in 1846 he opened his first studio in Oswego, New York. In 1853 fire destroyed the massive grain elevators in Oswego, and Barnard, capturing the event with his camera, created some of the first “news” photographs known to historians.

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Barnard opened a studio in Syracuse, New York, in 1854, but a poor economy forced its closure. Finding employment with Edward Anthony’s studio in 1859, Barnard worked in New York City on stereoscopes (a double photograph that, when seen through a special viewer, becomes fused into a single image with a three-dimensional quality). Mathew Brady, a famous daguerreotypist with studios in New York and Washington, D.C., hired Barnard as a portrait photographer and sent him to Washington to photograph Abraham Lincoln’s 1861 inauguration as president of the United States.

By the late 1850s the daguerreotype had given way to the new collodion process, which required the near proximity of a darkroom, where negatives could be developed on the spot. (Called the “wet plate” process, glass plates coated with a collodion and halide salt mixture were dipped in a silver-nitrate solution and exposed while moist, developing the negative at once. Once the collodion dried, the photograph could not be processed.)

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

When the Civil War broke out, Brady formed a crew of cameramen, “Brady’s Photographic Corps,” to document the conflict and the men who fought in it. In 1862, using a tent or wagon as his darkroom, Barnard produced the earliest known collodion photographs at the site of the Bull Run battle in Virginia.

In December 1863 the veteran photographer returned to the battlefield, this time as the official photographer for the Military Division of the Mississippi, with headquarters in Nashville, Tennessee. Barnard’s main function, as an employee of the Topographic Branch of the Department of Engineers, was to duplicate maps and documents and to photograph fortifications and bridges. During the early months of 1864, Barnard photographed the landscape of East Tennessee and then worked in Nashville to create detailed topographic maps, which Sherman utilized as his troops moved from Chattanooga, Tennessee, to Atlanta.

