The Catholic Church in Georgia is both one of the earliest and one of the fastest-growing religious institutions in the state. As of 2012, approximately 1.2 million Catholics reside in Georgia and are served by either the Archdiocese of Atlanta or the Diocese of Savannah.

The Early Church

The Catholic Church established itself in Georgia long before James Oglethorpe founded the colony in 1733. Spanish priests came to Georgia in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries seeking to convert Native Americans. The Spanish missions had limited success. Although the Jesuit and Franciscan orders managed to win over some locals, Catholicism failed to persevere once the British arrived.

Oglethorpe led the British effort to establish a colony in Georgia. He hoped to create an enlightened society in Britain’s southernmost American colony, while the British wanted Georgia to serve as a buffer zone between (Protestant) British Carolina to the north and (Catholic) Spanish Florida to the south. Oglethorpe encouraged such diverse, often oppressed, groups as the Lutheran Salzburgers, who established the Ebenezer settlement, and Spanish and German Jews to settle in the new colony. In recognition of its role as a military buffer and a haven for religious outcasts, however, the colony forbade the practice of Catholicism. When Georgia converted to a royal colony in the 1750s, the ban on Catholicism remained.

Catholics would not find acceptance in Georgia until the American Revolution (1775-83). The values of the Revolution and its emphasis on individual liberty, including the freedom of religion, overcame some of the prejudice against Catholics. Furthermore, a group of nearly 3,900 French, Haitian, and Irish Catholic troops fought for the new nation at the Siege of Savannah in 1779. The people of Georgia did not forget these brave soldiers, among them the Polish count Casimir Pulaski, for whom Fort Pulaski is named. The state constitution of 1777 rewarded Catholics with some rights, although it prevented them from holding political office. Catholicism remained dormant in Georgia until the formal acceptance of the U.S. Constitution in 1789, when Catholics received equal rights under Georgia law.

Antebellum Era

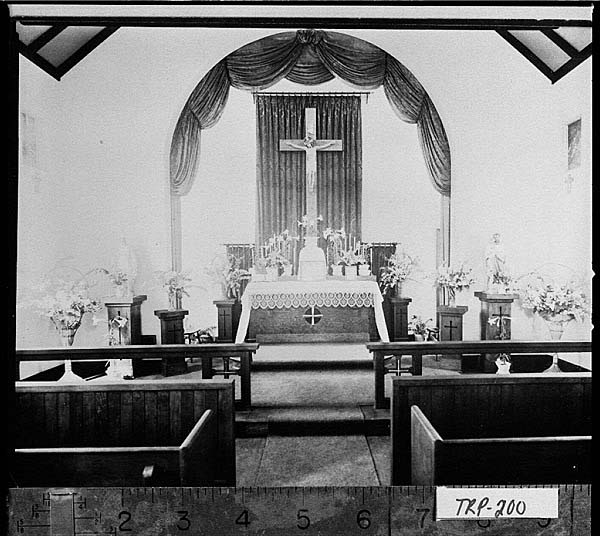

In the early 1790s, taking advantage of the new freedom in Georgia and seeking to escape economic hardship in Maryland, a group of English settlers established Georgia’s first permanent Catholic congregation in an area called Locust Grove, near modern-day Sharon. Well into the nineteenth century this resilient community welcomed subsequent groups of Irish Catholic immigrants, including the family of Margaret Mitchell’s mother, the Fitzgeralds.

French Catholics, fleeing the French Revolution, settled in Savannah in the mid-1790s. Other small Catholic communities formed in Augusta and along the coast. The biggest challenge they all faced was maintaining their faith, as no priest had yet been assigned to Georgia by the Vatican. The Savannah community eventually brought a couple of French priests to the state, but the lack of clergy and the distance between congregations meant that Catholicism did not so much grow as merely survive in the early republic.

