Georgians have always had the poor in their midst. But from the inaccurate story of original settlement of the colony by inmates of debtors’ prisons in England to the modern depictions of such writers as Margaret Mitchell, Flannery O’Connor, Erskine Caldwell, and James Dickey, the prevalence and depth of poverty are often exaggerated. Still, many of Georgia’s early settlers were poor people seeking a better life. Many found it; some did not. As in the rest of the country, hardscrabble farms and rough frontier were fertile ground for poverty, and slums grew rapidly in urban areas as well. By the 1850s grim tenements for desperate Irish immigrants existed in Savannah, just as in Boston, Massachusetts, and New York City.

Although enslaved African Americans fared the worst by far, some poor whites faced intensely dire economic conditions. The disruptions of the Civil War (1861-65) and Reconstruction mired Black Americans in a new sort of poverty and dragged many more whites into a similar abyss. Sharecropping and tenant farming trapped families for generations, as did emerging industries, which paid low wages and imposed company-town restrictions. Once-proud yeomen frequently became objects of ridicule, and sometimes they responded angrily and even viciously, often taking vulnerable Blacks as their targets. Financially “poor whites” were increasingly labeled “poor white trash” and worse. The terms, “cracker,” “hillbilly,” “clay eater,” “linthead,” “peckerwood,” “buckra,” and especially “redneck” only scratched the surface of their rejection and slander.

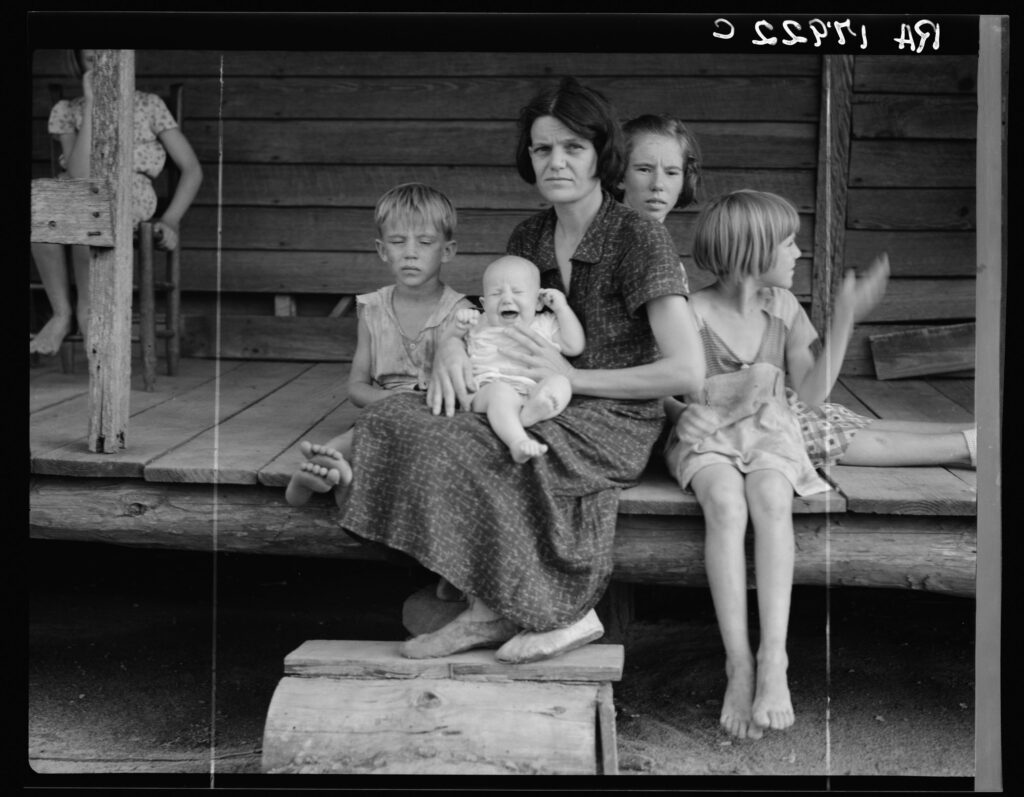

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Northerners and foreigners played this game, but the greatest hostility to poor whites came from their fellow southerners, sometimes Blacks but more often upper-class whites. Not all white elites shared the general contempt for the poor. Before the Civil War Augustus Baldwin Longstreet sketched the foibles of ordinary, unpolished Georgians with humor, understanding, and even affection. Richard Malcolm Johnston’s Georgia Sketches and Charles H. Smith’s “Bill Arp” stories performed a similar service, but perhaps the most sensitive portrayal of poor whites in antebellum Georgia came in Caroline Miller’s 1934 Pulitzer Prize–winning novel, Lamb in His Bosom, which described the struggle for existence on subsistence farms in the isolated wiregrass region of southeastern Georgia. In her heroes and heroines Miller saw her ancestors: plain, simple men and women who barely survived but never wavered and passed life and hope on to the next generation.

Generally, the view of poor white southerners grew more and more negative, especially in modern mass market movies and television programs, which have often stressed the negative and grotesque. Georgia has borne its full share of this stereotype of lower-class southern whites who share poverty status with immigrants, Blacks, and other minorities.

Although the stereotype of the poor white southerner in the early twentieth century, as portrayed in popular media, was exaggerated, the problem of poverty was very real. The national mobilization of troops in World War I (1917-18) invited comparisons between the South and the rest of the country. Southern and Georgia whites had less money, less education, and poorer health than white Americans in general. Only Black southerners had more handicaps. In the 1920s matters became worse when the boll weevil devastated the South’s cotton culture and its economy.

Although the Great Depression of the 1930s shook the whole national economy to its foundations, U.S. president Franklin D. Roosevelt isolated the already depressed South as an especially desperate economic problem. Erskine Caldwell, particularly in his phenomenal best-selling novels, Tobacco Road (1932) and God’s Little Acre (1933), provided the most indelible impressions of rural poverty in the South and continued to do so in both stage and screen versions. Harry Crews’s autobiography of his early days as part of a sharecropping family in Bacon County in southeastern Georgia, entitled A Childhood: The Biography of a Place (1978), is an equally poignant depiction of white poverty in the 1930s, as is Rick Bragg’s Ava’s Man (2001), a portrait of Bragg’s maternal grandfather and his children in and around Floyd County in the northwestern corner of the state.

World War II (1941-45) began the great economic revival for Georgia and the South. In and out of the armed forces, unskilled southern whites, and many African Americans as well, were trained for industrial and commercial work they had never dreamed of attempting, much less mastering. Military camps grew like mushrooms, especially in Georgia, and big industrial plants began to appear across the once rural landscape. Soon, blue-collar families from every nook and cranny of old Georgia found their way to white-collar life in metropolitan areas like Atlanta. By the 1960s Blacks had begun to share in this progress, but not all rural Georgians were beneficiaries of this recovery. Janisse Ray’s Ecology of a Cracker Childhood (1999) describes her upbringing in a junkyard in Baxley in the 1960s and 1970s and the ways in which her family coped with the poverty that shaped their lives.

Such works remind us that although the late twentieth century was a time of unprecedented prosperity for Georgia, poverty is still endemic. Inadequate public schools, disintegrating families, high crime rates, urban decay, drugs, and many other problems present obstacles for many Georgians, but the old curse of poverty no longer seems inescapable.