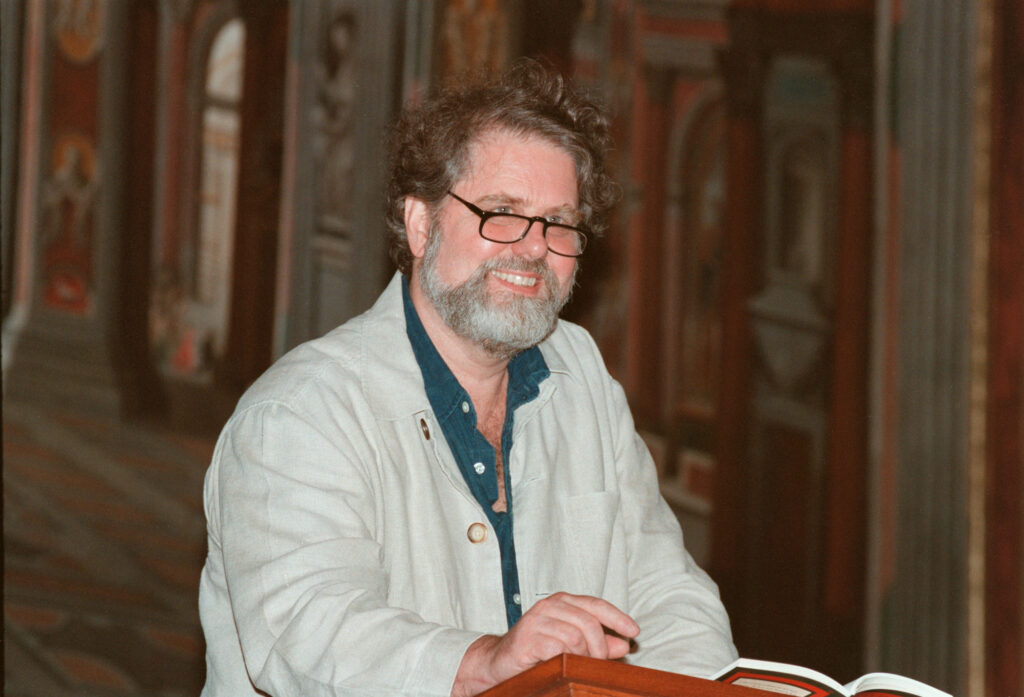

Coleman Barks, a poet and professor emeritus at the University of Georgia (UGA) in Athens, has gained great renown for his translations of Near Eastern poets, especially Jalal al-Din Rumi.

He is an accomplished poet, whose interest in Near Eastern mysticism infuses his observations of southern landscape and life. Barks has published several collections of his own poetry and numerous poetry translations, and his work has appeared in a wide array of anthologies, textbooks, and journals, including the Ann Arbor Review, Chattahoochee Review, Georgia Review, Kenyon Review, New England Review, Plainsong, Rolling Stone, and Southern Poetry Review. He was inducted into the Georgia Writers Hall of Fame in 2009.

Coleman Bryan Barks was born on April 23, 1937, in Chattanooga, Tennessee, to Elizabeth Bryan and Herbert Bernard Barks. His sister, Elizabeth, also became a writer, and her fiction has been published under the name Elizabeth Cox. Barks attended Baylor School, where his father served as headmaster for thirty-five years, and later received his Ph.D. in English from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. In 1962 he married Kittsu Greenwood. The couple had two children, Benjamin and Cole, before they divorced. After teaching for two years at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, Barks joined the faculty of the UGA English department. Since his retirement from UGA in 1997, Barks has lived in Athens, where he works on his poetry and translations and operates Maypop Books, which publishes translations of Rumi and other Near Eastern religious poets, as well as Coleman’s own work.

Poetry

Barks’s first poetry collection, The Juice (1972), reflects the range of styles and subjects he developed more fully later in his career. Considerable whimsy, a common feature in Barks’s poetry, occurs alongside a tendency toward the meditative, an appreciation of the natural world, and an interest in people and relationships. The poems in the book’s first section, “Body Poems,” describe parts of the human body in sensual, imagistic, sometimes enigmatic ways. In the poem “Spine,” for example, the backbone, “a curl of rainwater / down the windshield / moves around / like it’s hearing / the radio.” The second section, “Choosing,” contains longer narrative poems. Many seem autobiographical, describing people or experiences from Barks’s life. Poems in the third section, “The Swim,” tend to be shorter; many of them are about animals. In form some of these poems, consisting of couplets or three-line stanzas, at first seem more conventional than the free-flowing narrative style Barks would later favor. But even at this relatively early point in his career, Barks has mostly abandoned rhyme and conventional meter for a more relaxed, improvisational, even musical approach to language. An example is “The Coyote Cage at the Athens (Ga.) Zoo,” which is composed of four three-line stanzas using irregular three-foot lines. The poem comments on the unnatural state of a coyote living in a small-town zoo and imagines its release from captivity: “Nobody could live / like you do, you dumb // beast. Come out of there / and lie down in the grass / with me. Easy. Good boy.”

Barks’s work continued to appear in journals and anthologies, and in the mid-1970s he published two chapbooks of poetry, New Words (1976) and We’re Laughing at the Damage (1977). In 1993 Barks published his second major collection of poetry, Gourd Seed. The poems in this volume reflect the work of a poet with wide-ranging interests. His preferred style in Gourd Seed is narrative, with an emphasis on description and meditation. He writes about his family, experiences in the natural world, old friends, the Persian Gulf War (1990-91), and other subjects. Some poems verge on the comic and nonsensical: in “Summer Food” he delights in recounting the names of vegetables (“O, to put the whole pod / of Okra in the mouth”), while in “W R F C” he recounts the forty-nine entries he submitted to a contest inviting listeners to name the call letters of a radio station (“WITHOUT REASON FISH CHANGE / WE RADIATE FLIRTATIOUS CHARM / WOPSIDED RED FOLDING CHAIRS”)—these entries he compares to the random connections he has made with people in his life. Other short poems describe objects and moments of curiosity or wonder—flowers, animals, encounters with strangers, an attempt to repair a door, or memories. One humorous poem describes an encounter with a strange child in a grocery store parking lot.

