The impact of the Anglican Church, or Church of England, in Georgia reaches beyond religion, for it was largely due to the political influence of the church’s key members that the English established the colony of Georgia in 1733. Before the American Revolution (1775-83) Anglicans constituted the largest and most influential group of Christians in Georgia.

Image from Roman Eugeniusz

Anglicanism originated in the sixteenth century, when King Henry VIII left the Roman Catholic Church to establish a new state church. At the time Georgia was founded, anyone holding a political position in England was required to be Anglican.

James Edward Oglethorpe, the founder of the Georgia colony, was a member of the British Parliament in the 1720s, before he ventured to America. With the new colony, Oglethorpe sought a more humanitarian way for England to deal with its “worthy poor,” who at the time were often incarcerated for indebtedness. Other members of Parliament hoped to convert Native Americans in the region to Christianity, while the British government saw a need for a political and military buffer to protect its colonies in Virginia and the Carolinas against possible encroachment by the Spanish, who had colonized Florida. Sending settlers to Georgia promised a way to meet all three of these needs. Missionary priests (Anglican ministers) would provide moral leadership to the colonists and preach to Native Americans, while the settlements established by these newcomers would act as a barrier against Spanish incursion.

Courtesy of Oglethorpe University

Among those working with Oglethorpe was the influential Anglican priest Thomas Bray, founder of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel to Foreign Parts. Bray had for thirty years worked with other church members to send missionaries to English colonies. He had also visited several of the colonies in America and had gathered a group of solid supporters at home, called Associates of Dr. Bray. One major thrust of their activities was the solicitation of donations to pay missionaries’ salaries. Another was the provision of books for the missionaries. Bray’s group sent books by the caseload, intending for them to be used by the ministers and to form “a publick library” in the new colony. Early Georgia records show that religious books in the “Indian language” and in German (for working among Moravian settlers) were sent as well.

The charter establishing Georgia as a colony was formalized in 1732, with a Board of Trustees appointed to guide the new enterprise. One-fourth of the twenty-one Trustees were clergy. Although there was some discussion of the establishment of the Church of England as the official church of Georgia, groups of various religious persuasions were permitted to worship in the new colony. (Catholicism was banned in Georgia, however, until 1777.) The Trustees did appoint Anglican clergymen to serve the new colonists, however, and saw to it that 300 acres were provided for the support of an Anglican church in Savannah, including a parsonage and cemetery.

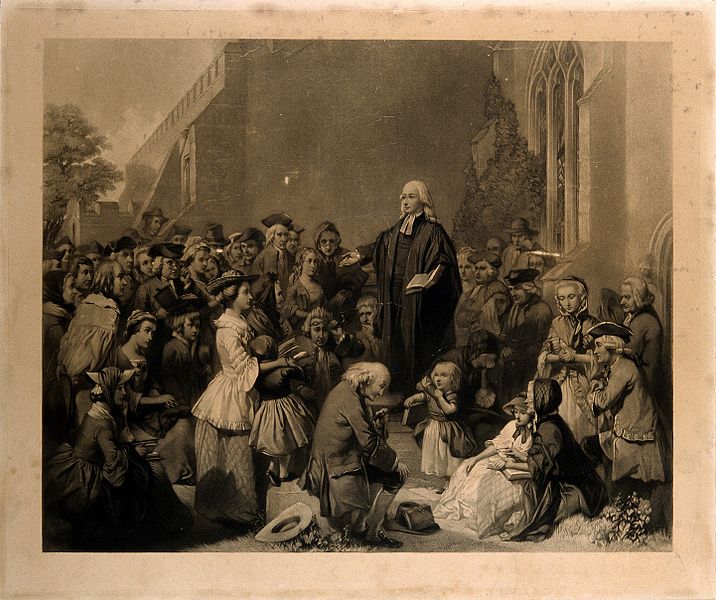

Photograph from Wellcome Trust, Wikimedia

The first priest selected by the Trustees was a volunteer, Henry Herbert, who sailed with the original colonists, reaching Georgia in 1733. Herbert founded Christ Church of Savannah, the first Anglican parish, or self-supporting congregation, in Georgia; but he died during his return voyage to England before the year ended. The Trustees appointed a series of nine Anglican priests in the first twelve years of the colony. Although the Trustees interviewed and appointed the priests, the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel paid the priests’ salaries.

The Trustees also established charity schools to ensure that children understood the Anglican catechism. Teachers were supervised by Anglican clergymen, but children of all faiths were invited to attend. (Indians; Sephardic, or Spanish-speaking, Jews; Huguenots; and Moravians were among those living in the environs.) One of the prime results of these charity schools was the ready acceptance of English as the official language of Georgia.

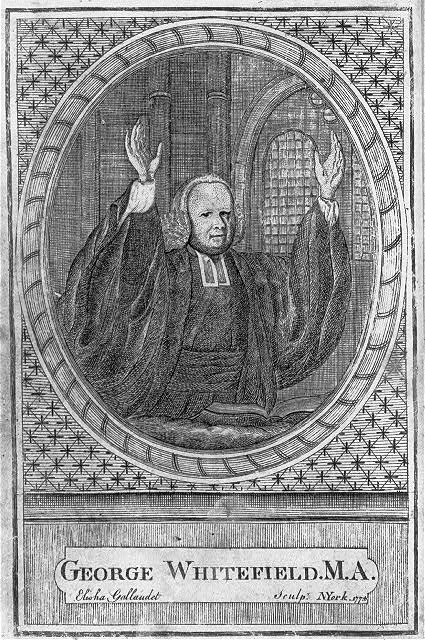

Perhaps the best-known Anglican priest in Georgia’s history is John Wesley, appointed by the Trustees to serve as rector, or the priest in charge of a parish, of Savannah’s Christ Church in 1735. Wesley apparently considered himself successful in his mission to convert the Indians, and he ministered to the local Huguenots and Moravians in their own languages. He alienated some of the prominent colonists, however, with his rigid interpretation of church rules and teaching. After only two years he returned to England, where not long afterward he developed Methodism. Twenty-three-year-old George Whitefield, another early Anglican missionary priest in Georgia, gained fame for his eloquent sermons and departure from staid liturgical Church of England rites. Although he was rector of Christ Church, Whitefield devoted so much energy to founding and supporting the orphanage called Bethesda, near Savannah, that the Trustees soon found another priest for Savannah’s Anglicans.

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

John Wesley’s brother, Charles Wesley, served as resident minister of Frederica for a brief time in the 1730s, and by 1751 Augusta and Savannah each had an Anglican clergyman in residence. Traveling missionaries served other colonial Georgia communities, including those at Abercorn and Ebenezer, until the American Revolution. By the 1770s more than half of Savannah’s residents were members of the Church of England, and a good number of others were spread throughout the colony. Unwilling to leave the faith when the colonies revolted, Anglicans in America formally reconstituted themselves in 1789 as the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America. Other than political affiliations, the tenets of the faith were not changed, and Anglicans in America are generally known as Episcopalians.