In any given period of history, most people living in the same place and sharing a common culture prefer that their homes be laid out in ways considered appropriate or fashionable at that time. Their choices in residential design, such as the preference for striking horticultural displays characteristic of many late-nineteenth-century landscapes, give expression to personal and communal values. Such values evolve and change over the years as new interests, ideas, or needs inspire alternative forms of design expression for subsequent generations of designers and homeowners.

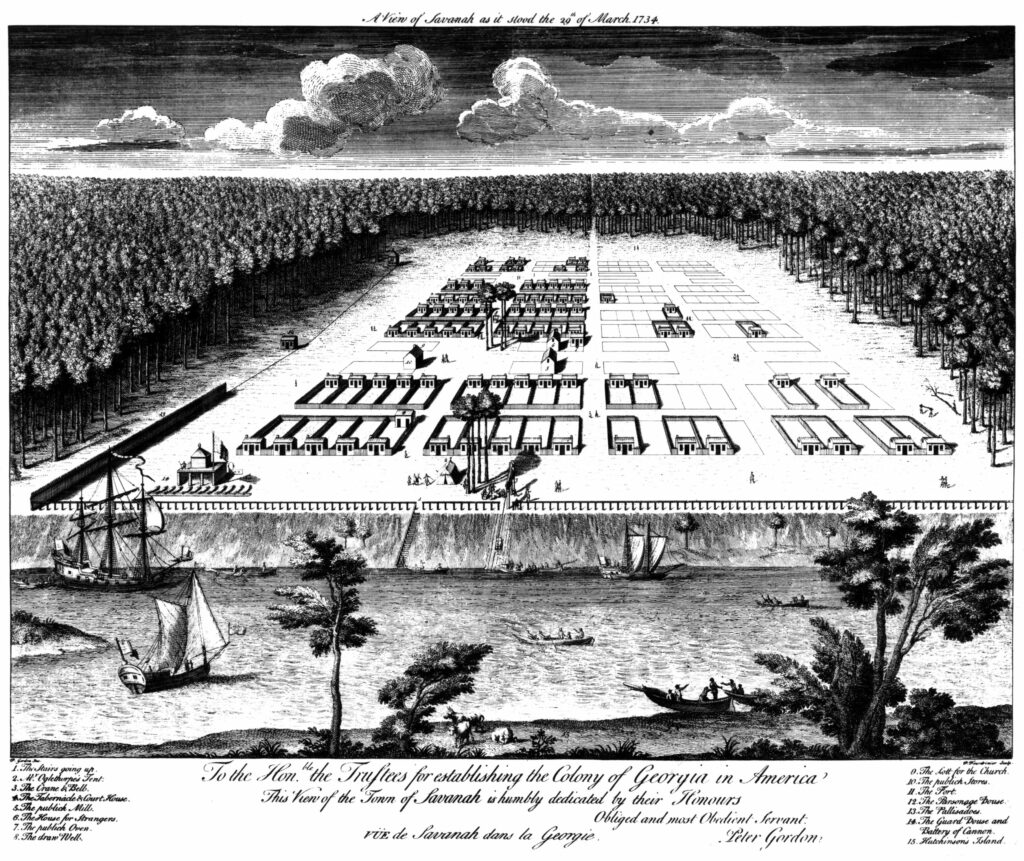

The distinctive traditions of landscape design in the South developed as a response to the particulars of geography and climate, as well as to a range of social, economic, and political institutions that informed southern identity and experience. This largely conservative regional tradition favored stylistic models derived, however remotely, from European Renaissance and baroque practices. Thus, while the neat, small yards of the first Georgia colonists, illustrated in the 1734 engraving “A View of Savannah as it Stood the 29th of March, 1734,” suggest the democratic idealism of the Trustees’ charter for the colony, they also reflect the imposition of European ideas about order and civilization on the threatening disorder of wild nature.

