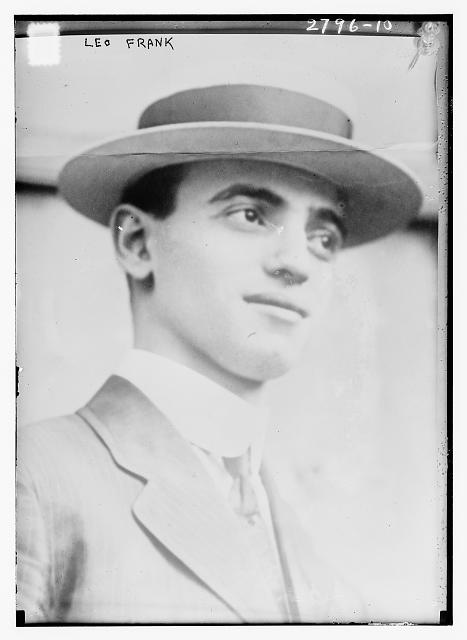

The Leo Frank case is one of the most notorious and highly publicized cases in the legal annals of Georgia. A Jewish man in Atlanta was placed on trial and convicted of raping and murdering a thirteen-year-old girl who worked for the National Pencil Company, which he managed. Before the lynching of Frank two years later, the case became known throughout the nation. The degree of anti-Semitism involved in Frank’s conviction and subsequent lynching was enough of a factor to have inspired Jews, and others, throughout the country to protest the conviction of an innocent man.

The Murder

On April 26, 1913, Mary Phagan, the child of tenant farmers who had moved to Atlanta for financial gain, went to the pencil factory to collect her week’s wages. Leo Frank, the superintendent of the factory, paid her. He was the last person to acknowledge having seen Phagan alive. In the middle of the night, the factory watchman found her bruised and bloodied body in the cellar and called the police. The city was aghast when it heard the news. Rumors spread that she had been sexually assaulted before her death. The public demanded quick action and swift justice.

Courtesy of Atlanta History Center.

The Evidence

Because eyewitness accounts placed both Frank and Phagan at the factory prior to her death, police arrived at Frank’s home early on April 27 for questioning. Frank denied knowing Phagan by name, but police reported that he seemed nervous. Detectives then took Frank to the morgue to view Phagan’s body and to the scene of the crime, where they observed his behavior, before concluding, for the time being, that he was not likely the murderer.

Frank was not arrested until April 29, the evening of Phagan’s funeral, when public outrage regarding her murder reached a fever-pitch. Under pressure to solve the case, detectives re-examined information they had been given earlier. A young worker said she did not see Frank when she came in shortly after Phagan to receive her pay, despite Frank saying he had stayed at the factory for at least twenty minutes after Phagan left. The night watchman said Frank called the factory later in the day on April 26 to see if everything was alright, which he had never done before. On the basis of this evidence, Leo Frank was arrested.

Prior to Frank’s arrest, four men were arrested in conjunction with Phagan’s murder between April 27 and 28, 1913: Arthur Mullinax, a streetcar conductor who was seen with Phagan the night before she died; Newt Lee, the Black night watchman who discovered Phagan’s body; John Gantt, a former bookkeeper at the factory; and Gordon Bailey, an elevator operator at the factory. On May 1 Jim Conley, a Black janitor at the pencil factory, was arrested after he was found rinsing what appeared to be bloodstains out of a shirt. However, Conley was not charged and was the state’s main witness against Frank, providing at least four contradictory affidavits explaining how Frank forced him to help dispose of Phagan’s body.

The Trial

Photograph from Wikimedia

Based mainly on the testimony of the janitor, who had been held in seclusion for six weeks before the trial on orders from Solicitor General Hugh M. Dorsey, the jury convicted the defendant. Frank’s attorneys were unable to break Conley’s testimony on the stand. They also allowed evidence to be introduced suggesting that Frank had many dalliances with girls, and perhaps boys, in his employ.

Atlantans hoped for a conviction. They surrounded the courthouse, cheered the prosecutor as he entered and exited the building each day, and celebrated wildly when the jurors, after twenty-five days of trial, found Frank guilty.

