Jackson Lee Nesbitt, a noted printmaker and painter of the American Scene, dedicated his artistic career to the portrayal of ordinary people going about the business of their lives. A native of Oklahoma, Nesbitt created scenes from the Midwest during the 1930s and 1940s, but in the 1950s, when interest in his work diminished, he moved to Atlanta and established a second career in advertising. Thirty years later, Nesbitt sold his business and resumed his artistic career from Atlanta.

Early Life and Education

Nesbitt was born in McAlester, Oklahoma, on June 16, 1913, the only child of LuCena Grant and Howard Nesbitt. The family resided in Muskogee, Oklahoma, where his father owned a commercial printing business. Jack, as Nesbitt was known, helped out in the family business until 1931, when he enrolled at the University of Oklahoma in Norman.

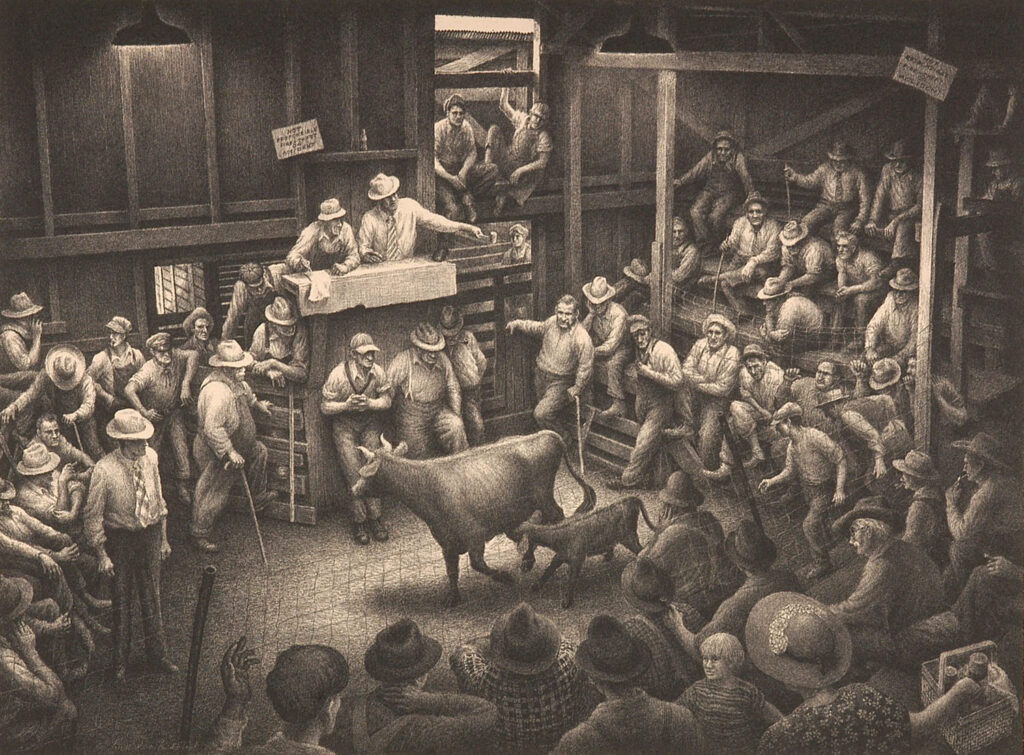

Courtesy of Morris Museum of Art

Two years later Nesbitt enrolled at the Kansas City Art Institute in Missouri. As a first-year student, he learned etching from John deMartelly, attended Ross Braught’s painting class, and met his future wife, Elaine Thompson, who was a costume design student. Thomas Hart Benton, who joined the faculty in the fall of 1935, quickly became a close friend and mentor to the younger artist.

In 1937 the management of the Sheffield Steel Corporation contacted deMartelly concerning an etching commission. Because Nesbitt was an outstanding student, his teacher suggested him for the job. When Nesbitt arrived at the plant one afternoon, he was taken to the open-hearth furnace area, where he diligently sketched anonymous workers in that dramatic setting until five o’clock the following morning. On the strength of his sketches, he was commissioned to create a series of etchings illustrating different phases of the steel industry. The commission launched Nesbitt’s career as a professional artist.

