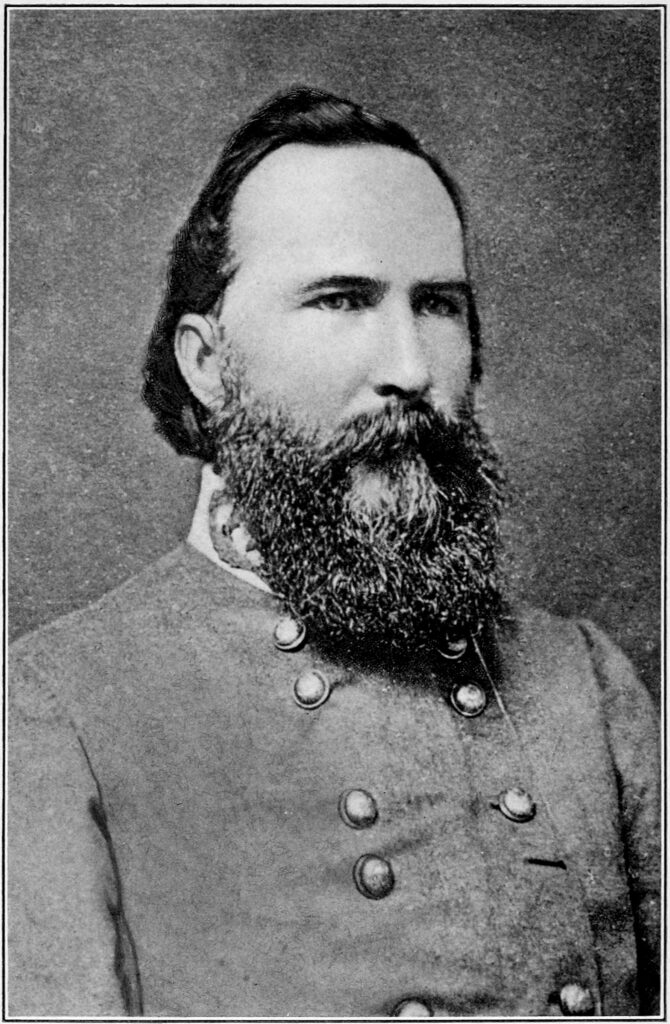

A veteran of the Mexican War (1846-48) and a Republican politician, James Longstreet was one of the most prominent and controversial figures of the Civil War (1861-65).

Early Life

Born on January 8, 1821, in the Edgefield district of South Carolina, not far from Augusta, Longstreet always considered himself a Georgian. His parents, Mary Anna Dent and James L. Longstreet, owned a cotton plantation in northeast Georgia, where as a boy he thrived in the rough frontierlike conditions. At the age of nine, Longstreet moved to Richmond County to live with his uncle Augustus Baldwin Longstreet and to attend the prestigious Richmond County Academy. The death of Longstreet’s father in 1833 and his mother’s subsequent move to north Alabama intensified Augustus Longstreet’s influence over the young man.

When the time came to choose a career, Longstreet gained an appointment to the U.S. Military Academy in West Point, New York, with the help of his uncle and other influential politicians, including John C. Calhoun. Strong, independent, and gruff in speech and manners, Longstreet dreamed of a soldier’s life. After graduation from the academy in 1842, he served in the Mexican War and on the frontier. But secession and the Confederacy ultimately defined Longstreet’s military career, as he rose to the rank of general and second-in-command of Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. He later became the scapegoat for that army’s most costly defeat.

Confederate “War Horse”

The Civil War defined Longstreet’s life. Although he played but a minor role in the First Battle of Manassas, fought in Virginia in July 1861, he won the admiration of his superiors. Under Joseph E. Johnston, Longstreet turned in one of his worst performances at the Battle of Seven Pines in Virginia on May 31, 1862. Johnston’s wounding during that battle required Longstreet to prove himself anew to Johnston’s successor, Robert E. Lee. His solid performance during the Seven Days battles on Virginia’s peninsula earned him Lee’s trust, as evidenced by his appointment as Lee’s senior lieutenant in command of the Army of Northern Virginia’s I Corps. A few months after assuming army command, Lee referred to his senior subordinate as his “old war-horse.”

Longstreet performed admirably in his new role. His I Corps delivered a crushing flank attack at Second Manassas; fought desperately along the Bloody Lane in Antietam, Maryland; and bloodily repulsed the Union assaults against the heights of Fredericksburg, Virginia, in 1862.