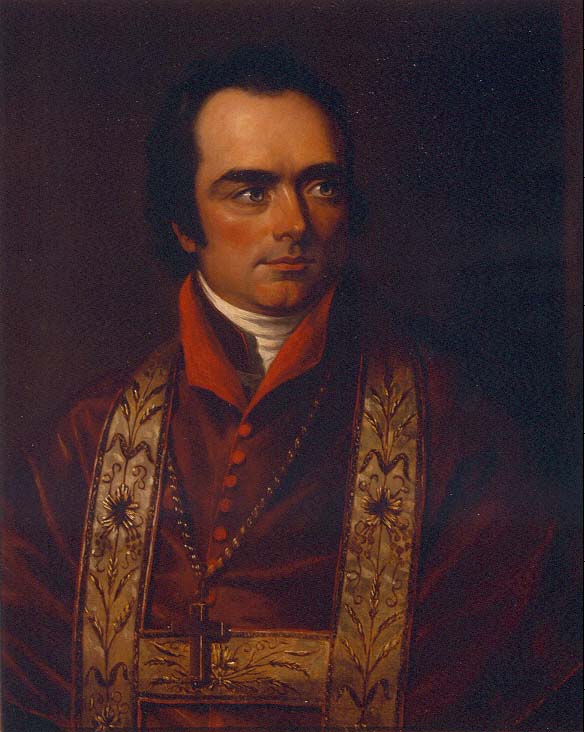

This problem plagued the church throughout the South. To remedy the situation, the Vatican created a diocese in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1820. The Diocese of Charleston covered both North and South Carolina, as well as Georgia. The church hoped that introducing episcopal authority into the region might stabilize Catholicism and encourage its growth. The man chosen to lead this new diocese was John England, a thirty-four-year-old Irishman.

Bishop England served the new diocese for more than twenty years. During his administration (1820-42) he laid the groundwork for many important Catholic institutions in the state. Catholic communities spread across Georgia to include Columbus and the former Cherokee lands. England recruited a generation of priests and nuns who served both Catholics and the state faithfully. He also created an order of nuns, the Sisters of Mercy, who came to Georgia in the 1840s and established St. Vincent’s Academy in Savannah. Dedicated to the causes of education and health care, the sisters settled across Georgia, where they continue to teach in schools and operate hospitals in Athens, Atlanta, and Savannah.

Where England made his greatest gains, however, was with the Protestants of the South. Having grown up in Ireland, with its established (Protestant) Church of Ireland, the young bishop appreciated the religious freedom of his new home. He enthusiastically praised America, befriended Protestants, and championed the South. Although he did not endorse slavery, he rebuked those who condemned it from the outside, and in so doing won the trust of many southern leaders. He instilled in his clergy the need to support the South spiritually and morally. This lesson would serve Catholics well in Georgia; generally, Catholics in Georgia faced less prejudice than did northern Catholics during the 1850s.

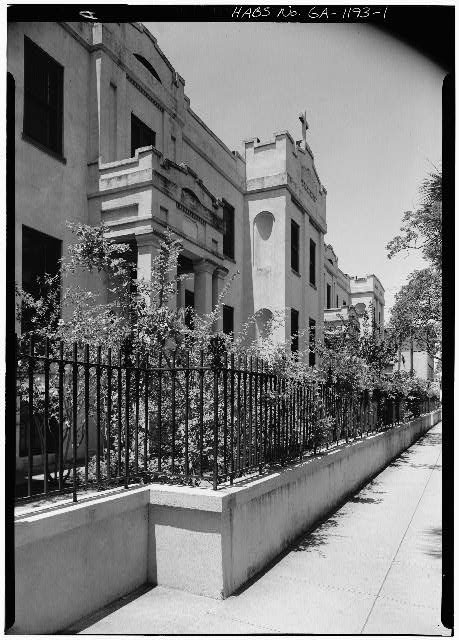

By 1850 Catholics had grown to more than 5,000 strong in Georgia. The Vatican responded by creating the Diocese of Savannah in 1850. Savannah, because of its port and economic ties along the Atlantic seaboard, remained the center of Catholicity in the state until the early twentieth century. The city took in a great number of Irish and German Catholics in the mid-nineteenth century. The church also had a noticeable presence in middle Georgia, in Macon, Augusta, and Columbus. In 1848 the church that would later become known as the Shrine of the Immaculate Conception opened in Atlanta. Smaller communities often grew up elsewhere in the state around the railroad camps, where many of the laborers were Irish Catholics.

