The Yazoo land fraud was one of the most significant events in the post–Revolutionary War (1775-83) history of Georgia. The bizarre climax to a decade of frenzied speculation in the state’s public lands, the Yazoo sale of 1795 did much to shape Georgia politics and to strain relations with the federal government for a generation.

Georgia was too weak after the Revolution to defend its vast western land claims, called the “Yazoo lands” after the river that flowed through the westernmost part. Consequently, the legislature listened eagerly to proposals from speculators willing to pay for the right to form settlements there. In the 1780s the state supported two unsuccessful speculative projects to establish counties in the western territory and in 1788 tried, again without success, to cede a portion of those lands to Congress. In 1789 the legislature sold about 25 million acres to three companies, only to torpedo the sale six months later by insisting that payment be made in gold and silver rather than in depreciated paper currency.

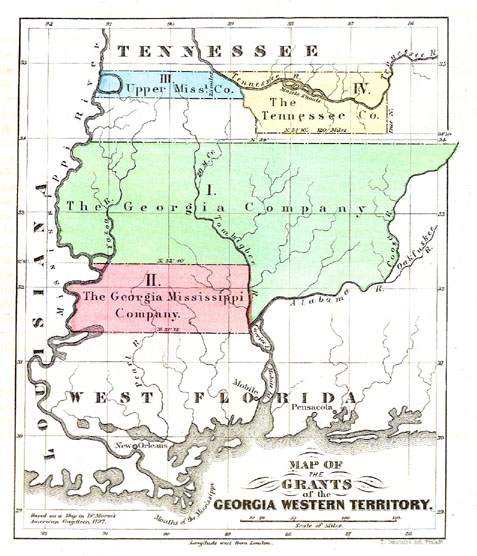

Pressure to act continued to build on legislators until, by mid-November 1794, a majority reportedly favored the sale of the western territory. On January 7, 1795, Georgia governor George Mathews signed the Yazoo Act, which transferred 35 million acres in present-day Alabama and Mississippi to four companies for $500,000. To achieve this successful sale, the leader of the Yazooists, Georgia’s Federalist U.S. senator James Gunn, had arranged the distribution of money and Yazoo land to legislators, state officials, newspaper editors, and other influential Georgians. Cries of bribery and corruption accompanied the Yazoo Act as it made its way to final passage. Angry Georgians protested the sale in petitions and street demonstrations. Despite the swelling opposition, the Yazoo companies completed their purchases.

Learning of the circumstances surrounding passage of the Yazoo Act, Georgia’s leading Jeffersonian Republican, U.S. senator James Jackson, resigned his seat and returned home, determined to overturn the sale. Making skillful use of county grand juries and newspapers, Jackson and his allies gained control of the legislature. After holding hearings that substantiated the corruption charges, Jackson dictated the terms of the 1796 Rescinding Act, which was signed by Governor Jared Irwin and nullified the Yazoo sale. He also arranged for the destruction of records connected with the sale; ensured that state officials tainted by Yazoo were denied reelection and replaced by his own anti-Yazoo, pro-Jefferson supporters; and in 1798 orchestrated a revision of the state constitution that included the substance of the Rescinding Act.

Courtesy of Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries.

To prevent those claiming lands under the Yazoo purchase from receiving a sympathetic hearing in a Congress dominated by Federalists, Jackson and his lieutenants blocked any cession of the western territory until the Republicans were in control. Then, in the Compact of 1802, commissioners from Georgia, including Jackson, transferred the land and the Yazoo claims to the federal government. The United States paid Georgia $1.25 million and agreed to extinguish as quickly as possible the remaining claims of Native Americans to areas within the state.

Northern speculators who had acquired land from the Yazoo companies pressed Congress for payment, but for more than a decade congressmen sympathetic to Georgia rebuffed them. Frustrated claimants sued for redress. In the case of Fletcher v. Peck

Courtesy of Georgia Info, Digital Library of Georgia.

Georgia politicians used the “Yazoo” label to bludgeon opponents for almost twenty years following the congressional settlement. A more tragic legacy of the Yazoo fraud grew out of the 1802 cession to Congress. As cotton culture spread across Georgia, the national government proved unable to extinguish Creek and Cherokee claims to land quickly enough for white Georgians, who were rapidly laying claim to inland tracts through the land lottery system. Anger over this matter fueled the development of the states’ rights philosophy, for which Georgia’s leaders became notorious in the 1820s and 1830s as they continually prodded the United States to complete the process of Indian removal. In a sense, the Yazoo land fraud helped lead to the Cherokee “Trail of Tears” in 1838.