Wiregrass country, named for its native tall grass (Aristida stricta), is a historic area of the South shared by south central Georgia, southeastern Alabama, and the panhandle of Florida. In wiregrass Georgia, folk-cultural traditions include a range of phenomena: folk art (quilting to yard decorations); festivals (peanut festivals to rattlesnake roundups); foodways (chicken pilaf to mullet); music and dance (shape-note singing to play-party songs); play and recreational activities (fireball to fishing); occupational lore (turpentining to shade tobacco); vernacular architecture (shotgun houses to tobacco barns); and religious observations (Baptist Union meetings to funerary customs).

Ecosystem

Wiregrass folklore owes much to its ecosystem. Associated with the longleaf pine forest, wiregrass grows within a fire ecosystem. This wiregrass ecosystem, moreover, produces a high incidence of low intensity fires as one of its fundamental natural processes. Residents came to regard these fires as a tool to control their environment, and the wiregrass itself helped foster a particular lifestyle. It occurs, for instance, as a prominent motif in the region’s oral tradition. Storytellers often incorporate it as part of the setting for their narratives of personal experience. In its unburnt state, wiregrass became an integral part of the terrain and served as cover for wildlife, a place where quail might nest or predators like rattlesnakes might lurk.

Rattlesnakes constitute another popular motif. A rationale for ritually burning the forest, unchecked rattlesnake populations represent a real threat to people. Personal experience narratives, as the prime prose narrative form of our times, frequently function as cautionary tales, warning about this potential threat. Several wiregrass Georgia towns (Claxton, Whigham) annually host rattlesnake roundups. These festivals shift public attention to the prevalence of this dangerous species, especially since local laws prohibit burning the woods without a special permit. Instead, communities sponsor roundups in which competitors literally capture hundreds of snakes. Every year, for example, as many as 20,000 people attend the parade and festival in Whigham (population 605). Claxton promotes its roundup as “the beauty with the beasts” competition: the judging of the snake competition occurs at the same time as the crowning of the Roundup Queen.

Most wiregrass towns choose a local theme for their festivals. In wiregrass Georgia, as in other places, festivals fulfill a social function while promoting tourism. Each town selects an item of regional interest in which it takes pride. Some wiregrass cities celebrate certain crops significant to their commerce. Morven holds a Peach Festival. Glennville’s Sweet Onion Festival faces competition from its well-established neighbor, Vidalia. Sylvester is known for its annual Peanut Festival at Possum Poke, its permanent festival grounds. The Mayhaw Festival in Colquitt is particularly distinctive. The mayhaw fruit grows almost exclusively in wiregrass country and is ripe only during three weeks in the spring. Other festivals, such as Mule Day in Calvary and Swine Time in Climax, fete animals important to the region’s past and present development.

Social Activities

Historically, wiregrass residents found their own, often raucous, forms of entertainment. Accustomed to working hard and playing hard, farmers and their families traditionally engaged in get-togethers—husking bees or corn shuckings, cane grinds or sugar boilings,”pindar” (peanut) shellings and boilings, and hog killings. Quilting parties and sewing bees offered women opportunities for social interaction. Wiregrass residents played a folk game called fireball, in which the “ball”consisted of a burlap sack or rags tied together with a fine rope, soaked in kerosene, and set on fire. Hordes of neighbors would gather and form sides for a harmless game of hurling these missiles at one another, spectacularly lighting up the nighttime skies.

Residents continue to enjoy fishing and hunting in the many creeks, streams, and pristine forests of the wiregrass region. Fishing in particular is upheld as a so-called poor man’s sport, since it can be pursued without much expense. Those who like to fish refer to it as “drowning worms.” Over the years they have developed several ingenious ways of procuring bait. One is the practice of grunting worms, or worm fiddling: driving a stick into the ground and rubbing a stone back and forth to make the stick vibrate, which lures worms out of moist soil.

On the other end of the spectrum, the Thomasville area gained renown for its elite woodland hunting plantations. Owned by northern industrialists after the Civil War (1861-65), the large estates recognized quail as the quintessential game bird in wiregrass Georgia. These properties were self-contained, frequently having their own roads, schools, and churches. Quail season attracted many celebrities, including presidents and royalty. The hunting season abounded with rituals, with the best saved for last. On the closing day, workers “put the fire” to everything, inducing a controlled burn of the woodlands. Ironically, it was the near depletion of the quail population that first alerted conservationists to the role of fire in the evolution and regeneration of the pine forest.