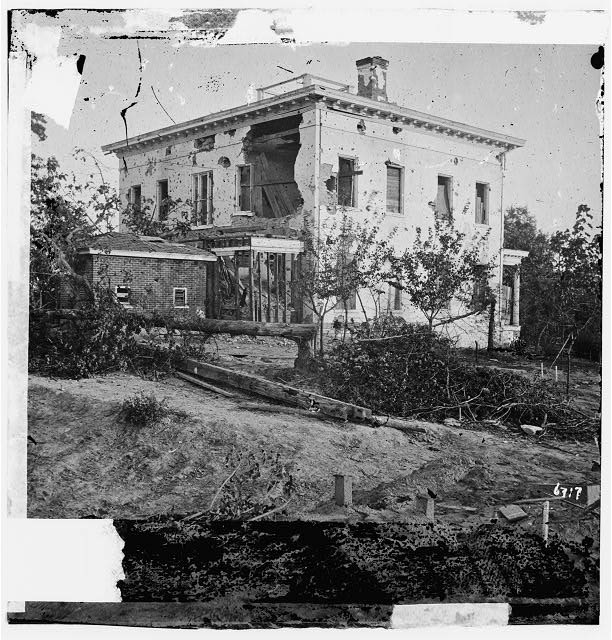

From Photographic Views of Sherman's Campaign, by G. N. Barnard

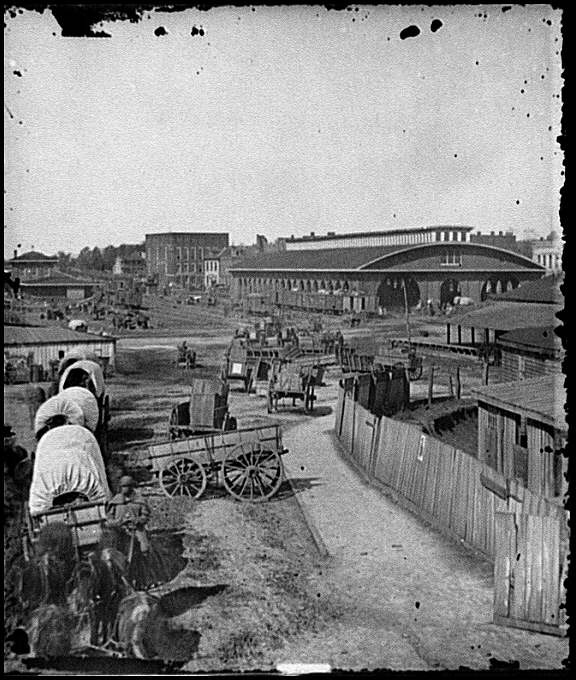

Barnard traveled to the Atlanta front on September 11, 1864, after Sherman had captured the city. Over the next two months, he photographed Confederate fortifications, railroad yards, private homes, and city streets. Sherman’s troops departed Atlanta in November and marched toward the coast. Barnard took no photographs during the march until he reached Fort McAllister, near Savannah, which Union forces captured in December. He remained in Savannah, duplicating maps of the march route, until late January.

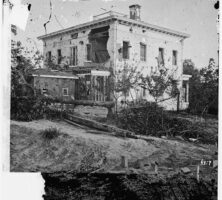

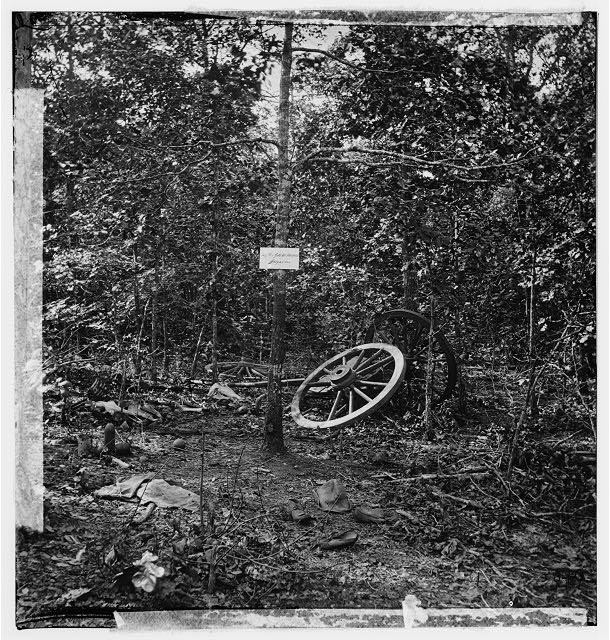

Barnard’s equipment was cumbersome, and with Sherman’s army almost constantly on the move, the photographer could not take all the images he wanted to during the campaign. Following Confederate general Joseph E. Johnston’s surrender to Sherman in 1865, Barnard revisited many of the key battle sites in Georgia to produce the body of work for which he is now best known. The majority of the finished sixty-one prints illustrate a landscape of trees shorn by gunfire and cities of empty streets and ruined buildings, an eerie and mute testament to the brutal power of war.

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

One of these photographs depicts the death site of Union general James B. McPherson. While surveying the Union lines along the outskirts of Atlanta on July 22, 1864, McPherson, surprised by several Confederate troops, ignored their call to surrender. Attempting to escape on horseback into the trees, he was struck in the back by a rifle bullet, dying within minutes.

Barnard had taken several photographs of the scene soon after his arrival in Atlanta in 1864. Returning after the war, he found the death site largely preserved; however, this time he was able to experiment, shooting the scene from different angles and adjusting several elements, such as the amount of visible foliage and debris in the frame. The resulting photograph highlights the bleached-out bones of a horse skeleton, suggesting the general’s failed attempt to escape on horseback. Balancing an awareness of history with an understanding of aesthetics, Barnard’s landscape is a haunting testament to the war’s destruction.

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

By 1869 Barnard had established a new studio in Chicago, Illinois, but it was destroyed in the great fire of 1871. Using borrowed equipment, he then recorded the process of rebuilding the city in a series of photographs that recall his Civil War scenes. He went on to promote the new gelatin dry process in collaboration with George Eastman in New York and later opened a studio in Painesville, Ohio, in 1884. Barnard died at his daughter’s home in New York, on February 4, 1902, not far from his first studio.