William Calley Jr. was the only U.S. soldier involved in the 1968 My Lai Massacre to be court-martialed and convicted of murder. During the My Lai Massacre, U.S. troops killed hundreds of unarmed civilians in a small coastal village in Qiang Ngai province, South Vietnam. As the Vietnam War (1964-73) drew to a close, Calley’s name became a byword for the conflict’s brutality and for the ways the war divided the American public.

Early Life

William Laws Calley Jr. was born to an affluent family in Miami, Florida, on June 8, 1943. An indifferent student, Calley dropped out of Palm Beach Junior College after one semester and worked a series of jobs before enlisting in the army. He was admitted to the army’s Officer Candidate School in 1967 at Fort Benning (renamed Fort Moore in 2023) and received a commission as a first lieutenant shortly thereafter. The army, short of officers near the height of the Vietnam War, appointed Calley to command First Platoon, Charlie Company in the Americal Division, which was cobbled together from smaller units of other divisions.

My Lai Massacre

On March 16, 1968, Charlie Company entered a Vietnamese village that the army designated My Lai 4 in Qiang Ngai province, a region on the northeastern coast of what was then South Vietnam. Expecting to find a group of Vietcong (South Vietnamese guerrillas fighting the U.S. and South Vietnamese on behalf of the North Vietnamese Communist regime), the Americans instead found women, children, and elderly men preparing their breakfast. Recollections of what happened next vary in their precise details, but Charlie Company’s actions would come to be known as the My Lai Massacre. Supported by artillery and helicopter units, and under vague orders from superiors to undertake a scorched earth policy against the Vietcong, the American troops laid waste to the village and indiscriminately murdered villagers, stacking hundreds of bodies in ditches along the side of the road.

All three platoons participated in the killing, but witnesses remembered Calley’s role in detail. Charlie Company’s task force log for March 16, 1968, later submitted to the Department of the Army Review of the Preliminary Investigations into the My Lai Incident (known as the Peers Commission), showed that Calley’s platoon landed at 7:30 a.m. in nine troop helicopters accompanied by two helicopter gunships. By 7:35 a.m., the first Vietnamese civilian had been killed; by 8:40 a.m., My Lai 4 was in ruins. In the midst of the massacre, Chief Warrant Officer Hugh Thompson of Stone Mountain, flying a scout helicopter in support of Charlie Company, spotted Calley in action and landed his aircraft to prevent Calley and his troops from continuing the killing. Thompson saw Calley approach a group of women and children, and told Calley he would fly the civilians to safety. Calley then threatened Thompson with a hand grenade, but he relented when another helicopter landed in support of Thompson.

In the end, the Peers Commission concluded that Calley’s platoon was responsible for roughly one-third of the deaths at My Lai 4. Estimates vary on the total number killed; the army’s Criminal Investigation Division puts the figure at 347 people, while the Vietnamese government’s figure of 504 includes those killed in a neighboring hamlet.

Cover-Up and Trial

After the massacre, officials in both the military and the Nixon administration attempted to prevent news of the massacre from reaching the press. But in 1969, the investigative journalist Seymour Hersh interviewed Calley at Fort Benning, where the court-martial was held, and wrote a widely circulated story about the incident. He laid less personal blame on Calley than the army, citing other forces that led to the tragedy: the low quality of Americal Division’s officer corps; unclear orders from the Americal’s commander, Major General Samuel Koster, and his subordinates; mission assignments that stressed body counts over clear objectives; anxiousness about the guerrilla tactics of the Vietcong; and a culture of impunity with respect to murder, rape, and looting. Hersh would later receive the Pulitzer Prize for his reporting.

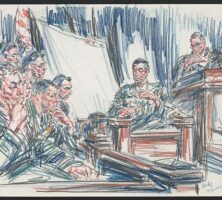

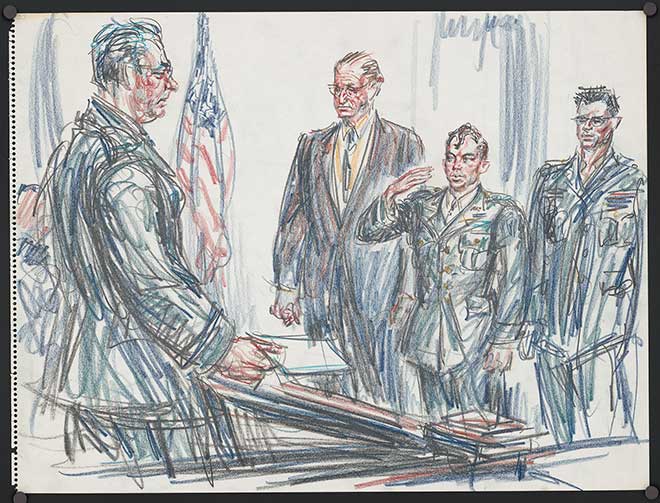

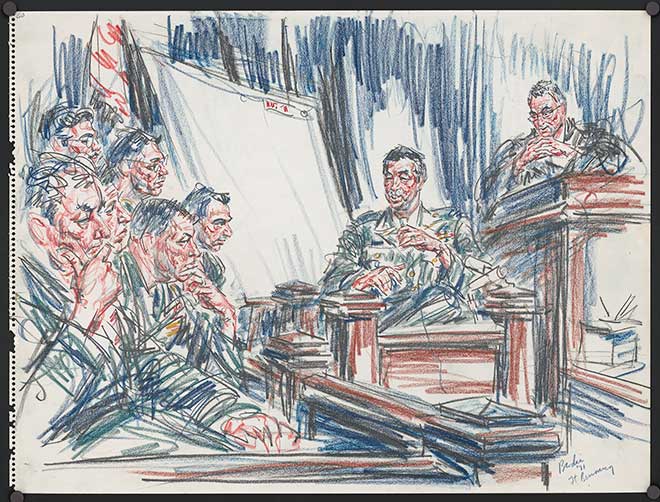

With the press now aware of the massacre, Calley’s court-martial proceedings became high profile national news. The army originally charged twenty-five officers and enlisted men with crimes at My Lai or offenses related to the cover-up. Though two other officers were demoted, only Calley was convicted.

After four months of proceedings, Calley was found guilty on twenty-two counts of premeditated murder and sentenced to life in prison. In the meantime, a “Free Calley” movement developed, and Calley’s supporters insisted that the lieutenant had taken the fall for crimes which were really the outgrowth of an unjust and unwise war.

Amidst the outcry, President Nixon intervened. He first ordered Calley be taken from the army stockade at Fort Benning and placed under house arrest; Secretary of the Army Howard Callaway then granted Calley clemency and commuted his sentence twice—first to twenty years, then to ten. Calley was released on bail after just under four years of house arrest, and his sentence was commuted to time served on procedural grounds.

Later Life and Apology

In the years after his release, Calley settled in Columbus, Georgia, where he married Penny Vick and began working at her father’s jewelry store. Journalists occasionally came to Columbus to ask for an interview, but Calley said little. When he did speak about his role at My Lai, he insisted he had simply been following orders and was not haunted by his actions.

On August 20, 2009, at the age of sixty-six, William Calley Jr. apologized for his role at My Lai. Speaking before the Kiwanis Club in Columbus, Georgia, just a few miles from Fort Benning, Calley expressed regret for the civilians he killed in Qiang Ngai province. “There is not a day that goes by that I do not feel remorse for what happened that day at My Lai,” he said, “I feel remorse for the Vietnamese who were killed, for their families, for the American soldiers involved and their families. I am very sorry.” He added: “I did what they say I did,” but he maintained, just as he always had, that he had only been following orders.