Religion

One cannot talk about everyday life in wiregrass Georgia without discussing religion. One of the earliest schisms involved a nationwide rift among the Baptists regarding foreign missions—a dispute that coincided with the arrival of many early pioneers in wiregrass country. A particular faction, the antimission Primitive Baptists, emerged in the area. Because of the restrictions they placed on members, the Primitive Baptists gained the label “hardshell.” Dancing and drinking were forbidden, of course, but one could also be expelled for playing an instrument at dances or for handling alcoholic beverages. There were also sanctions against profanity, dishonesty, and backbiting that produced grievances. Although restrictions applied to dancing, play-party songs were permitted, allowing members to sing and essentially to dance without incrimination. Such songs and ring games functioned as a favorite pastime of both adults and children.

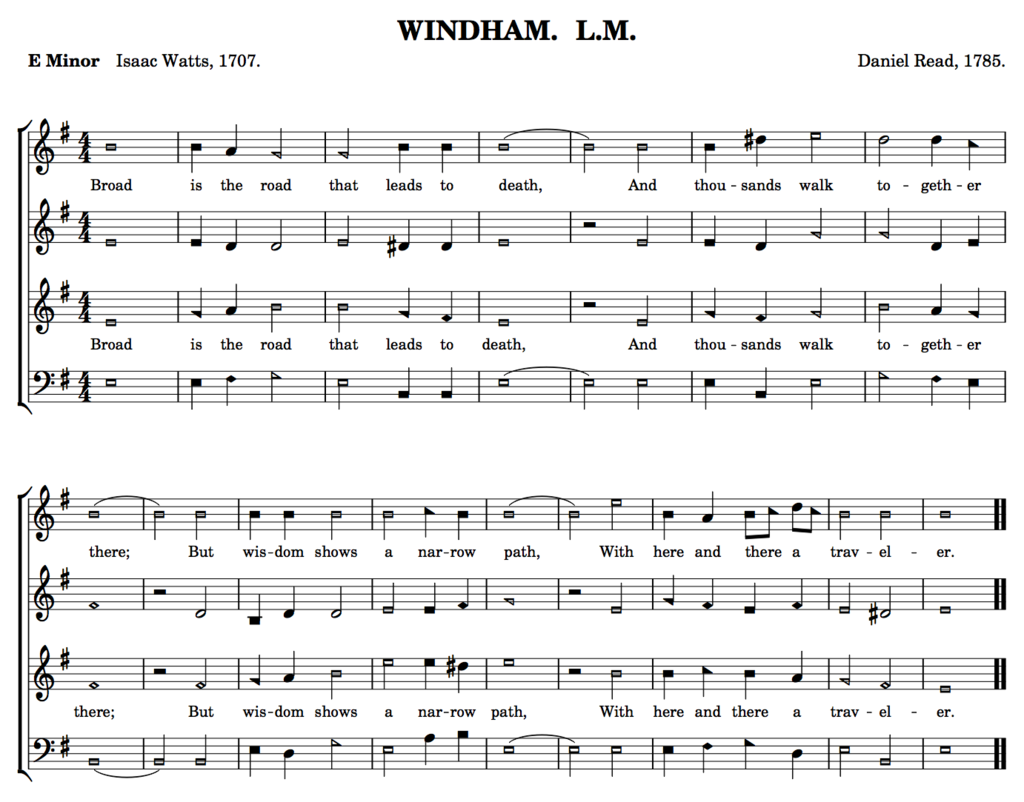

Another significant wiregrass country tradition embraces a form of religious music known as Sacred Harp. This musical tradition dates back to late-eighteenth-century New England but has been most enduring in the South. In singing schools based on the fasola singing tradition, participants learned to sight-read notes originally based on four shapes (triangle, circle, rectangle, and diamond). Forming a square seating arrangement, they sang in four-part harmony (treble, alto, tenor, and bass). As the tradition evolved, singers switched to a seven-shape note system. Song book publishers began to sponsor professional duets and quartets to attend these “all-day sings.” Waycross is known for maintaining the tradition of all-night gospel sings, highlighting the role sacred music plays regionally as a form of entertainment and an evangelical tool.

The tune "Windham" as it appears in The Sacred Harp, 1911 edition. Image from Wikimedia.

Special church services and singing conventions still occasion what is known as dinner on the grounds. At these all-day events, a midday break results in a virtual feast, often featuring some of the region’s most popular food dishes. Especially popular is the lemonade that quenches one’s thirst after a long morning of singing or preaching; traditionally it was prepared by the menfolk in large barrels. Churches and other community organizations often serve chicken pilaf, a festive food. Their fish fries frequently emphasize mullet, a saltwater fish that, farther inland, is considered a delicacy to be eaten in colder months. These are some of the folk cultural traditions, many of which still prevail, in wiregrass Georgia.