The battle between ship and shore on the coast of Confederate Georgia was a pivotal part of the Union strategy to subdue the state during the Civil War (1861-65).

U.S. president Abraham Lincoln’s call at the start of the war for a naval blockade of the entire Southern coastline took time to materialize, but by early 1862, under Union general Winfield Scott’s “Anaconda Plan,” the Union navy had positioned a serviceable fleet off the coast of the South’s most prominent Confederate ports. In Georgia, Union strategy centered on Savannah, the state’s most significant port city. Beyond Savannah, Union forces generally focused on securing bases of operation on outlying coastal islands to counter Confederate privateers.

Confederate defensive strategy, in turn, evolved with the Union blockade. After the fall of Port Royal, South Carolina, in November 1861, Confederate president Jefferson Davis appointed General Robert E. Lee to reorganize Confederate coastal defenses. Lee quickly realized the impossibility of defending the entire coastline and decided to consolidate limited Confederate forces and materiel at key strategic points. He countered Union naval superiority by ensuring easy reinforcement of Confederate coastal positions along railroad lines. In this way, Lee minimized reliance upon the fledgling Confederate navy and maximized the use of Confederate military forces in coastal areas, including both Georgia’s Sea Islands and mainland ports with railroad connections.

Confederate Privateering and Naval Innovation

On the night of November 11, 1861, a daring Confederate blockade-runner, Edward C. Anderson, escaped under Union eyes and piloted his ship, the Fingal, into the port of Savannah. A native of Savannah, Anderson was the first of many who attempted to assist the Confederate cause by breaking through the Union’s extensive coastal blockade, which stretched from Virginia to Florida. However, in Georgia none would match Anderson’s success. The landing of Enfield rifles and cannons, as well as sabers and military uniforms, at the state’s major port marked the high tide of the South’s ability to penetrate the North’s naval forces stationed along the Georgia shore.

But Anderson’s remarkable feat also signaled to the Union that it needed to bolster its blockade and close off access to Savannah, which, like Charleston, South Carolina, to the north, offered an access point readily able to provide Confederate armies with necessary war materiel. If the Union hoped to wear the South down by cutting it off from the outside world, then it had to put a stop to incidents like the Fingal’s arrival at Savannah.

While smaller vessels than the Fingal sometimes did evade Northern capture, their modest hauls made for paltry victories. Because Union forces took control of the seas around Brunswick and St. Simons Island in the war’s beginning stages, the virtual closing of Savannah’s port to privateers like Anderson greatly contributed to eventual Union success in Georgia.

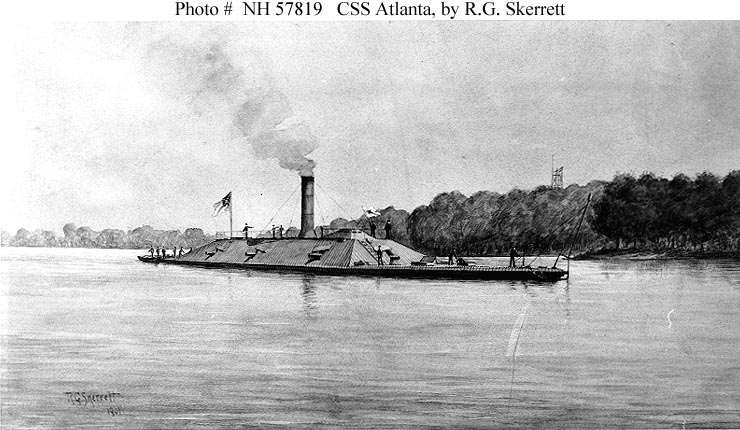

Confederate leadership and the people of Savannah came to pin their hopes of resisting Union occupation and breaking the blockade on a handful of gunboats. While built as a British merchant ship, the blockade-running Fingal was converted to an ironclad in 1862 and renamed the Atlanta. This ship, as well as the Georgia and later the Savannah, were ironclads patterned after the CSS Virginia, famous for its battle against the USS Monitor at Hampton Roads, Virginia, in 1862. The Macon, the Sampson, the Resolute, and the Isondiga, wooden gunboats of varying designs, constituted the remainder of the Confederate fleet in Savannah. In addition, Georgia’s coastal defenses included innovative torpedoes, developed by Commodore Matthew Maury, which caused the Union navy periodic concern. Despite these innovations, the Confederate naval forces paled in comparison to Union naval strength. Despite fleeting successes by Southern naval forces, the increasingly potent Union navy ultimately enabled complete Union control of the Georgia coastline.

Fort Pulaski and Savannah Harbor

General Lee’s decision to consolidate forces in 1862 began with the withdrawal of Confederate troops from St. Simons and Jekyll islands on the southeastern Georgia coast. On March 9, 1862, two Union gunboats arrived to find abandoned the earthwork batteries overlooking the channel between the islands. Sailing farther inland to the town of Brunswick, the ships found the town deserted and the wharf and depot ablaze.

