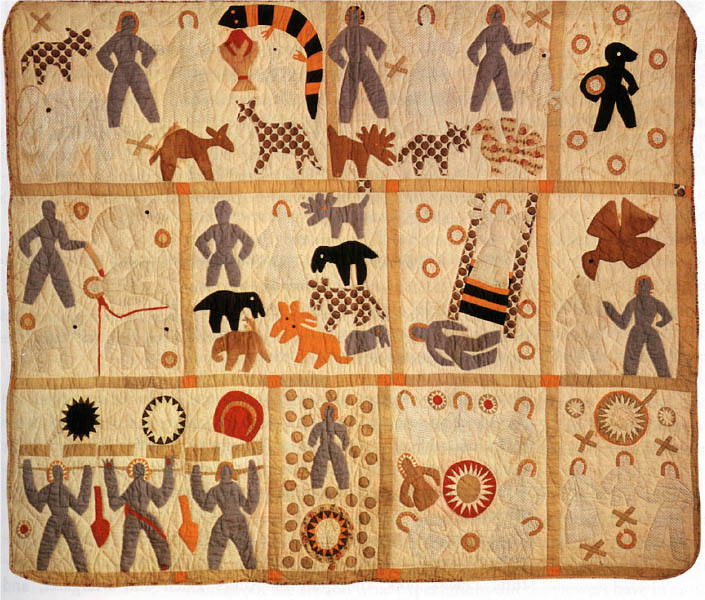

Harriet Powers is one of the best-known southern African American quilt makers, even though only two of her quilts, both of which she made after the Civil War (1861-65), survive today. One is part of the National Museum of American History collection at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. The second quilt is in the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, Massachusetts. The cotton quilts consist of numerous pictorial squares depicting biblical scenes and celestial phenomena. They were constructed through applique and piecework and were hand and machine stitched.

Powers was born into slavery near Athens on October 29, 1837, and lived more than half her life in Clarke County, mainly in Sandy Creek and Buck Branch. The first of the Powers quilts was displayed in 1886 at a cotton fair in Athens, where Jennie Smith, an artist and art teacher at the Lucy Cobb Institute, a school for elite white females in Athens, saw it. She asked to purchase it from Powers, but Powers declined to sell it. Smith remained in touch with Powers, however, and five years later Powers, having financial difficulties, agreed to sell the quilt for five dollars. At the time of the sale Powers explained the imagery in the squares, and Smith recorded the descriptions along with additional comments of her own.

Courtesy of National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution

The history of the second quilt is less clear. One account indicates that the wives of Atlanta University (later Clark Atlanta University) faculty members saw the first quilt in the Cotton States Exhibition in Atlanta in 1895 and decided to commission a second quilt by Powers. Another account suggests that the second quilt was purchased by the same faculty wives who may have seen it at the Nashville, Tennessee, Exposition in 1898. Regardless, the faculty wives presented the quilt to the Reverend Charles Cuthbert Hall of New York in 1898, while he was serving as the chairman of the board of trustees at Atlanta University. Subsequently, the folk art collector Maxim Karolik acquired it from Hall’s heirs and donated it to the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.

Powers’s quilts are remarkable for their bold use of applique for storytelling and for their extensive documentation. Her use of technique and design demonstrates African and African American influences. The use of appliqued designs to tell stories is closely related to artistic practices in the republic of Benin, West Africa. The uneven squares suggest the syncopation found in African American music.

Only one image of Powers herself survives. The photograph, made about 1897, depicts her wearing a special apron with appliqued images of a moon, cross, and sun or shooting star. Such celestial bodies appear repeatedly in her quilts and are often carefully stitched in complex ways, indicating their importance to her. These images may have related to a fraternal organization or had religious significance to her. Powers’s interpretations of both quilts have survived, though they are likely influenced by their recorders. Powers herself probably was illiterate and may have used the quilts as visual teaching tools for telling biblical stories.

In January 2005 Cat Holmes, a doctoral student in history at the University of Georgia, discovered the grave of Harriet Powers, as well as that of Powers’s husband and daughter. The headstone, which was uncovered at the historic Gospel Pilgrim Cemetery in Athens, reveals that Powers died on January 1, 1910.

She was inducted into Georgia Women of Achievement in 2009.