Lugenia Burns Hope was an early-twentieth-century social activist, reformer, and community organizer. Spending most of her career in Atlanta, she worked for the improvement of Black communities through traditional social work, community health campaigns, and political pressure for better education and infrastructure.

Early Life

Lugenia Burns was born on February 19, 1871, in St. Louis, Missouri, to Louisa M. Bertha and Ferdinand Burns, a successful carpenter. She was the youngest of seven children. Her family moved to Chicago, Illinois, after the death of her father, in the 1880s, well before the Great Migration of the early twentieth century. In Chicago she became involved in social work at two charity organizations, Kings Daughters and Hull House, founded by Jane Addams (who received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1931).

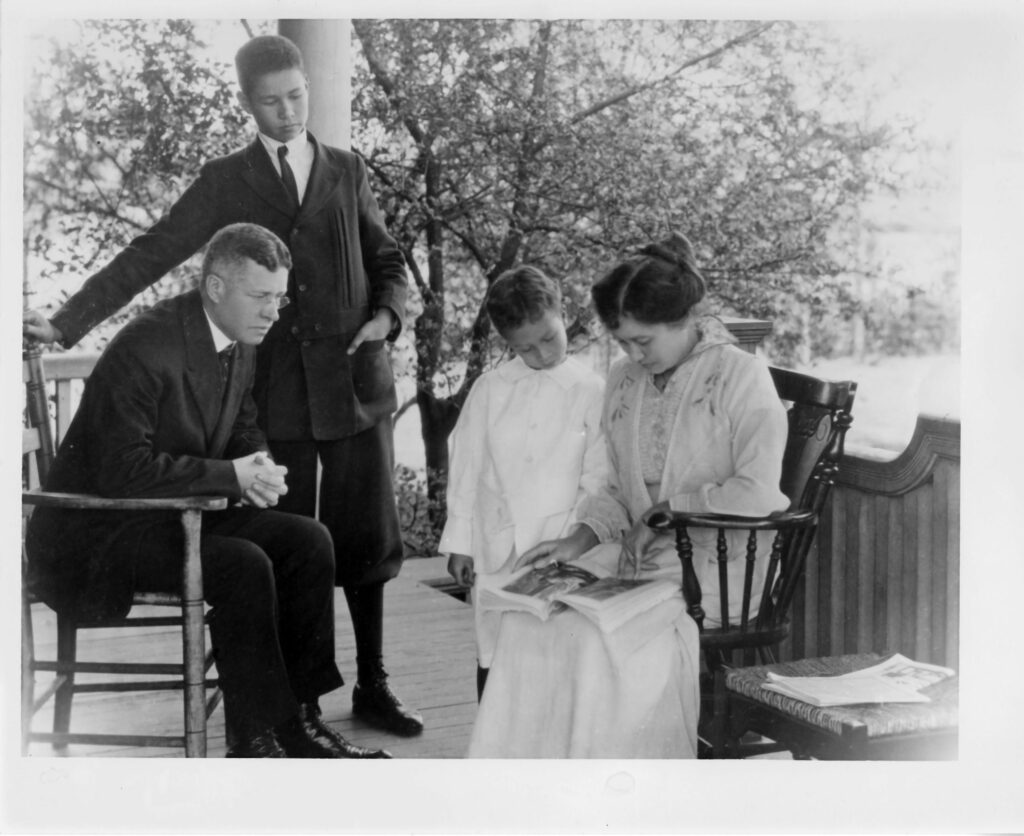

In 1893, at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, she met John Hope, a student at Brown University, in Providence, Rhode Island. The couple married in 1897 and moved to Nashville, Tennessee, where she worked in the community, teaching crafts and physical education, while her husband taught at Roger Williams University. The Hopes eventually had two sons, John and Edward. In 1898 the couple moved to Atlanta, and John began teaching at Atlanta Baptist College (later Morehouse College), becoming the school’s president in 1906.

Social Activism and Community Organizing

Atlanta

Noticing social decay in Atlanta’s Black neighborhoods, Lugenia Burns Hope, along with several other women, formed the Neighborhood Union in 1908. The group elected Hope, a commanding but calm and expert administrator, president. Despite her involvement in numerous organizations, she is most recognized for her leadership in the Neighborhood Union, which laid the groundwork for the grassroots component of the civil rights movement and became an international model for community building. Hope recruited Morehouse students to interview community members in order to assess their needs, and she quickly realized the extent to which Blacks in Atlanta suffered from a lack of sanitary homes and schools, medical and dental care, and recreational opportunities.

