Largely forgotten today, Nap Rucker was one of the premier left-handed baseball pitchers in the major leagues during the first two decades of the twentieth century, and may have invented, along with a teammate, the knuckleball.

George Napoleon Rucker was born to Sarah Hembree and John Rucker, a Confederate veteran, on September 30, 1884, in Crabapple, a small town in Fulton County near Roswell and Alpharetta. After dropping out of school, Rucker worked as an apprentice printer. One day he set in type the headline, “$10,000 For Pitching A Baseball.” Upon seeing the headline, Rucker decided to become a professional pitcher. He began his minor league career late in 1904 with the Atlanta Crackers of the Southern Association and spent the next two seasons with the Augusta Tourists of the South Atlantic League, compiling a record of forty wins and twenty losses while rooming with Ty Cobb.

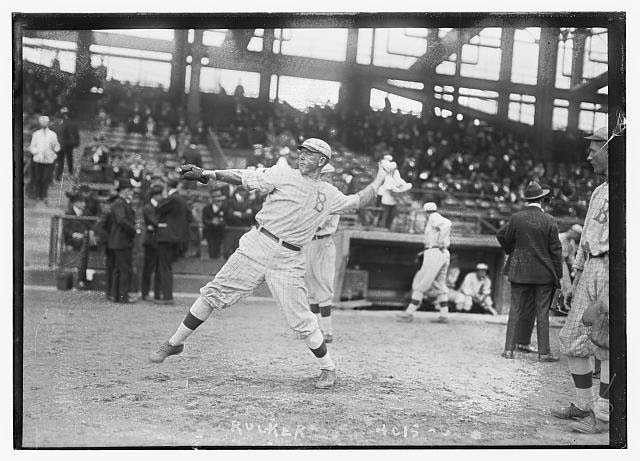

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

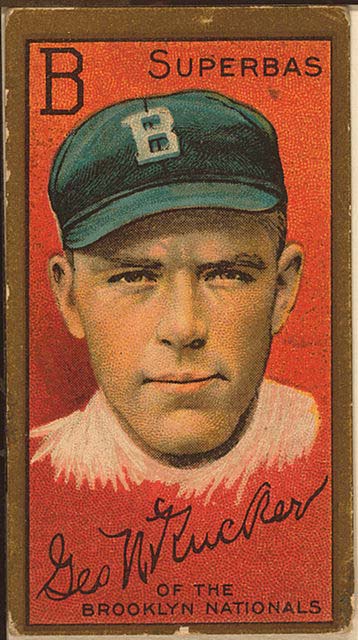

Rucker spent his entire ten-year major league career playing for the hapless Brooklyn Superbas of the National League. (The name Superbas, adopted in 1899, came from a popular vaudeville troupe of the time. The team later became the Brooklyn Dodgers.)

Rucker debuted in Brooklyn in 1907 and immediately became the team’s best pitcher, leading the Superbas in games, innings, strikeouts, and earned-run average. His fifteen wins were second best on the team. In 1908 he emerged as a National League star, winning seventeen games for a club that managed only fifty-three victories. Rucker finished third in the league in innings pitched and second in strikeouts. He also pitched a no-hitter, striking out fourteen Boston Doves while walking none. Teammate errors denied Rucker what would have been only the fourth perfect game in baseball history. In 1910 he led the National League in complete games, innings pitched, and shutouts. He had his finest season in 1911, winning twenty-two games, more than a third of his team’s sixty-four victories, and coming within one out of pitching another no-hitter. He was fourth in the league in innings pitched and third in strikeouts.

Rucker lost the speed on his overpowering fastball in 1913, and he hurt his arm the following season. For the last four years of his career, he relied on an assortment of off-speed pitches, especially the knuckleball. He was one of the first players in baseball history to throw this pitch, and evidence suggests that Rucker, in collaboration with fellow pitcher and Augusta teammate Eddie Cicotte, may have invented the knuckleball in 1905.

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Rucker compiled a lifetime .500 record of 134 victories and 134 losses while performing for teams that posted a cumulative .442 winning percentage during the time he pitched. His thirty-eight shutouts accounted for 28 percent of his wins, the second highest percentage in baseball history. Every year from 1908 to 1912 he was among the National League leaders in numerous pitching categories, including appearances, complete games, innings pitched, strikeouts, shutouts, and earned-run average. Baseball Magazine selected Rucker for its National League all-star team four times and to its best-in-baseball squad three times. The legendary Major League Baseball Hall of Fame manager John McGraw deemed Rucker the best left-handed pitcher of his era, and venerable sportswriter Ring Lardner chose Rucker for his all-time all-star team. In 1967 Rucker became the third professional baseball player (after Luke Appling and Ty Cobb) to be inducted into the Georgia Sports Hall of Fame.

Rucker retired as a player after the 1916 season and scouted for Brooklyn from 1919 to 1934 and again in 1939 and 1940. He discovered many players who went on to successful major league careers. He also helped to launch the baseball career of Earl Mann, who, as president and owner of the Atlanta Crackers, was one of minor league baseball’s most respected and successful executives.

Rucker was also a prominent businessman and politician in Roswell. He owned a plantation, several cotton farms, and a wheat mill, and he invested in the local bank. Rucker was elected unopposed as Roswell’s mayor during the Great Depression, and he brought the town its first supply of running water. After serving as mayor he was the city’s water commissioner for many years.

Rucker died at the age of eighty-six on December 19, 1970. He is buried in the cemetery of Roswell Presbyterian Church.