Georgia’s agricultural industry plays a significant role in the state’s economy, contributing billions of dollars annually. Agricultural labor, while no longer the largest source of work for Georgians today, has nevertheless shaped the culture and identity of the state.

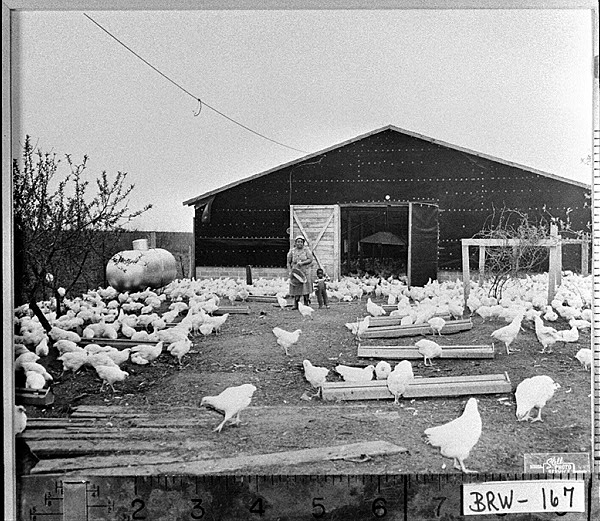

Once viewed primarily as a cotton state, Georgia now consistently ranks first in the nation’s production of poultry and eggs and is also a top producer of peanuts, pecans, tobacco, blueberries, and peaches. Overall, the state accounts for 2 percent of total U.S. agricultural sales.

The food and fiber sector is very diversified and includes the production and processing of a wide range of commodities. Georgia has 9.9 million acres of land devoted to farms, with an average farm size of 235 acres. In 2019 Georgia had more than 42,000 individual farms, and the state’s farmers sold more than $9.5 billion worth of agricultural products.

Georgia’s top products include the poultry and egg industry, which accounted for a third of Georgia’s farm commodities, with three out of four counties involved in poultry and egg production. In addition to producing the most broilers (chickens intended for consumption), Georgia produces the majority of the nation’s peanuts and is one of the highest producing states for cotton, pecans, and watermelons.

Other crops produced in Georgia include apples, berries, cabbage, corn, cottonseed, cucumbers, grapes, hay, oats, onions, peaches, rye, sorghum grain, soybeans, tobacco, tomatoes, vegetables, and wheat, as well as ornamentals, turf grass, and other nursery and greenhouse commodities. Beef cattle, dairy cows, and hogs are produced on farms throughout the state. Miscellaneous livestock such as meat goats and sheep, catfish, trout (aquaculture), and honeybees are also produced.

Georgia’s agricultural statistics are reported annually by county and commodity in the Georgia Farm Gate Value Report, compiled by Georgia’s Cooperative Extension Service county agents.

Early History

When General James E. Oglethorpe led the first settlement of English colonists at Savannah in 1733, one of their goals was to find crops that could be profitably grown and exported to England. Oglethorpe sought the advice and counsel of Tomochichi, leader of the Yamacraw people, who were skilled in hunting, fishing, and cultivating maize (corn), beans, pumpkins, melons, and fruits of several kinds. With the colonists learning successful food cultivation from the Yamacraw, the Trustees of the colony also established an experimental garden of ten acres in Savannah to find profitable agricultural exports. Employing botanist Hugh Anderson to collect seeds, drugs, and dyestuff from other countries with similar latitudes, the Trustee Garden served as an early agricultural experiment station to research what could be grown in Georgia.

These early experiments yielded mixed results. Attempts to produce wine and olives largely failed, and the orange trees that bordered the crosswalks of the garden suffered from springtime frosts. Mulberry trees, to feed silkworms, fared better, and Georgia’s small silk industry produced enough for Queen Caroline of England to wear a dress made of Georgia silk for her fifty-second birthday in 1735. While silk production increased to nearly a ton by 1767, it required huge subsidies by the British government and was frequently unprofitable.

More lucrative was rice cultivation, which was first pioneered in the neighboring South Carolina Lowcountry. Yet rice required a lot of land and labor, both of which were in short supply given Trustee policies that prohibited slavery and required small landholdings. After tremendous pressure, the Trustees ended the ban on slavery in 1750, and royal authorities eased limits on land ownership when taking over Georgia the following year. The colony’s agriculture soon gravitated toward a plantation system resembling neighboring South Carolina, producing cash crops like rice, indigo, and sometimes cotton. While small farms dominated Georgia on the eve of the American Revolution (1775–83), much of the colony’s most profitable crops were produced by enslaved African laborers on expanding plantations.

