Some of the most important figures in the history of commercial country music received their first significant exposure as performers at the annual Georgia Old-Time Fiddlers’ Conventions, which were held from 1913 to 1935. Among them were Fiddlin’ John Carson, Gid Tanner, Riley Puckett, and Clayton McMichen, all of whom went on to become nationally known radio and recording artists.

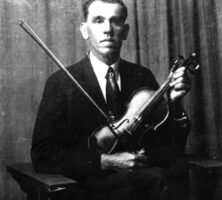

Courtesy of Phil Tanner

In April 1913, after a long weekend of music making in Atlanta, Georgia’s leading practitioners of traditional fiddling organized the Georgia Old-Time Fiddlers’ Association. For the next twenty-two years fiddlers from throughout Georgia met annually in Atlanta for several days of fiddling that ended in a contest in which the state’s fiddling champion for the ensuing year was selected.

These events received copious coverage from Atlanta’s three daily newspapers and attracted the attention of out-of-state journalists, who reported on them in nationally circulated newspapers and magazines. When a youthful Lowe Stokes defeated the elder statesman of Georgia fiddlers, Fiddlin’ John Carson, at the 1924 convention, the story was printed in the Literary Digest. In 1925 Stephen Vincent Benét published a poem titled “The Mountain Whippoorwill; or, How Hill-Billy Jim Won the Great Fiddlers Prize.” The similarity between published reports of the Stokes/Carson contest and the events recounted in “The Mountain Whippoorwill” suggests the likely source for Benét’s poem.

Photograph by Wilbur Smith

Unwittingly, the rustic musicians who performed at the Georgia Old-Time Fiddlers’ Conventions helped set the stage for two epochal developments in commercial country music that would occur in the next decade—the use of old-time musicians as recording artists and as sources of live talent on radio broadcasts.

The annual fiddlers’ conventions were held in the old Atlanta Municipal Auditorium (the lobby and front offices of which later became Georgia State University’s Alumni Hall) at the corner of Courtland and Gilmer streets. A typical convention began on a Thursday and ended the following Saturday night. The Thursday and Friday night programs were exhibition, or warm-up, programs and featured string bands, comedians, dancers, singers, and other types of entertainers in addition to the fiddlers. The contest, held on Saturday night, was usually followed by a square dance in the auditorium’s Taft Hall (later Veterans’ Memorial Hall).

Courtesy of Earl Gray

Audiences for the fiddlers’ conventions included former rural dwellers who had recently migrated to Atlanta in search of employment in the city’s textile mills and other industries. Among others who attended these annual musical events were local residents with rural Georgia roots who had become leaders in Atlanta’s business and political arenas. On many occasions members of Atlanta’s younger and urban-reared citizens came in search of something different in the way of entertainment.

With the introduction and growth of other such sources of entertainment as radio, motion pictures, and phonograph records, the fiddlers’ conventions began to lose their audiences, and in 1935 they came to an end. During the conventions’ heyday, crowned state champions included J. B. Singley (1913), Fiddlin’ John Carson (1914, 1923, 1927), Shorty Harper (1915, 1916), John Silvey (1917), A. A. Gray (1918, 1921, 1922, 1929), F. B. Coupland (1919), R. M. Stanley (1920), Lowe Stokes (1924, 1925), Earl Johnson (1926), Gid Tanner (1928), Joe Collins (1930), and Anita Sorrells Wheeler (1931, 1934).