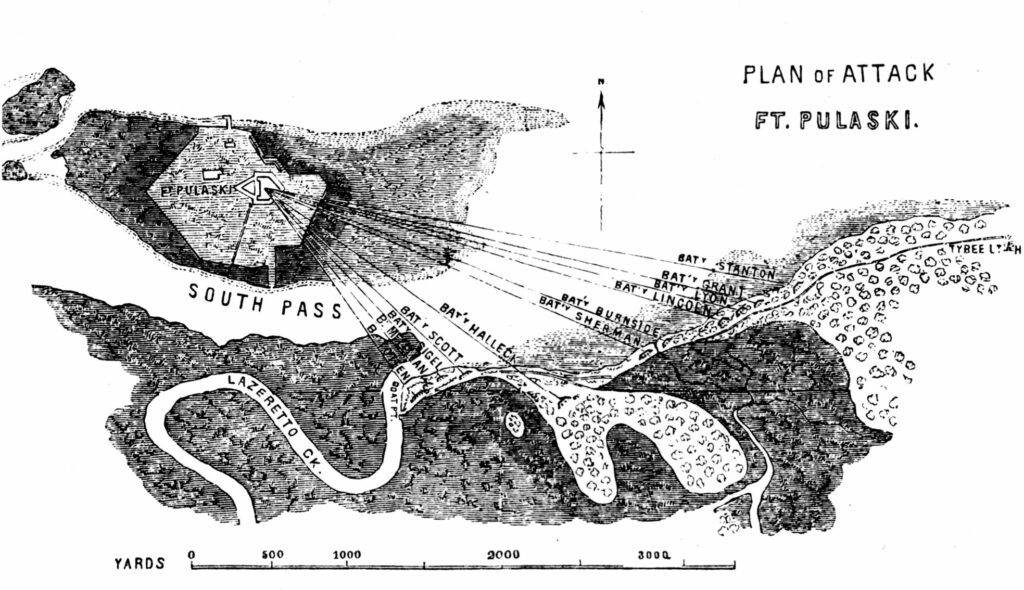

Union naval forces took other Sea Islands with similar lack of resistance. Tybee, the northernmost of Georgia’s islands and within easy range of Fort Pulaski, fell to Union forces without a fight. Along with Union gunboats, batteries erected on Tybee initiated the first major engagement in Savannah on April 10, 1862. Union forces under the command of Major General David Hunter and Captain Quincy A. Gillmore bombarded Fort Pulaski, which was commanded by Confederate colonel Charles H. Olmstead, overnight. The rifled cannons of the Union gunboat Norwich, as well as those from the land batteries, made short work of the masonry walls of Fort Pulaski. Fearing a complete breach in the walls and explosion of the fort’s powder magazine, Olmstead surrendered. Union troops occupied Fort Pulaski for the remainder of the war.

Early in the war, 1,500 Confederate troops were ordered to St. Simons Island to defend it against the Union blockade. By the end of 1862 Lee had ordered those troops to move north to help defend Savannah, leaving St. Simons open to Union occupation. In June 1863 the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts regiment, one of the Union’s first African American regiments, under commander Robert Gould Shaw, spent several weeks on the island and made an expedition up the Altamaha River. On June 11 they were ordered to attack the nearby port of Darien, which was thought to be a base for blockade-running activity. Despite objections from Shaw, his troops, along with the Second South Carolina Infantry, burned and looted the town, causing the greatest wartime destruction to civilian property along the Georgia coast. The film Glory (1989) recreates this incident, along with the Fifth-fourth’s suicidal assualt on Fort Wagner, South Carolina, on July 18, 1863.

Fort McAllister and Savannah’s Surrender

Two years passed before Union troops moved on Savannah itself, and contrary to Confederate expectations, the assault came from the west, not the east. Savannah’s other protective bastion, Fort McAllister, to the city’s south on the Ogeechee River, became its last remaining hope and a primary obstacle to Union forces.

Several naval sorties engaged Fort McAllister throughout 1862 and 1863. On July 29, 1862, four Union gunboats bombarded the fort for several hours, accomplishing little. Again, on November 19, three ships assailed the fort to little avail. On January 27, 1863, the Union ironclad Montauk and several wooden gunboats pounded the fort for several hours, again with little result. Similar engagements occurred on February 1, 27, and 28. In the last engagement, Union forces failed to drastically affect Fort McAllister but destroyed the Confederate privateer Nashville, which had grounded near the fort in seeking protection from Union ships. Another bombardment of the fort three days later again produced minimal results. These repeated repulsions of the Union navy by Confederate troops in Fort McAllister accomplished little for the Northern cause but heartened the Confederate troops, as well as the citizens of Savannah.

Drawing on this confidence, Confederate flag officer Josiah Tattnall sought to employ his ironclads to break through the Union blockade in Savannah’s harbor. However, several ill-fated attempts to engage Union forces ultimately resulted in the loss of the ironclad Atlanta at the hands of the Union ironclad Weehawken on June 17, 1863. Though a new ironclad, the Savannah, became operational in July, along with two wooden gunboats, the Macon and Sampson, Confederate leadership in Savannah generally spurned offensive operations for the remainder of the war.

Nevertheless, in June 1864 Confederate naval troops managed a minor victory with the capture of the USS Water Witch. While anchored near Savannah, the Water Witch was captured by officers and crew members of the Georgia, Savannah, and Sampson. Ultimately, however, that small conquest did not improve the Confederacy’s fortunes.

This increasingly defensive stance culminated in facing Union general William T. Sherman’s troops on their 1864 march to the sea. Fort McAllister formed the backbone of Savannah’s remaining defensive line. Late in the afternoon of December 13, 1864, a Union division under Brigadier General William B. Hazen, part of Sherman’s Fifteenth Corps, assaulted McAllister. Though slowed by obstacles and minefields, in addition to Confederate artillery fire, the Union troops overwhelmed the fort and forced its surrender.

With McAllister occupied, Sherman effectively linked with the Union navy, sounding the death knell for Confederate Savannah. The Confederate leadership realized the hopelessness of the situation following McAllister’s capture and withdrew their remaining forces across the Savannah River into South Carolina. In retreat, the Confederates set fire to their surviving naval squadron, including the ironclad Savannah, effectively ending any resistance to Sherman’s capture of the city. In a telegram dated December 22, 1864, General Sherman presented the city of Savannah as a Christmas gift to President Lincoln, ending both the March to the Sea and major military engagement on the Georgia coast.