“King Cotton”

Cotton and tobacco became the major crops in Georgia after American independence because the loss of British markets and subsidies undercut other lucrative crops like indigo. Initially, cotton was limited to Georgia’s sea islands, but the invention of the cotton gin by Eli Whitney in 1793 near Savannah revolutionized the cotton industry. Short-staple cotton that could grow across Georgia but was limited by the difficulty of removing its green seeds now became profitable through the ginning process. Combined with the accelerating British industrial revolution, the cotton gin enabled the expansion of cotton across the state. By 1860 there were 68,000 farms in the state, and they produced 700,000 bales of cotton. Only 3,500 farms had 500 acres or more, and 31,000 had fewer than 100 acres of land.

Enslaved Black laborers and indigenous peoples bore the costs of rapidly expanding cotton production. When soil in cotton growing areas of east central Georgia declined in nutrients, enslaving plantation owners sought after more fertile lands in southwestern Georgia and in states further west. The Creek and Cherokee peoples were then forced from their lands by dubious treaties, while Black families were broken up as enslavers moved their workforce westward.

The Civil War (1861-65) dramatically changed the state’s agricultural labor force by freeing thousands of enslaved laborers, but cotton continued to be the main crop in many parts of Georgia. In 1870 more than 725,000 bales of cotton were produced, largely by Black sharecroppers who were often compelled to farm the lands of former enslavers.

Intensive cotton production continued to deplete Georgia’s soil. Agricultural leaders as early as the mid-1800s extolled the virtues of diversifying the state’s agriculture and recommended that greater emphasis be placed on livestock, poultry, orchards, vineyards, vegetables, forage, and forestry. Still, because cotton was such an attractive cash crop to lenders, it dominated agriculture not only in Georgia but throughout the South for many decades. A long depression in cotton prices for the remainder of the nineteenth century trapped Black sharecroppers and an increasing number of their white counterparts in debt peonage, foreclosing the possibility of social mobility.

In 1915, however, the boll weevil spread into southwest Georgia, destroying thousands of acres of cotton. That pest, combined with a very low price for cotton after World War I (1917-18), made diversification imperative. Moreover, outdated and damaging farming practices, such as plowing furrows without respect to the land’s contour and intertilling (planting short crops beneath tall crops, which increases productivity but depletes the soil) resulted in topsoil erosion by the 1920s.

Cotton production dropped from a high of more than 5 million acres and 2,769,000 bales in 1911 to only about 500,000 bales by 1923. More recently in 2018, 1,305,000 acres of cotton were harvested, with a total of 1,955,000 bales produced and cash receipts of $735,696,000. Cotton is no longer “king” in Georgia, but remains important as its sales still accounted for more than 23 percent of the total cash receipts for crop production in 2017.

Farm Population

Georgia remained an agrarian state until after World War II (1941-45). The rural population did not decrease much between 1920, when there were 2.1 million rural people and 310,000 farms, and 1960, when there were still 1.98 million rural residents. Over time, though, the proportion of the population living in rural areas decreased from about 85 percent in 1900 to 37 percent by 1990.

Multiple factors contributed to the decrease in Georgia’s rural population. First, the Great Depression and U.S. president Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal programs disrupted the sharecropping system, which was a large part of Georgia’s agricultural economy at the turn of the twentieth century. The Agricultural Adjustment Act, for example, paid landowners not to plant certain crops, which decreased landowners’ need for sharecroppers and enabled them to evict impoverished Black and white laborers. When conditions improved, landlords purchased labor-saving machinery instead of rehiring sharecroppers.

The rural population also decreased as factories and urban centers expanded at a rapid pace during World War II, and as war veterans attended college on the GI Bill. These graduates either explored nonagricultural careers or embraced modern, industrialized agriculture with large mechanized farms. The need for agricultural labor increased again near the end of the twentieth century when landowners turned increasingly to food crops that could not be harvested by machinery. Increasingly, migrant workers from Latin America filled the need of maintaining and harvesting crops.

As of 2017 only about 42,000 farms remained in Georgia, and less than 10 percent of Georgia’s citizens worked in agriculture or forestry. Slightly more than 9.9 million acres are classified as farmland, with an average farm size of 235 acres. Nearly half of all Georgia farms made less than $2,500 in 2017, while 15 percent made more than $100,000.

Although the number of farms in Georgia continues to decrease—from about 47,000 in 2007 to 42,000 in 2017—farms are growing in size. Average farm acreage in the state increased by 3 percent between 2012 and 2017.

The economic impact of the food, fiber, and related industries was estimated in 2019 at more than $73 billion. That includes $13 billion in farm gate value, or the value of the product when it leaves the farm, and about $60 billion in processing value. Agriculture supports more than 392,400 jobs in the state, and Georgia consistently ranks as the top forestry state in the nation.

Although the service sector employment has surpassed agricultural employment since the end of the twentieth century, farm production continues to be a central part of Georgia’s economy.