The Southern Comfort Conference was one of the most well-known transgender conferences in the United States. Originally held in Atlanta, it created a space where members of the transgender community could gather, learn about medical resources, and organize politically.

In 1990 members of the International Foundation for Gender Education and transgender advocacy groups based in the southeastern U.S. began planning for a new regional conference to be held in Atlanta the following year. The event would be particularly important for fostering community in the South since group gatherings provided some of the only spaces where trans people could express themselves openly and safely in numbers.

From the start, Southern Comfort was known for its inclusivity. In addition to the participation of a wide variety of transfeminine people, the active inclusion and even leadership of transmasculine individuals at Southern Comfort distinguished the Atlanta conference from its contemporaries. In 1999 it promised that “if transgender is an issue in your life, you are welcome!”

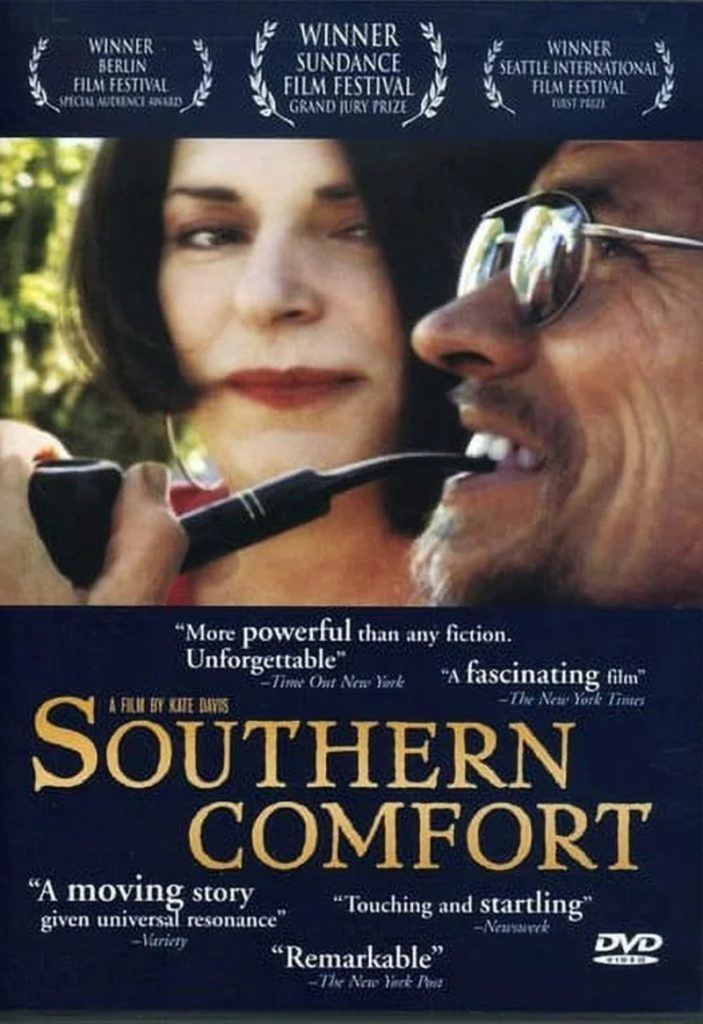

The 2001 documentary Southern Comfort brought the conference unprecedented attention and visibility, marking the beginning of a period of attendance growth during the 2000s. Directed by Kate Davis, the film follows the final months of long-time conference regular Robert Eads, a Georgian transgender man dying of ovarian cancer with his transfeminine partner Lola Cola by his side. The documentary chronicles their panel on intimacy for transgender couples and Eads’s farewell speech to the conference attendees. It portrayed “SoCo,” as attendees called the conference, as a place of refuge far away from the medical discrimination that prevented Eads from receiving cancer treatment. After winning a Grand Jury Prize at the 2001 Sundance Film Festival, the film’s critical acclaim brought the conference national attention outside of transgender circles.

With receptions, makeover sessions, and trips to Atlantan landmarks like the High Museum of Art, Southern Comfort offered attendees an opportunity to both socialize and learn. Seminars took up much of the conference’s daytime schedule. Healthcare providers, usually endocrinologists and surgeons, explained the latest advancements in hormone therapies and surgeries. Other talks focused on addressing the emotional and spiritual needs of attendees. The healthcare needs of transgender men gained more attention after the death of Eads. Conference organizers created a partnership with healthcare providers, later named after Eads, to offer free or low-cost gynecological exams. Activism for transgender rights also maintained a presence in the conference. Over the years the conference served as a meeting and organizing space for advocacy organizations like the International Foundation for Gender Education and the National Center for Transgender Equality.

Throughout the 2000s and early 2010s, Southern Comfort cemented its status as a prominent transgender conference and held the title of the largest transgender convention in the United States as early as 2007. The Human Rights Campaign (HRC) participated in the 2007 conference, co-sponsoring the nation’s first Transgender Career Expo. As part of their participation, HRC president Joe Solmonese promised to only support the federal Employment Non-Discrimination Act if it included transgender people. Southern Comfort attendees and much of the broader transgender community thus felt betrayed when the HRC supported the doomed bill even after the removal of protections on the basis of gender identity. Seven years later, Southern Comfort was also the platform that HRC president Chad Griffin used to formally apologize to the transgender community for abandoning them in 2007, promising greater inclusion in anti-discrimination efforts in employment, housing, and education. In another milestone, Southern Comfort hosted a joint symposium with the World Professional Association for Transgender Health in 2011. It created dialogue between transgender patients and medical professionals as the organization revised its official Standards of Care protocols. Southern Comfort continued to prioritize inclusivity during this period, organizing events and seminars for trans people of color starting in 2003 and the first “family day-conference” exclusively for trans kids and teens in 2014.

After two decades in Atlanta, the conference faced declining attendance and moved to Fort Lauderdale, Florida in 2015. The move was short-lived as the conference announced its closure in 2016 after a costly lawsuit required they switch to a new but unaffordable insurance. Organizers managed to revive the event in 2019 but it was suspended once again the following year due to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. After a nationwide wave of legislation restricting drag performances, medical transition, and transgender inclusion in public spaces beginning in 2021, events like Southern Comfort became much harder to host, and subsequent efforts to organize a conference of SoCo’s scale have been unsuccessful.

While no transgender conference of Southern Comfort’s size and scope has been consistently held in Atlanta since its departure, the conference’s distinct atmosphere of a large “transgender family” gathering is remembered through the Southern Comfort documentary.