Under Hope’s leadership from 1908 to 1935, the Neighborhood Union carried out health education campaigns, demanded better conditions at schools, and sponsored arts and recreational activities for youth. In addition, the union “cleaned up” African American districts of characters they deemed morally undesirable, such as gamblers and prostitutes. Hope was more radical than her peers. In the era of Booker T. Washington, in which accommodation was more accepted than confrontation, she was headstrong and demanding. However, it was her social and economic position as the middle-class wife of a university professor that afforded her the authority to lead and to confront white institutionalized racism.

During World War I (1917-18) Hope became Special War Work Secretary for the YWCA’s War Work Council. She organized services for returning Black and Jewish soldiers and oversaw the training of hostess–house workers at Camp Upton in New York. Later on, as African American women became more involved with the YWCA, she challenged the organization’s discriminatory practices, calling for Black leadership of Black branches in the South.

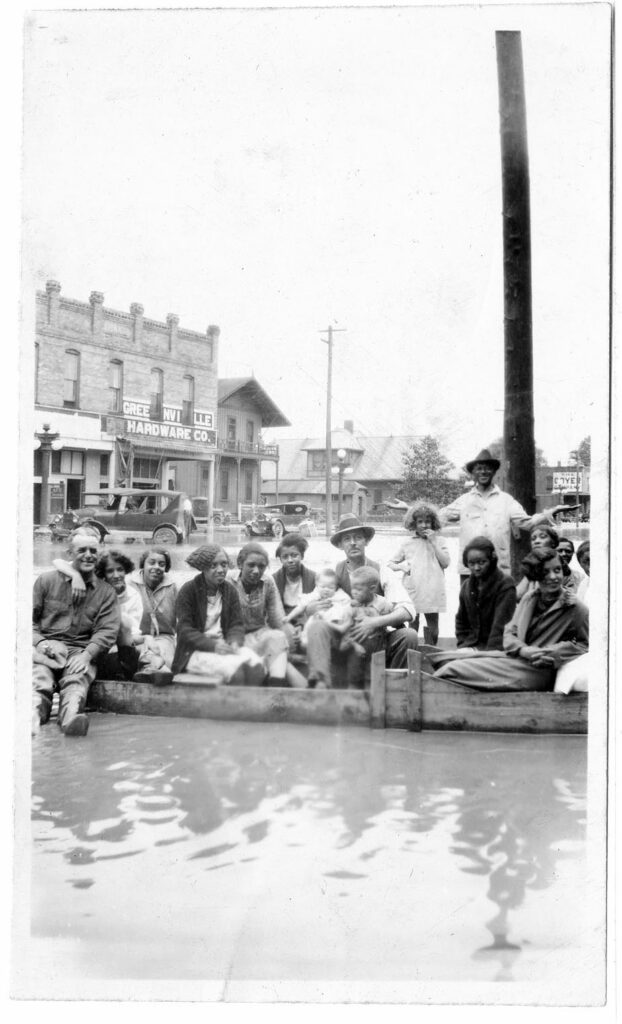

Following the Great Flood of 1927, which devastated much of Arkansas, Louisiana, and Mississippi, Hope was appointed to U.S. president Herbert Hoover’s Colored Advisory Commission. The commission, working with the American National Red Cross, concluded that African American victims of the flood had also been victims of discrimination during relief efforts. In 1932 Hope became the first vice president of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP)’s Atlanta chapter. During her tenure she oversaw the creation of “citizenship schools,” basic six-week courses that introduced African Americans to the role of government and civic participation. The campaign reached hundreds if not thousands of Atlantans.

New York

After her husband’s death in 1936, Hope moved to New York City. Conflict with the incoming Morehouse president may have played a role in her move. In 1937 she became an assistant to Mary McLeod Bethune, the director of Negro Affairs for the National Youth Administration, a New Deal program. She also continued to work for the NAACP, periodically visiting its headquarters in Washington, D.C.

Over the course of her career Hope was actively involved in a number of other organizations, including the Commission on Interracial Cooperation, the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs (in which she advocated for woman suffrage), the Association of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching, the National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses, and the International Council of Women of the Darker Races.

For periods at a time she lived with her niece Emma in Chicago, her son John in Nashville, and her other son Edward in Washington, D.C. She died on August 14, 1947, in Nashville, and her ashes were released from the tower of Morehouse College. She was inducted into Georgia Women of Achievement in 1996. Today, John and Lugenia Hope’s papers are housed in the Robert W. Woodruff Library of the Atlanta University Center.