John Rollin Ridge (also known as Cheesquatalawny and Yellow Bird), considered the first Native American novelist, was born near New Echota (near the present city of Rome) on March 19, 1827.

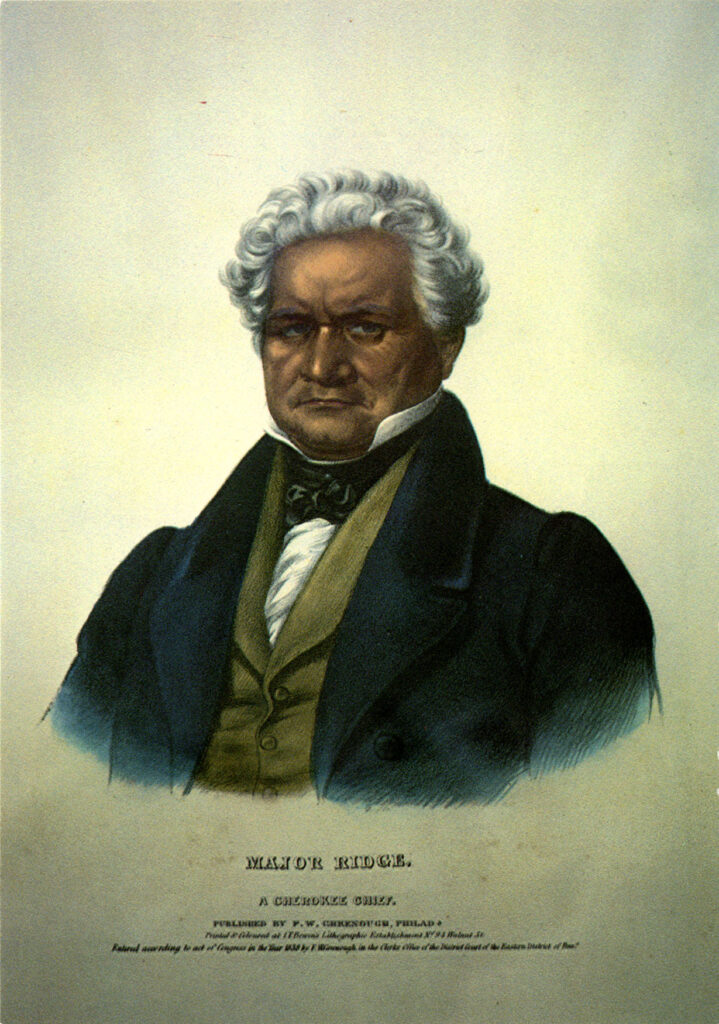

His grandfather Major Ridge, his father, John Ridge, and his uncles Elias Boudinot (Buck Watie) and Stand Watie led the Cherokee “Treaty Party,” which signed a removal agreement at New Echota in 1835. The four leaders were marked for execution by members of the John Ross party in 1839. All but Stand Watie were killed, and twelve-year-old John Rollin Ridge witnessed his father’s murder.

Publicly, the Ridge-Watie-Boudinot family embraced assimilation. Major Ridge adopted his first name from his rank in the Red Stick Creek War and sent his children to local missionary and New England boarding schools. In New England, Buck Watie adopted the name of his benefactor, Elias Boudinot. After John Ridge and Elias Boudinot married white brides in Cornwall, Connecticut, the two couples fled mobs and took refuge in the Cherokee Nation. After they returned to Georgia, the brothers established successful plantations. The family held enslaved people, yet educated the enslaved children; it was led by patriarchs, yet often driven by strongwomen.

By the time of John Rollin Ridge’s birth, Elias Boudinot could rightly claim that the Cherokee Nation had a far greater literacy rate and a more highly developed political structure than did the white population of Georgia. By 1828 Boudinot had begun publishing the bilingual Cherokee Phoenix, which he edited until 1832. John Rollin Ridge studied with Sophia Sawyer, a missionary teacher who strongly opposed the boarding school method of “civilizing” Native American students. During Ridge’s childhood, tension grew within the Cherokee Nation over the question of accommodation or resistance to white settlers’ encroachments on Cherokee territory. The 1828 Jackson election and Indian Removal Act of 1830 laid the groundwork for Georgia confiscation of Cherokee land and deepened the split between the Ross and Ridge parties.

After the 1835 Treaty of New Echota, the Ridge family settled comfortably in present-day Missouri. The mass removal of 1838 (the Trail of Tears) brought the Ross party into power, and the 1839 executions of Ridge’s father, uncle, and grandfather forecast further violence. John Rollin Ridge then moved to Fayetteville, Arkansas, with his widowed mother and in the 1840s read the law; married Elizabeth Wilson, a white woman; and wrote anti-Ross essays. In 1849 Ross sympathizer David Kell took and gelded a stallion that belonged to Ridge, who confronted and killed the man. Ridge then fled to Missouri and on to California in 1850 to join the gold rush. There his pen primarily served the Democratic Party, producing conventional poetry, acerbic essays, and what many consider the first Native American novel and the first novel written in California, The Life and Adventures of Joaquin Murieta, the Celebrated California Bandit (1854).

Set at a time when California was a cultural palimpsest reinscribed by a flood of would-be gold miners, Murieta tells the tale not of a displaced Cherokee but of a Sonoran, “born . . . of respectable parents.” He is “remarkable for a very mild and peaceable disposition” but encounters an outrage very much akin to what Ridge must have experienced at his father’s murder: “A band of these lawless men, having the brute power to do as they pleased, visited Joaquin’s house and peremptorily bade him leave his claim, as they would allow no Mexicans to work in that region. . . . Not content with this, they . . . ravished his mistress before his eyes.” In a curious inversion of the “Indian hater” motif, the peaceable youth remakes himself into a machine of revenge: “He had contracted a hatred to the whole American race, and was determined to shed their blood, whenever and wherever an opportunity occurred.”

Ridge’s preference for assimilation colors his narrator’s view of other Native Americans, contrasting the lowly Diggers and the “poor miserable, cowardly Tejons” to the effective “Cherokee half-breeds” who aid in the final hunt for Joaquin. Among the Americans, only those possessing “nobility” have any luck in pursuing the bandit, particularly “a chivalrous son of the South,” who “had grown up under a discipline which taught him that honor was a thing to be maintained at the sacrifice of blood or of life itself.” The book ends with “the important lesson that there is nothing so dangerous in its consequences as injustice to individuals—whether it arise from prejudice of color or from any other source; that a wrong done to one man is a wrong to society and to the world.”

Ridge, who contributed to a number of antiabolitionist papers before and during the Civil War (1861-65), spent the last seventeen years of his life working as a newspaper editor and writer for the Sacramento Bee and the San Francisco Herald, among other publications. Significant later poems include “Poem,””The Atlantic Cable,” and “California.” He died on October 5, 1867.