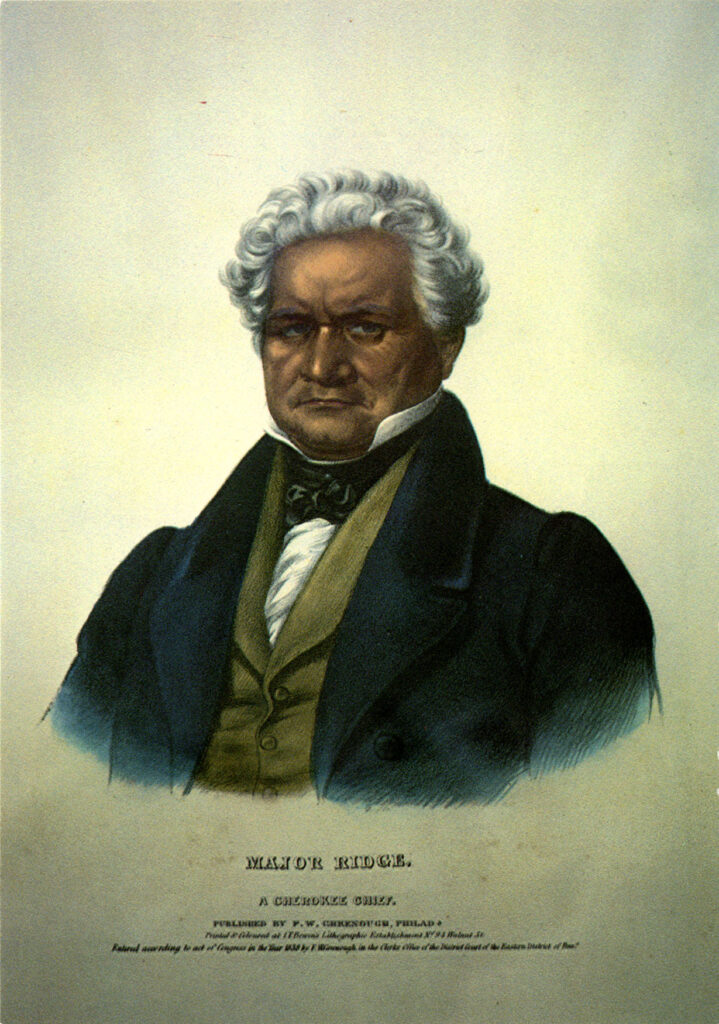

The Cherokee leader Major Ridge is primarily known for signing the Treaty of New Echota (1835), which led to the Trail of Tears. Before this tragic period in Cherokee history, however, he was one of the most prominent leaders of the Cherokee nation.

Major Ridge was born in the early 1770s in Tennessee. His Cherokee name, Kah-nung-da-tla-geh, means “the man who walks on the mountaintop.” Englishmen called him “The Ridge.” He was brought up as a traditional hunter and warrior, resisting white encroachment on Cherokee lands. He married a fellow Cherokee, Susanna Wickett, in the early 1790s, and they moved to Pine Log, in present-day Bartow County.

As a result of U.S. president George Washington’s “civilization” policy for Native Americans, the government agent Benjamin Hawkins provided The Ridge with new farm implements and Susanna with a spinning wheel and loom, so that the young couple could learn “white” ways of working. (Traditionally, Cherokee women farmed, and the men hunted, fished, conducted politics, and fought wars.) With his military experience and brilliant command of the Cherokee language, The Ridge soon became a successful politician. Purchasing enslaved Africans to work as field laborers enabled the Ridge family to enlarge their agricultural production to plantation status.

When the War of 1812 (1812-15) began, The Ridge joined General Andrew Jackson’s forces in fighting the Creeks and the British in Alabama. For his heroic leadership at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend, The Ridge received the title of major, which he subsequently used as his first name.

After the war, the Ridge family established a plantation on the Oostanaula River in present-day Rome. With his friend and neighbor John Ross, Ridge helped establish a Cherokee Nation with three branches of government in 1827. He served as counselor, and Ross became principal chief, the equivalent of president.

Believing that they had succeeded in the “civilization” process by establishing a government on a U.S. model, Cherokees like the Ridges were shocked when the U.S. Congress passed the Indian Removal Bill of 1830 and Georgia implemented a lottery to dispense Cherokee lands shortly thereafter. As Georgians began to move illegally into the Cherokees’ houses, businesses, and plantations, often by force, Ridge became convinced that either warfare or negotiation with the U.S. government must proceed. He became a leader of the Treaty Party, which favored removal to Indian Territory west of the Mississippi River (in present-day Oklahoma), in exchange for financial compensation of $5 million to the Cherokees. He and a minority of Cherokees signed the Treaty of New Echota in December 1835 without authorization from Ross or the Cherokee government. The illegal treaty was then signed by President Jackson and passed by one vote in the U.S. Senate.

The Ridge family and others voluntarily moved west, but Principal Chief Ross and opponents of the treaty fought its implementation. They failed, and Cherokee removal was forced by the military. Because of harsh weather conditions, more than 4,000 Cherokees died during the 1838-39 winter on the “trail where they cried,” commonly known as the Trail of Tears. On June 22, 1839, in retaliation for Ridge’s part in this tragedy, some of Ross’s supporters ambushed and killed Ridge on his way into town from his plantation on Honey Creek in Indian Territory. His assailants were never officially identified or prosecuted.

Ridge’s grandson John Rollin Ridge would be known as the first Native American novelist.