The Okefenokee Swamp and environs are a distinctive folk region, shaped by Celtic ethnicity, geographic isolation, and Primitive Baptist religion. The swamp alone covers more than 700 square miles of southeast Georgia and northwest Florida.

Indian peoples occupied the “land of the trembling earth” through the early 1800s, when most were driven out or forcibly removed by Europeans. From the early nineteenth through the mid-twentieth century, the swamp was home to an independent, self-sufficient community of “crackers,” most of whom came to Georgia from North Carolina and were of Scottish and Scots-Irish origin. They scratched out a living through livestock herding, subsistence agriculture, and naval stores.

For periods in its history, the Okefenokee Swamp was a refuge for Indian people, fugitives from slavery, deserters during the Civil War (1861-65), and others seeking concealment. Various traditional narratives deal with these topics, including accounts by present-day descendants of Indian people who fled to Fort Moniac on the St. Marys River during the Indian removals. In contrast to the widespread view that “there are no Indians in Georgia,” family folklore among these descendants suggests that some Indian people stayed in the Okefenokee area, hiding their heritage and intermarrying with early European American settlers.

During the 1800s this region had one of the smallest African American populations in the state. After the Civil War more Blacks were drawn to the interior of southeast Georgia by jobs in farming, turpentining, logging, and the railroad industry. Oral accounts describe the work songs of gandy dancers (crews of Black railroad track layers), sacred music of Black churches, and the blues and juke joints of the Black turpentine camps. Of these only the sacred music traditions continue in the region today.

Folkways and Storytelling Traditions

From 1912 to 1951 naturalist and folklore collector Francis Harper documented the traditions of European Americans living in and around the Okefenokee, including the region’s distinctive folk speech, tales, music, customs, home remedies, and beliefs. Harper’s work with the “Okefinokee folk” (the spelling harks back to early maps) was completed by his widow, Jean, and folklorist Delma Presley with the publication of Okefinokee Album (1981). The Harpers were instrumental in the establishment of the Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge in 1937, which ultimately resulted in the relocation of the swamp’s human inhabitants and ironically marked the end of the historic period of Okefenokee folklore that Harper had worked so hard to record.

Although people no longer live in the swamp, many Okefenokee folk traditions continue in nearby communities. Fishermen and hunters, for example, serve up “duck rice” and fried fish at camps and reminisce about the days of alligator hunting and frog gigging in what is now a federal wildlife refuge. A few individuals still make the traditional poled boats, suited to maneuvering in tight water.

Okefenokee families for years have taken advantage of the mild climate and large expanse of “honey plants” such as gallberry and tupelo gum to keep bees for honey. The counties surrounding the Okefenokee are now home to the state’s largest commercial honey operations. Beekeepers usually apprentice with other beekeepers, developing a keen knowledge of the woods, the habits of bees, and the rhythm of the seasons.

The distinctive ecosystem of the great swamp is the subject of legends, tall tales, and personal experience narratives about bears, 'gators, and other encounters with the natural world. Georgia’s best-known traditional storyteller was fishing guide Lem Griffis. Griffis, who died in 1968, entertained visitors to his fish camp outside Fargo with well-honed whoppers such as this tale, called “Odd Insects,” told to Kay L. Cothran: “See that honey a-sittin’ up there on the shelf? Well, I crossed my bees with lightnin’ bugs so they could see how t’ work at night, an’ they make a double crop o’ honey every year.” Stories about hunting and fishing, colorful characters of the past, and memories of growing up on one of the “islands” in the Okefenokee still abound in the region. In recent years, persons whose families had connections to Billy’s Island, for example, gather for an annual potluck and exchange memories at the Stephen Foster State Park outside Fargo.