The Appeals

Within weeks of the trial’s outcome in early September, friends of Frank sought assistance from northern Jews, including constitutional lawyer Louis Marshall of the American Jewish Committee. Marshall gave advice about what information to include in the appeal, but Frank’s Georgia attorneys ignored his counsel. Frank’s lawyers filed three successive appeals to the Supreme Court of Georgia and two more to the U.S. Supreme Court, all on such procedural issues as Frank’s absence when the verdict was rendered and the excessive amount of public influence placed on the jury. Ultimately the U.S. Supreme Court, still on procedural grounds, denied Frank’s appeals; however, a minority of two, Oliver Wendell Holmes and Charles Evans Hughes, dissented. They noted that the trial was conducted in an atmosphere of public hostility: “Mob law does not become due process of law by securing the assent of a terrorized jury.”

The Governor’s Decision

Courtesy of Georgia Historical Society.

When all the court appeals had been exhausted, Frank’s attorneys sought a commutation from Georgia governor John M. Slaton. Thomas E. Watson, a former Populist and the publisher of the Jeffersonian, had conducted a campaign denouncing Frank that struck a chord, and Georgians responded to it. Watson’s accusations against Jews and Leo Frank, in particular, increased the paper’s sales and elicited enormous numbers of letters praising him and his publication. As Watson continued to fan the flames of public outrage, his readership grew. By the time Slaton reviewed the case, there was tremendous pressure from the public to let the courts’ verdicts stand.

Slaton reviewed more than 10,000 pages of documents, visited the pencil factory where the murder had taken place, and finally decided that Frank was innocent. He commuted the sentence, however, to life imprisonment, assuming that Frank’s innocence would eventually be fully established and he would be set free.

Slaton’s decision enraged much of the Georgia populace, leading to riots throughout Atlanta, as well as a march to the governor’s mansion by some of his more virulent opponents. The governor declared martial law and called out the National Guard. When Slaton’s term as governor ended a few days later, police escorted him to the railroad station, where he and his wife boarded a train and left the state, not to return for a decade.