Working Yards and Gardens

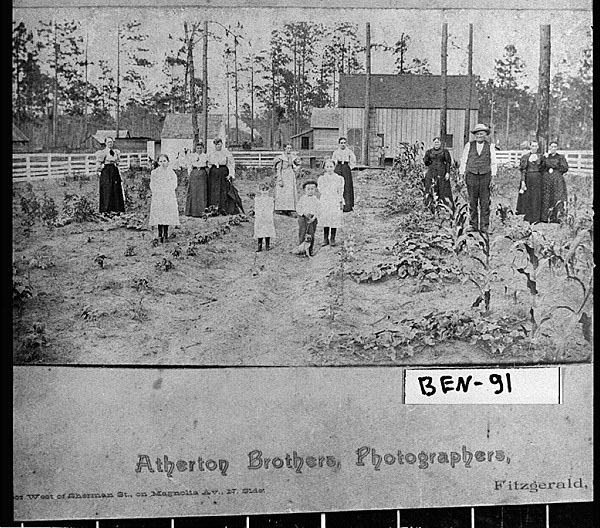

The earliest domestic yards represent a type of vernacular landscape that remained continuous over time and place throughout Georgia well into the twentieth century. The yards primarily functioned to accommodate the essential activities and structures of rural living: gardening, slaughtering, cooking and other kinds of food processing; laundering; storage sheds and cellars; and pens, coops, or stables. The use of fencing to enclose the house lot, gardens, and other zones of activity was a universal feature of such yards and contributed to an overall appearance of geometric ordering. Entrance paths most often were centered along the axis of the entrance hall of the house. Even if the landscape elements lacked a symmetrical arrangement, there was usually a fairly formal disposition of parts within the whole.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

Courtesy of Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries.

The gardens associated with working yards combined the functions of a medieval kitchen and a physic garden, producing an assortment of vegetables, greens, and herbs for the table, as well as medicinal plants. The same traditions of practice determined the layout of the garden, which was usually a gridded arrangement of raised rectangular planting beds with walks between and borders running the length of the perimeter fencing. When well kept and flourishing, gardens of this type were also pleasing in appearance and offered evidence of the household’s industry.

A common elaboration of the vernacular yard was the “swept yard,” which drew upon the same aesthetic of neatness and conspicuous care. The sand or clay surfaces of such yards were regularly swept or raked to remove grass or weeds and, in some instances, to maintain a pleasing decorative pattern on the ground.

Ornamental Gardens and Landscapes

Even in the eighteenth century wealthy Georgia landowners appreciated the potential of more ambitious, high-style forms of landscape design to enhance the value of residential properties. Their house lots in town and on rural plantations were graced with gardens in which ornamental flowers and shrubs were carefully tended, and such embellishments as parterres, gazebos, fountains, and statuary offered visual and sensory pleasure. Beyond the walls or fences of these formal gardens, the grounds of fine country houses boasted tree-lined arrival drives, spacious lawns, and wooded groves in the fashion of the English school of landscape gardening.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

By the middle of the nineteenth century, progressive southern agricultural journals were encouraging those of more modest means to beautify their homesteads by adding flower beds, shrubberies, and trees to the landscape. Some Georgians were attracted to the ideas promulgated by the northern horticultural writer Andrew Jackson Downing, who proposed that house and landscape together should constitute a charming scenic composition, either serenely beautiful or strikingly “picturesque.” Downing’s formulas influenced the emergence late in the century of a national style, labeled “Victorian” in common parlance and identified with designs that favored complexity, variety, and dramatic effect in the forms and materials of residential yards, whatever the scale. Examples of the style survive today and include the Azalea Inn, Hamilton-Turner Inn, and Magnolia Place Inn, all in Savannah.

Courtesy of Explore Georgia.

Although suburban development in Georgia was delayed by the lingering economic consequences of the Civil War (1861-65), the drive for a more prosperous “New South” culture and the proliferation of magazines devoted to house and garden design early in the twentieth century further contributed to the dominance of national landscape models. The involvement of the preeminent American landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted in the early planning of Atlanta’s Druid Hills neighborhood signaled an acceptance throughout the region of the concept of parklike suburban communities, in which individual properties were visually unified along curving streets by contiguous sweeps of lawn and canopies of shade trees. Even as wave after wave of architectural change marked succeeding decades of the century, most residential landscape design, at least in front yards, drew upon this tradition.

In the years following World War II (1941-45), however, new technologies removed the last traces of the working landscape from backyards, while the movement eastward of California modernism influenced both landscapes and lifestyles, changing the perception of the residential landscape to that of a private oasis for entertainment, leisure, and play.