Artistic Career

The commission with Sheffield Steel Corporation provided the financial security that enabled Jack and Elaine Nesbitt to marry on June 1, 1938. He graduated from the Kansas City Art Institute about the same time. Working as a freelance artist, Nesbitt augmented his commissioned work with genre scenes of the Midwest, and he routinely went with Benton on sketching trips to rural Arkansas. The landscape and people of the Ozarks often appear in the finished work of both artists.

Courtesy of Morris Museum of Art

Beginning in 1939 Nesbitt’s work gained widespread recognition. Open Hearth Door, a Sheffield Steel Corporation painting, was chosen to represent Missouri in the American Art Today exhibition at the New York World’s Fair. Associated American Artists selected one of his etchings, Watering Place, for an edition of 250 prints that were sold through subscription. Having a print published by the association ensured national distribution, and four more of Nesbitt’s works, all of rural southern genre scenes, were later selected by the print publisher.

Over the next decade Nesbitt’s work was exhibited in California, Colorado, Illinois, Missouri, New York, and Oklahoma. He was awarded the Eames Prize by the Society of American Etchers in 1946, and his work was included in the book American Prize Prints of the Twentieth Century, by Albert Reese. Major corporations with operations in the Midwest, including Brown and Bigelow, Butler Manufacturing Company, Humble Oil and Refining Company, Omaha Steel Works, Pratt and Whitney Aircraft Corporation, and Standard Oil, commissioned Nesbitt to create illustrations for calendars, Christmas cards, and other publications.

From 1949 until 1951, as fewer commercial commissions came his way, Nesbitt taught etching at the Kansas City Art Institute. In 1955 he executed a print, Old Man with a Violin. It features Chris J. Gove, a local fiddle player, who often modeled at the Art Institute for Benton and deMartelly. Nesbitt pulled (printed) twenty-five prints but was unable to sell them. Over the twenty-year period from the date of his first professional etching, which was a self-portrait in the guise of a jester, to this 1955 print, Nesbitt celebrated ordinary life and American initiative, but with the rise of abstract expressionism, his work came to be perceived as quaint and old-fashioned.

Move to Atlanta

The artist sought a new livelihood in order to provide for his family, which by this time included three children—Kathryn, Evelyn Elaine, and Thomas. He sold his etching press and in 1957 relocated to Atlanta, where for a short period he was a painter and illustrator for the Lockheed Corporation before becoming an advertising salesman for Brown and Bigelow. He then established a company that sold advertising and, for nearly thirty years, stopped creating art.

Courtesy of Morris Museum of Art

In 1984 Nesbitt was visited by Norman and June Kraeft, owners of the June 1 Gallery in Connecticut, who admired his work. Their gallery was helping to lead the revival of interest in early-twentieth-century American prints. Though he explained that his career was long over, Nesbitt agreed to let the couple have his copper plate of Old Man with a Violin in order to make additional prints and complete the edition. All prints sold within a year, and Nesbitt was thrilled. His work had been “rediscovered.”

In 1987, eager to return to his artistic roots, Nesbitt sold his company, but he thought that etching would be difficult at his age and without his own press. Therefore he contacted Rolling Stone Press in Atlanta, a fine art lithography atelier that was close to his home. From 1988 until 1993, Nesbitt and Wayne Kline, a master printer and the owner of the press, collaborated on six lithographs. Kline had been trained as a master printer at Tamarind Institute in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Five of the prints are composite images based on sketches, people, and memories of Nesbitt’s life in the Midwest. Calhoun Street is different, however; although it is stylistically the same, this sixth print is not a memory but a fleeting moment captured by the artist from the window of Rolling Stone Press.

Nesbitt’s work is found in numerous museums and collections around the nation. His work may be found in Georgia at the Columbus Museum in Columbus and at the Morris Museum of Art in Augusta. Other institutions housing his prints and paintings include the Ackland Art Museum at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill; Boston Public Library in Boston, Massachusetts; Columbus Museum of Art in Columbus, Ohio; Library of Congress in Washington, D.C.; Memphis Brooks Museum of Art in Memphis, Tennessee; Muscarelle Museum of Art at the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia; and Orlando Museum of Art in Orlando, Florida.

Nesbitt died of heart failure in Tucker, near Atlanta, on February 20, 2008.