Civil War and Reconstruction Era

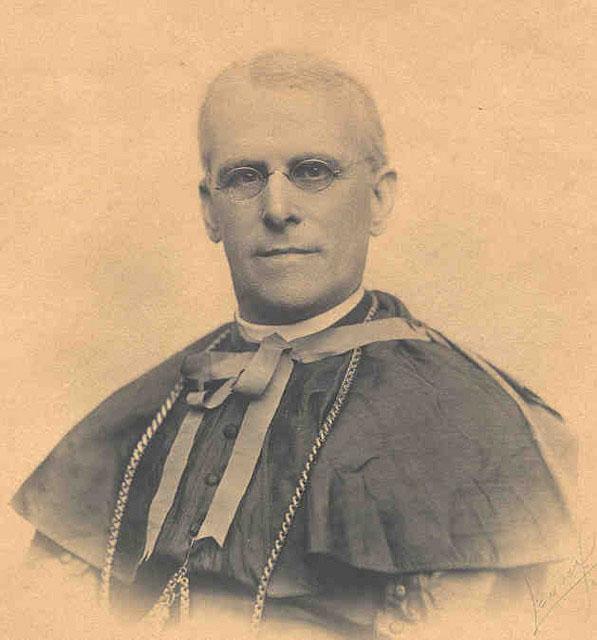

In 1861, on the eve of the Civil War, the diocese welcomed its third bishop, the French-born Augustin Verot. He came to Savannah from St. Augustine, Florida, where he had served for many years. He guided the diocese through the difficult years of the Civil War (1861-65) and Reconstruction (1867-76). Verot was a fairly popular leader and an ardent supporter of the Confederacy. While still in Florida in January 1861, he defended slavery in a sermon that caused a national sensation and earned him the title “Rebel Bishop.” While he supported the South, Verot also sought to care for the African Americans in the diocese.

Catholic loyalty to the Confederacy helped to cement the religion’s place in Georgia during and after the war. The Sisters of Mercy played an important role as nurses in Confederate hospitals. Priests often were the only ministers at the prisoner-of-war camp at Andersonville. Catholic men served in Confederate units throughout the war, side by side with Protestants. In November 1864 Atlanta priest Thomas O’Reilly convinced General William T. Sherman to spare not only O’Reilly’s Immaculate Conception Church but also St. Philip’s Episcopal Church, Central Presbyterian, Trinity Methodist, and Second Ponce de Leon Baptist (then Second Baptist) from burning. Father Abram Ryan, the “poet-priest of the Confederacy,” edited the pro-South newspaper Banner of the South in Augusta after the war. While there he wrote many of his well-known poems, such as “The Conquered Banner.” Catholics’ staunch support of the South before and after the war was rewarded with a deeper degree of acceptance by their fellow Georgians.

Signs of this acceptance came from a number of places. As communities struggled to create and maintain public schools, a number of cooperative educational programs appeared across the state. Starting in Savannah in 1870, and continuing in Macon and Augusta, Catholic primary schools joined the local public school systems. These arrangements remained in place until the early twentieth century. In the Vineville section of Macon in 1874, the diocese, with the support of the city, opened Pio Nono College, which included a seminary. This venture failed to attract many students, and the diocese ultimately turned the school over to the Jesuits, who renamed it St. Stanislaus. In Savannah in 1876, the church celebrated the opening of the spectacular Cathedral of St. John the Baptist, built over three years. When the cathedral burned in 1898, the church and its contents were valued at $175,000 to $200,000, and many non-Catholics in the state aided in the fundraising to rebuild the church. By the dawn of the twentieth century, the Catholic Church enjoyed high esteem in Georgia.

The Rise of Anti-Catholicism

The growth of Catholicism the late nineteenth century, however, combined with other factors to place Catholics in a difficult position. While the Catholic Church had a decidedly Irish face in Georgia, others, such as Lebanese, Italian, Hungarian, and African American groups, also contributed to the church’s growth. Church leaders recruited foreign priests to address the growing needs of the diocese. French Marists served in Atlanta and Brunswick, Jesuits ministered to Macon and Augusta, and German Benedictines came to Savannah. Protestants greeted this influx of foreign Catholics with alarm.

At the same time, Catholics were gaining political strength in the urban areas of the state. Irish communities in Georgia created a powerful faction in the Democratic Party, and Catholic political influence soared. Perhaps Georgia’s best-known Catholic politician was Patrick Walsh of Augusta. Walsh edited the Augusta Chronicle and served in the Georgia legislature for a number of years. When the Populist Party, led by Thomas E. Watson, rose to challenge the Democrats of Augusta in the 1890s, Walsh helped to crush the grassroots movement, often through ballot-box stuffing and other disingenuous means. He was appointed to fill the remainder of Alfred H. Colquitt’s senatorial term in 1894. He then served as mayor of Augusta from 1897 until his death in 1899. Walsh epitomized the rising Catholic power in the state, but the means by which he maintained power made him, and his church, vulnerable to attack.

Georgia witnessed a marked rise in anti-Catholicism starting in the late nineteenth century. In response to the incessant corruption of Democratic politics in middle Georgia, a group called the American Protective Association challenged what it claimed were the dangers of Catholic influence. Predominantly found in the Midwest, the American Protective Association came to Georgia and successfully dismantled the Catholic public school systems in Macon and Augusta. They also showed Georgians an underlying resentment among the poor and disaffected that could be tapped.

