In the context of southern politics, the term Redemption refers to the overthrow or defeat of Radical Republicans (white and Black) by white Democrats, marking the end of the Reconstruction era in the South. In addition to its biblical allusions, the term also underscores the widely held belief among white southerners of that era that the Republican state regimes that ruled during Reconstruction had been inefficient and corrupt, and that the “Redeemers” who reestablished white Democratic control of the state also restored effective and honest government. In recent years historians have come to avoid the term because of both the bias it suggests and the very different way in which modern scholars interpret the overthrow of Reconstruction.

Courtesy of Georgia Capitol Museum, University of Georgia Libraries

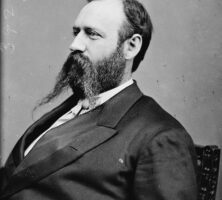

In Georgia, Redemption became complete when Governor James M. Smith took office in January 1872. To an even greater extent than in other southern states, Redemption in Georgia ushered in a long period of Democratic dominance in state politics: for the next 131 years, every governor of Georgia would be a Democrat.

Efforts to Undermine Reconstruction

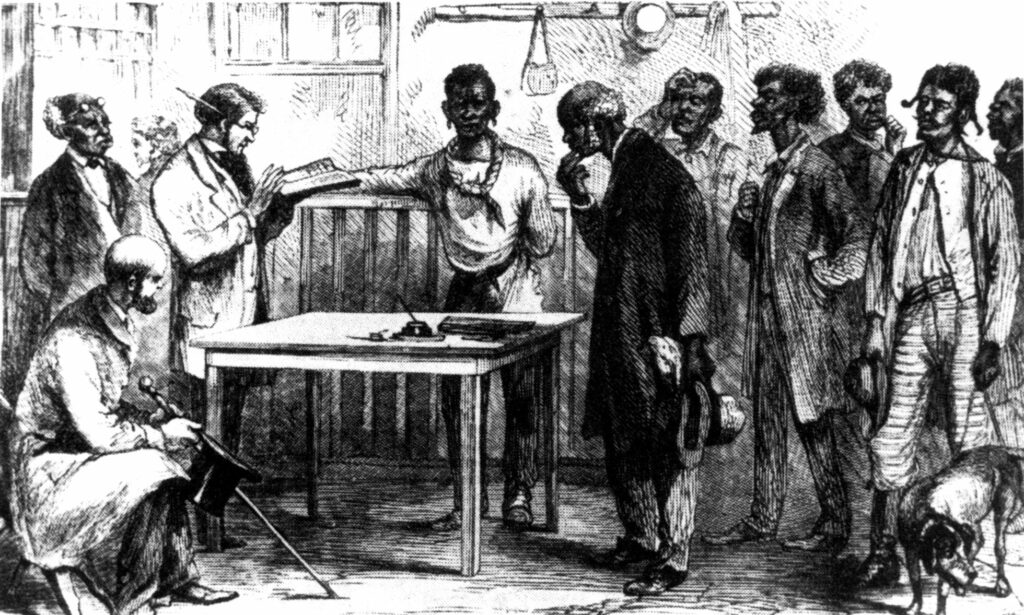

Under the terms of the federal Reconstruction Acts passed by the U.S. Congress in 1867, Georgia adopted a new state constitution granting Black suffrage in 1868 and held an election for state officers and congressmen. Republican Rufus Bullock defeated Democratic candidate John B. Gordon, and the Republicans won control of the state legislature. White Democrats wasted little time, however, in trying to undermine Republican power and Black political activism in particular. The Ku Klux Klan waged a campaign of intimidation and violence against Republicans, especially African Americans, and the Freedmen’s Bureau reported that thirty-one Blacks were murdered in Georgia during the three months preceding the national elections of 1868.

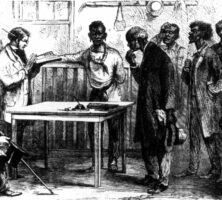

From Harper's Weekly

On September 19, 1868, in the small Mitchell County town of Camilla, a white mob attacked a predominantly Black group of Republicans who were coming into town to hear a congressional candidate speak. The attack, which became known as the Camilla Massacre, left between nine and thirteen African Americans dead (sources differ on the exact number). Earlier in the month, the state legislature had expelled all twenty-eight legislators who could be definitely established as being of at least “one-eighth Negro blood.”

Such acts of open defiance against both the spirit and the letter of the Reconstruction Acts led Congress to suspend Georgia’s representation and reinstitute military rule in the state. Military commander General Alfred H. Terry removed twenty-nine white Democrats from the state legislature, most of whom were replaced by the African American Republicans who had been expelled. In February 1870 Georgia ratified the Fifteenth Amendment, and five months later Congress once again restored Georgia to the Union.

The Triumph of the Redeemers

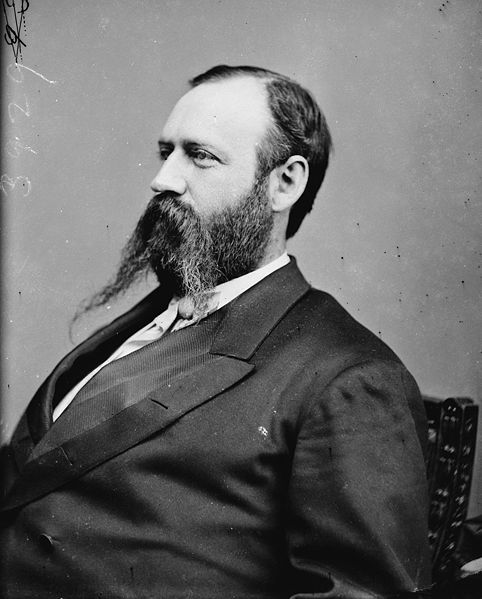

“Redemption” truly began in Georgia with the state elections held in December 1870. By then the state Republican Party suffered from internal divisions and from charges of wastefulness and corruption, which, while greatly exaggerated by Democratic politicians and newspapers, nevertheless bore some truth. Democrats won control of both houses of the state legislature, and in late October 1871, just before the newly elected legislators took office, Governor Bullock resigned and fled the state. Republican Benjamin Conley, president of the state senate, succeeded Bullock, but the new legislature passed a law (overriding Conley’s veto) that a special election be held in December 1871 to choose a new governor. Republicans boycotted the election and did not put forth a candidate. Democrat James M. Smith won the no-contest special election, and he went on to win the March 1872 general election in a landslide victory over Republican Dawson Walker.

Photograph by Wikimedia

Results of Redemption

The Democrats’ “redemption” of Georgia marked the end of Reconstruction in the state and the beginning of Georgia’s long reign as one of the most Democratic states of the “Solid South.” Redemption also marked the beginning of eighteen years of political dominance by the state’s so-called Bourbon Democrats and the Bourbon Triumvirate of Joseph E. Brown, Alfred H. Colquitt, and John B. Gordon. During this period the state government promoted the interests of planters and businessmen over those of small farmers and laborers, including sharecroppers, while doing virtually nothing to protect the interests of Black citizens. The resulting widespread dissatisfaction on the part of small farmers and laborers of both races would lead to the first serious challenge to Democratic rule in post-Reconstruction Georgia: the Populist revolt of the 1890s.