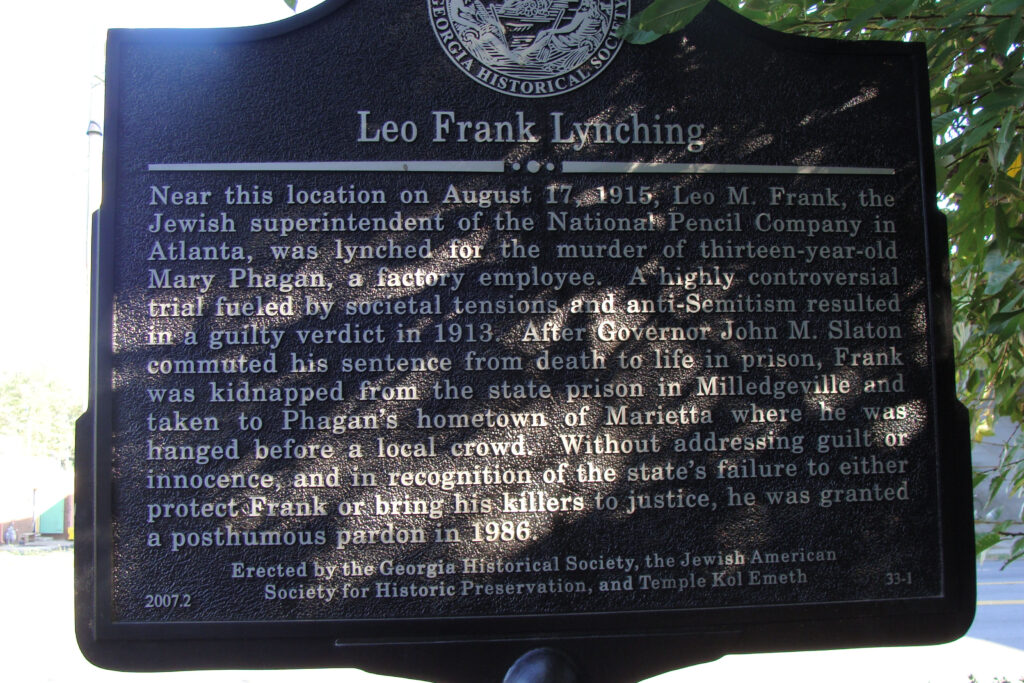

The Lynching

After Slaton’s commutation, Frank was interned at a prison farm in Milledgeville for just under two months. During his internment, a fellow prisoner slashed Frank’s throat with a knife, though he survived. Frank’s stay at the prison farm was cut short on the night of August 16, 1915, when twenty-five prominent citizens of Marietta, identifying themselves as the Knights of Mary Phagan, caravanned to Milledgeville, took Frank from his cell, and drove him back to Marietta, Phagan’s hometown, where they hanged him from an oak tree. Only months later, many of these same men would take part in the nighttime ceremony at Stone Mountain that established the modern Ku Klux Klan.

A crowd of nearly three thousand people gathered the next morning in Marietta to view Frank’s hanging body. The crowd grew increasingly unruly, and undertakers had to wrestle Frank’s body away before it could be further battered.

Conclusion

The Frank case not only was a miscarriage of justice but also symbolized many of the South’s fears at that time. Workers resented being exploited by northern factory owners who had come south to reorganize a declining agrarian economy. Frank’s Jewish identity compounded southern resentment toward him, as latent anti-Semitic sentiments, inflamed by Tom Watson, became more pronounced. Editorials and commentaries in newspapers all over the United States supporting a new trial for Frank and/or claiming his innocence reinforced the beliefs of many outraged Georgians, who saw in them the attempt of Jews to use their money and influence to undermine justice.

Frank’s trial had far-reaching impacts. It struck fear in Jewish southerners, causing them to monitor their behavior in the region closely for the next fifty years—until the civil rights movement led to more significant changes. But it also inspired the formation of the Anti-Defamation League, one of the nation’s foremost civil rights organizations.

In 1986 the Georgia State Board of Pardons and Paroles pardoned Frank, stating:

Without attempting to address the question of guilt or innocence, and in recognition of the State’s failure to protect the person of Leo M. Frank and thereby preserve his opportunity for continued legal appeal of his conviction, and in recognition of the State’s failure to bring his killers to justice, and as an effort to heal old wounds, the State Board of Pardons and Paroles, in compliance with its Constitutional and statutory authority, hereby grants to Leo M. Frank a Pardon.

The pardon was motivated in part by the 1982 testimony of eighty-three-year-old Alonzo Mann, who as an office boy had seen Jim Conley carrying Mary Phagan’s body to the basement on the day of her death. Conley had threatened to kill Mann if he said anything, and the boy’s mother advised him to keep silent. For those who thought Frank innocent, this provided confirmation; for those who believed him guilty, this was insufficient evidence to change their views.

The case inspired several scholarly treatments by historians and also made its way, through various media, into the popular culture. In 1915 Georgia musician Fiddlin’ John Carson wrote a ballad about Mary Phagan, which he performed on the steps of the state capitol to protest the commutation of Frank’s sentence. Ten years later the song was recorded as “Little Mary Phagan” by Moonshine Kate, Carson’s daughter, and around the same time Carson recorded a related song, “The Grave of Little Mary Phagan.”

Other popular interpretations of the case include the film They Won’t Forget (1937), based on Ward Greene’s fictionalized account Death in the Deep South (1936), with Lana Turner playing the victim in her first credited screen role; the television mini-series The Murder of Mary Phagan (1988), starring Jack Lemmon as Governor John Slaton; two novels—Richard Kluger’s Members of the Tribe (1977), a detailed reconstruction of the case, but set in Savannah rather than Atlanta, and David Mamet’s The Old Religion (1997), in which a fictionalized Frank tells his story in the first person; and Atlanta playwright Alfred Uhry’s Broadway musical Parade (1999), the title a reference to both the Confederate Memorial Day parade that brought Mary Phagan to town and the lynch mob that took Frank from Milledgeville to Marietta.

In 2008 the William Breman Jewish Heritage Museum in Atlanta opened a special exhibition entitled Seeking Justice: The Leo Frank Case Revisited, and in 2009 an episode of the PBS series American Experience entitled “The People v. Leo Frank” premiered in Atlanta, where the program was also filmed.