Tom Watson did not openly attack the church until around 1908. Using his newspaper the Jeffersonian, Watson began attacking the church, particularly the priesthood. He found that readers responded strongly to his attacks on these “foreign foes,” attacks that consequently became more frequent and virulent. His stories grew quite outlandish and lewd, and Watson eventually found himself embroiled in an ongoing battle with the government for publishing obscene material. Although his attacks lacked credibility, they echoed a tone of intolerance that was growing in Georgia. In 1915 the state witnessed the rebirth of the Ku Klux Klan. This modern Klan committed itself to attacking African Americans, Jews, and Catholics. Around this time, pro-Watson factions in the state legislature passed the Convent Inspection Act, which allowed local grand juries to inspect local convents, orphanages, and other Catholic institutions to ensure that people were not being held against their will, which was one of Watson’s frequent claims.

Catholics slowly rose to challenge this bigotry. Watson’s attacks on the priesthood had been so successful that the Church had to use leading lay members to repel his allegations. Speaking as good citizens of Georgia who also happened to be Catholic, the Catholic Laymen’s Association distributed pamphlets that both refuted the lies spread by bigots about the church and corrected common misconceptions held by Protestants about Catholics. In a remarkable statewide effort beginning in 1916, the Catholic Laymen’s Association managed to blunt much of the anti-Catholicism that the American Protective Association, Watson, and the Klan had created over the previous two decades.

Distinguished Georgia Catholics

Despite periods of bigotry, Catholics often were able to mitigate hostility through their service to the faith and to the state. Bishops England and Verot fended off criticism from outsiders through their defense of the South. The Sisters of Mercy at St. Vincent’s in Savannah garnered enormous goodwill when they aided the family of Confederate president Jefferson Davis after the Civil War. Benjamin Keiley, bishop from 1900 to 1922, had many admirers who appreciated his former career as a soldier in Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. Flannery O’Connor earned tremendous fame as a writer who infused her fiction with a strong sense of Catholicism.

Many Georgians distinguished themselves within the church as well. In the mid-1880s James Augustine Healy of Clinton, born of an Irish father and a mulatto mother, became the first priest of African American heritage in the country and later served as bishop of Portland, Maine. His brother Patrick also joined the priesthood and served as president of Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., for almost a decade. A century later, Eugene Marino was ordained archbishop of Atlanta in 1988, becoming the first Black archbishop in America.

Named as Atlanta’s first archbishop in 1962, Paul J. Hallinan not only advocated racial equality in the South, but also played a significant role at the Second Vatican Council in Italy. Monsignor Joseph L. Bernadin served as Hallinan’s auxiliary bishop in Atlanta before going on to serve as archbishop of Cincinnati, Ohio, and he later rose to the position of cardinal in Chicago, Illinois.

The Modern Church

The explosive growth of the Atlanta region spurred more change within the church. In the early twentieth century, Savannah still claimed about a third of the state’s some 18,000 Catholics, but recognizing the importance of Atlanta, the diocese reorganized into the Diocese of Savannah-Atlanta in 1937. The Cathedral of St. John the Baptist in Savannah served as co-cathedral with the newly constructed Christ the King in Atlanta, a Gothic-style structure situated on four acres of land along Peachtree Street in Atlanta’s Buckhead community. In 1956 the Vatican split the diocese, and the northern counties of Georgia, with about 23,000 Catholics, constituted the new Diocese of Atlanta. In 1962 the Vatican raised Atlanta to the position of archdiocese. Both dioceses grew significantly during the growth of the Sunbelt and with an influx of Hispanic and Asian immigrants. In the late 1990s the Archdiocese of Atlanta initiated a campaign to open a number of new schools to serve north Georgia. It now claims almost two dozen elementary schools and four high schools. The archdiocese comprises more than 1 million Catholics, while the Savannah diocese numbers approximately 78,000. What once had been a handful of scattered communities across the state now ranks as one of its largest sects.

In January 2005 Wilton Gregory was ordained as Atlanta’s third African American archbishop. (James P. Lyke, who served from 1991-92, was the second.) A native of Chicago, Gregory is notable for being named the youngest bishop in America, at age thirty-five, and for serving as the first African American president of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops. Gregory spoke in Spanish the opening words of his installation Mass in Atlanta, an acknowledgment of the burgeoning Hispanic Catholic population in the archdiocese.