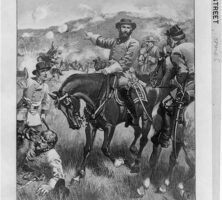

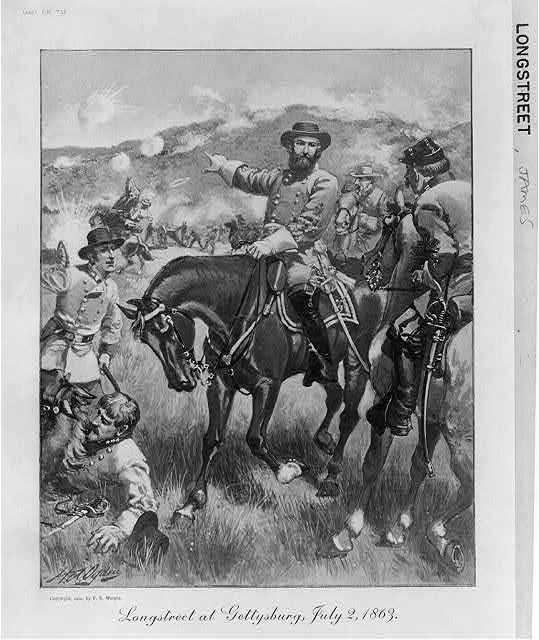

It was his actions at the Battle of Gettysburg, fought in Pennsylvania in July 1863, that haunted Longstreet after the war. For most of Lee’s first year in command, the Army of Northern Virginia possessed a highly effective command structure. Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson commanded the army’s II Corps and executed orders without much question. Longstreet’s role was often that of devil’s advocate, as he promoted caution and identified potential flaws in his aggressive commander’s plans. Gettysburg marked the first major campaign for the army without Jackson, who died in May 1863, and the beginning of problems within the army’s high command.

Lee’s refusal to fight defensively in Pennsylvania rankled Longstreet, who barely concealed his displeasure. Longstreet strongly disagreed with his superior’s tactics and behaved bitterly at Gettysburg. Still, his assault in the afternoon on July 2 virtually destroyed the Union army of the Potomac’s III Corps but failed to capture the prominent Round Tops that dominated the Union position. Lee refused to relinquish the initiative, however, and issued plans for a massive frontal assault on the Union center the following day. His subordinate so adamantly opposed the July 3 attack that he could only nod when asked if his men should advance. The abject failure of “Pickett’s Charge” was felt keenly throughout the Army of Northern Virginia and the Confederacy.

In the fall of 1863 Longstreet transferred to the West, where he played a decisive role in the Confederate victory at the Battle of Chickamauga in north Georgia. Upon his return to the eastern theater, his troops’ timely arrival on May 6, 1864, prevented Lee’s destruction in Virginia’s Wilderness. Amid the confusion of the battle, Longstreet was mistakenly wounded by his own men and forced out of duty for several months. When he returned, the army was already entrenched near Petersburg, Virginia. Lee’s surrender on April 9, 1865, ended Longstreet’s military career.

Republican Politician and Southern Pariah

Business, politics, and controversy marked Longstreet’s postwar career. With peace restored he moved to Louisiana, where he engaged in various business ventures, including the lucrative insurance and railroad industries. Controversy first swirled around Longstreet when he published a letter in a New Orleans newspaper advising acceptance of northern terms for Reconstruction in 1867. Although the letter advocated cooperation with the Republican Party in order to facilitate the restoration of the South’s traditional ruling class and to control African American voters, most of his southern peers flatly rejected any collaboration with Black Republicans.

His letter also laid the foundation for a campaign vilifying Longstreet after Lee’s death in 1870. A group of Virginians, led by Jubal A. Early, fabricated charges that Longstreet failed to execute Lee’s alleged order to attack at dawn on July 2, 1863, thereby costing the Confederates the victory at Gettysburg. Longstreet’s displeasure with Lee at Gettysburg became the basis for which Early and his cohorts attacked him, and the campaign also served to absolve Lee of any responsibility for the defeat.

Such criticism chafed Longstreet, but he was unable to defend himself well in writing. His continued Republican service only accentuated his image as the southern traitor. A warm friendship with U.S. president Ulysses S. Grant, however, helped Longstreet attain numerous patronage positions in New Orleans.

After a local newspaper invited the general to move his family to Gainesville, Georgia, Longstreet shifted his political support to his home state in 1875. He purchased the Piedmont Hotel in Gainesville, as well as a farm outside town—which his neighbors derisively called Gettysburg. Once back in Georgia he continued to hold minor political offices granted as thanks for his work on behalf of the Republican Party’s southern wing. Following a short stint as U.S. ambassador to Turkey that ended in 1881, Longstreet returned to Georgia and assumed the duties of U.S. marshal in Atlanta. Evidence of widespread corruption involving his deputies, however, led to his removal from that office in 1884.

Longstreet spent his final decades managing his farm and hotel, writing about the war, enjoying the camaraderie of Civil War reunions in spite of his tainted image, and spending time with his family. In 1889 his beloved wife of forty-one years, Maria Louisa Garland Longstreet, with whom he had several children, died. In 1897 he married Helen Dortch of nearby Carnesville, a woman more than forty years his junior. Longstreet, who was once told that he might not live a decade after being wounded in 1864, succumbed to pneumonia on January 2, 1904. He is buried in Gainesville’s Alta Vista Cemetery.