Barks is especially effective in longer narrative poems, which he typically begins by focusing on a specific subject or theme that he then extends into wider speculations. The influence of Rumi and other mystic poets Barks has translated is evident in the longer poems. An example is “A Section of the Oconee near Watkinsville,” which begins with a description of his difficulties navigating a canoe down a shallow stream and ends with ruminations on trying to lead a balanced life, of trying to follow a teacher whose “example is everywhere open, / like a boat never tied up, no one in it, / that drifts day and night, metallic dragonfly / above the sunken log.” In “Hymenoptera” an encounter with angry yellow jackets becomes a subtle meditation on life’s randomness and the poet’s power or powerlessness to influence his own future. One of the finest poems in Gourd Seed is “New Year’s Day Nap,” in which the sight of his son sleeping on a sofa leads Barks to ponder his role as a parent and the lives of his sons, now grown. Interspersed through this poem are excerpts from a hymn, printed in shape-note form. When Barks reads the poem out loud (an experience the printed version cannot convey), he sings the hymn.

Club, a collection of poems written with and about his granddaughter, followed Gourd Seed in 2001. The light and playful verse in this volume allows full expression of the humor and whimsy typical of many poems written throughout Barks’s career. Poems about children, especially about what children do and say, occur frequently not only in Club but also in Tentmaking (2002), Barks’s third major collection. These poems build on the styles and themes of Gourd Seed. Most are written in three-line stanzas. Still contemplative and inclined toward narratives, these later poems are tinged with concerns about mortality and about his fellow writers—Robert Bly, Emily Dickinson, Allen Ginsberg, Donald Hall, Seamus Heaney, William Matthews, Mary Oliver, James Wright, and others—as if Barks is assessing his own place among poets. Love, sex, dreams, his parents, animals, and strange encounters are also frequent subjects. Especially noteworthy are the title poem, “Tentmaking”; “Black Rubber Ball”; and “Elegy for John Seawright,” written in honor of a deceased friend. There are other equally compelling poems. “Hyssop” considers the pertinence of Jesus’ remonstrance to the Pharisees and suggests that only those without sin should cast the first stone at the sex scandal involving U.S. president Bill Clinton. “1971 and 1942” wistfully remembers his parents and their continuing effect on him: “What does it mean to me, The heart grows old.” “The Final Final” recounts with humor and sadness the day of his retirement, when Barks sleeps through the last final examination he would give and misses the chance to thank and say good-bye to his students:

I’m unrepentantly, sufficiently, some would say terrible, alone. Look / At me and be frightened of not pouring the last of the love and / wakefulness you’re given, which is every moment, but moreso some / than others. Emptying out is the point. In time, over time, be early.

Tentmaking contains some of the best poetry Barks has written. His more recent work reflects his continuing proficiency with narrative. The poem “Just This Once,” a letter to U.S. president George W. Bush arguing for alternatives to the Iraq War (2003-11), was widely distributed on the Internet prior to the start of the conflict.

In 2008 the University of Georgia Press published Barks’s Winter Sky: New and Selected Poems, 1968-2008.

Rumi Translations

Barks is internationally known for his translations of Islamic poetry. In 1976 the poet Robert Bly showed him some academic translations of Jalal al-Din Rumi, a thirteenth-century Islamic poet. Following Bly’s suggestion that “these poems need to be released from their cages,” Barks began translating the thousands of poems by Rumi. He has published numerous volumes of Rumi translations, including The Essential Rumi (1995), in collaboration with other translators. He has been interviewed by Bill Moyers as part of two Public Broadcasting Service television series on poetry, The Language of Life and Fooling with Words, and his translations of Rumi appear in the Norton Anthology of World Masterpieces. The Essential Rumi has even appeared on nonfiction best-seller lists around the United States.

In rendering 700-year-old poems for today’s readers, Barks claims “to make what I am given—which is literal, scholarly transcriptions of poems—into what I hope are valid poems in American English.” Persian poetry is highly structured, and Barks feels that reproducing the same sound patterns found in its rhyming syllables would produce a trivial effect in English. Instead, he has attempted “to connect these poems with a strong American line of free-verse spiritual poetry,” such as that of Theodore Roethke, Gary Snyder, Walt Whitman, and James Wright.

Rumi’s poetry can be seen as having influenced Barks’s own work. Rumi’s work often puts religious concerns into concrete images, for this mystic poet often uses fables, compares earthly love to sacred love, and puts the daily concerns of living in the context of spiritual challenges. “Don’t let your throat tighten / with fear,” Barks translates in the Essential Rumi. “Take sips of breath / all day and night, before death / closes your mouth.” The same concerns of essential love and daily life often can be seen in Barks’s own poetry, as in “New Year’s Day Nap”:

Some songs don’t ever get completely sung.

They’re sung by the blood,

inside creeks and rocks and air,

in some cellular Beulah land,

the harmonizing water sings them.

“Poetry became one of my ways,” Barks writes in “These Things, Hereafter.” The “way” that Barks indicates in all of his work—whether in the translations of centuries-old poems or in his own work—is that of a journey that will never be finished. Instead, it is one embarked upon because of the joys found in the journey itself.