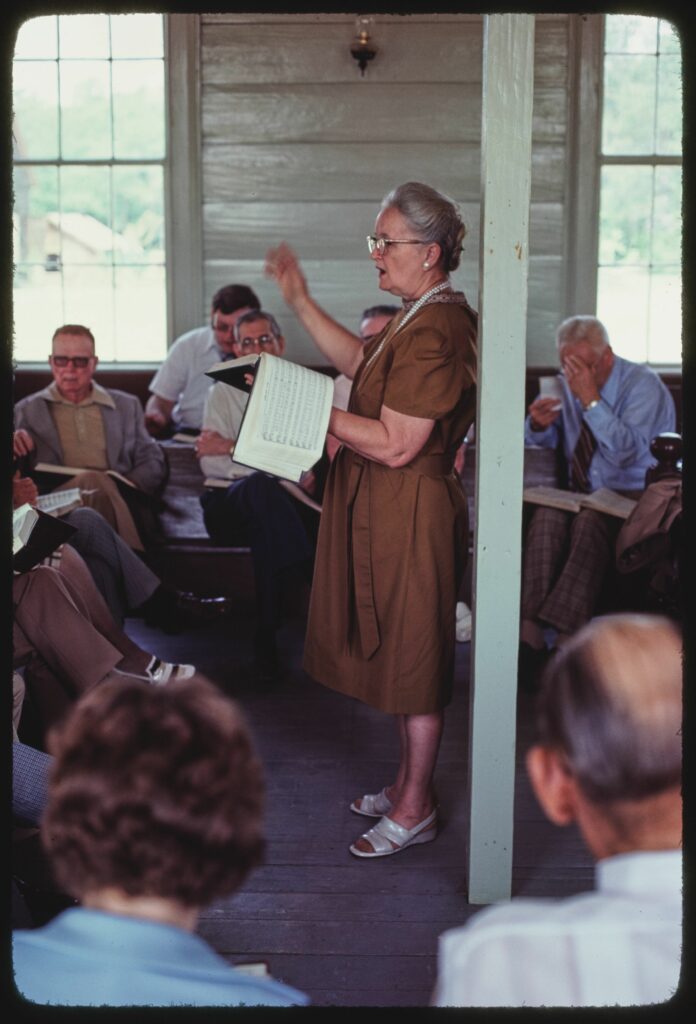

The Chesser Homestead on Chessers Island (outside Folkston) and other historic sites, such as Traders Hill (Folkston) and Obediahs Okefenok (Waycross), are focal points for family reunions and special community events. At the annual Chesser Open House, for example, Chesser family descendants and neighbors gather to talk, eat a simple meal cooked on the homestead’s wood-burning stove, and share with visitors customs associated with life on Chessers Island. Some demonstrations, such as making lye soap and washing clothes with a “battlin’ stick,” are nostalgic re-creations of past folkways. Others, such as quilting, palmetto broom making, turpentining, and Sacred Harp singing, are still practiced in the surrounding area.

Musical Traditions

Sacred Harp sings date back to at least the 1860s in the Okefenokee. The “shape-note” singing tradition in Georgia began during the antebellum period as a way to teach congregations to sing. Traveling teachers used “four-shape” tune books with religious lyrics in which different-shaped note heads were assigned to the European musical scale of fa, sol, la, and mi. Within southeast Georgia, conservative Primitive Baptist beliefs combined with the relative cultural isolation of the Okefenokee to foster a distinctive stylistic variant of Sacred Harp. Characteristics included walking time in a counterclockwise fashion according to the meter of the tune, and the same slow tempos and melodic ornamentation found in the Primitive Baptist meetinghouse. Primitive Baptist churches, with their unaccompanied, lined hymn traditions, exist in much smaller numbers today, but they have been a major force influencing local culture. The simple wooden meetinghouses of the Crawfordite subsect of Primitive Baptists are a distinctive feature of Okefenokee traditional architecture. Missionary Baptist, Pentecostal, and Methodist churches now dominate the region, however, and tent meetings, revivals, and gospel sings have superseded the Sacred Harp tradition.

Collector Francis Harper documented swamper secular music such as locally composed songs and variants of “Barbara Allen,” “The Little Mohee” (or “Lassie Mohee”), and other widely disseminated ballads, a few of which are still sung. Harper also documented hollering or yodeling, a distinctive alternation of head and chest tones sometimes interspersed with song fragments, which was used to call hogs and cattle, to signal that an individual was returning home, or simply to have fun. This tradition is no longer widespread, although a few families maintain the practice. Country western and bluegrass bands have largely replaced old-time frolics and square dances.