Larry Jerome Rubin published hundreds of poems in literary magazines and four volumes of selected verse after moving to Atlanta in 1950. He began a long academic career as an English professor at the Georgia Institute of Technology in 1956.

Though Rubin appeared in several collections of contemporary southern poets, his poems focused on historical images and the inner self rather than any particular time or place. Rubin was a self-described romantic poet whose inspirations included Emily Dickinson and whose writing included several articles on American romantic literature.

Rubin was born in 1930 in Bayonne, New Jersey, the son of Lillian Strongin and Abraham Joseph Rubin. Reared in Miami Beach, Florida, he studied briefly at New York’s Columbia University (1949-50) and earned degrees in journalism (B.A., 1951; M.A., 1952) and English (Ph.D., 1956) at Emory University in Atlanta. Immediately after receiving his doctorate, he became an instructor at Georgia Tech and eventually rose to full professor. Having received a Smith-Mundt Award from the U.S. State Department, Rubin taught American literature during the 1961-62 academic year at the Jagiellonian University of Kraków in Poland. He also spent three years overseas as a visiting Fulbright scholar—at the University of Bergen in Norway in 1966-67, at the Free University of West Berlin in 1969-70, and at the University of Innsbruck in 1971-72.

Rubin had already published numerous poems in literary magazines when “Instructions for Dying” won the Poetry Society of America’s Reynolds Lyric Award in 1961. His first volume of poetry, The World’s Old Way, appeared in 1962. Its introductory poem, “The Bachelor,” introduced Rubin’s signature persona, the bachelor-poet. In a Faustian vow to the solitary artist’s life, he traded the prospect of immortality through one’s children for a childless life spent conjuring magic from words. The World’s Old Way won the Georgia Writers Association’s Literary Achievement Award and Oglethorpe University’s Sidney Lanier Award (named for Georgia poet Sidney Lanier) for a first book of poems.

In 1965 the Poetry Society of New Hampshire presented its John Holmes Memorial Award to Rubin for the poem “For Parents, Out of Sight,” a line of which provided the title for his next collection. Lanced in Light (1967) explored the theme of time and its transformation of life and love. The Dixie Council of Authors and Journalists named him Georgia Poet of the Year in 1967 for Lanced in Light and again in 1975 for All My Mirrors Lie, his third book.

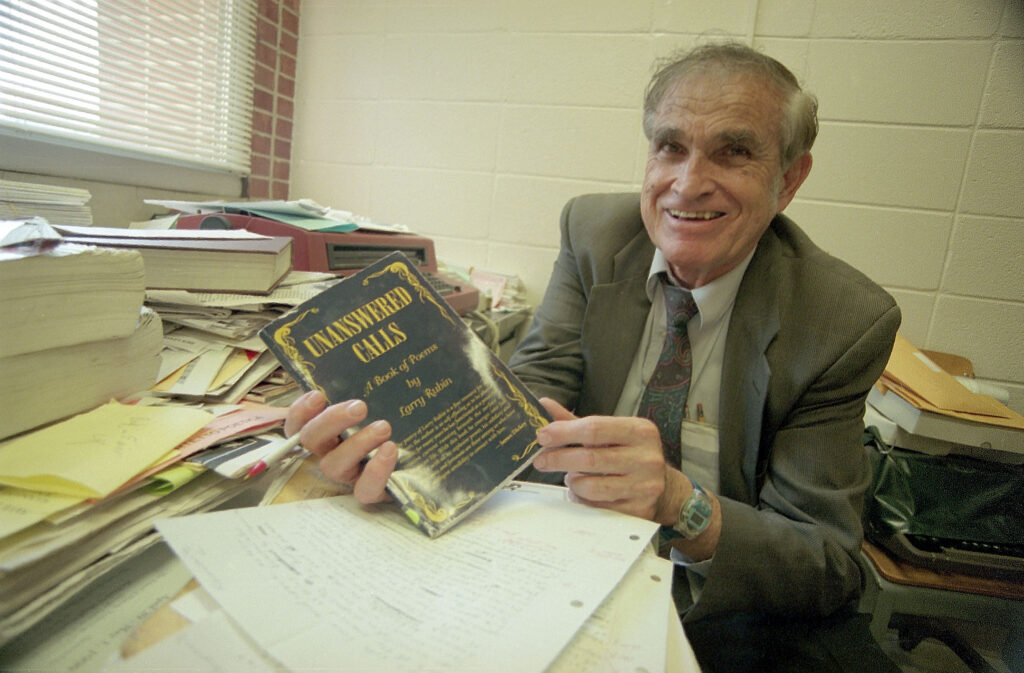

All My Mirrors Lie represented the bachelor-poet at middle age, his eye ranging the various “mirrors” of self reflected in his relationships with the living and the dead. The collection included “The Bachelor, as Professor,” for which Rubin received a lyric award from the Poetry Society of America in 1973. Unanswered Calls, Rubin’s fourth book, appeared in 1997. In it he expanded the territory he surveyed in the chapbook All My Mirrors Lie to include the vistas of an aging poet facing his accumulated memories and ghosts and looking forward to decay and death.

After retiring from Georgia Tech in 1999, Rubin continued to travel and write. A career member of the College English Association, a professional organization of teacher-scholars, he directed the association’s annual poetry workshop. In 2001, the CEA presented Rubin with its Life Membership Award. Emory University holds a collection of Rubin’s papers, which he donated before his death in 2018.