Vernacular gardens, by definition, are gardens of ordinary people, not those designed by professionals or owned by the elite. The vernacular garden is a result of community-held beliefs about gardening aesthetics and utility as well as the traditional use of space and how it should function.

A General Homestead Plan

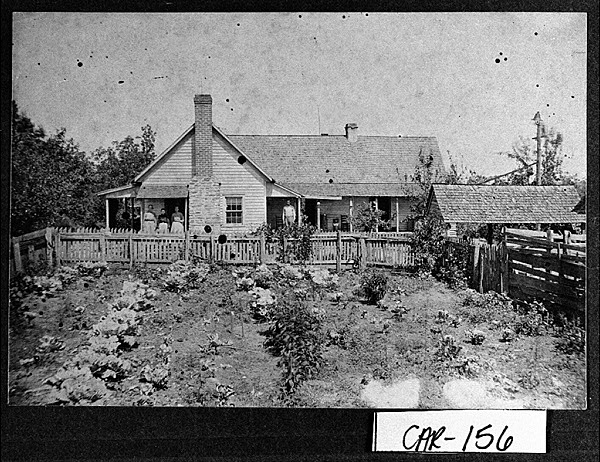

An early Georgia farmer’s homestead was, above all, functional. Farmyards were designed according to use rather than aesthetics. Folkways, the zodiac, weather, the settler’s country of origin and ethnicity, and the almanac were among the factors guiding the placement of the outbuildings and gardens. For example, the main house was usually situated on a rise, with good drainage and easy access to a source of fresh water. The outbuildings, including a kitchen, springhouse, root cellar, and corn crib, were most often placed to establish an open space between the main house and the smaller buildings. Many household chores—for example, clothes washing and horseshoeing—were performed in this space, called a dooryard.

Some southern regional generalities can be seen, but no set pattern in Georgia becomes evident, other than a distinction between coastal and mountain locales. In the rolling hills of north Georgia, dooryard paths were often lined with privet hedges to prevent erosion, but in the lower regions of the state, the yard was traditionally swept bare to avoid giving snakes and other pests a place to hide. In the twentieth century, with the advent of the lawnmower, the dooryard evolved into a grass lawn.

No description of a southern rural farmhouse can omit the porch—a shady place to work and rest in a hot climate, as well as a means of cooling the interior of the house. The porch railings would sport containers of houseplants or colorful annuals planted in unserviceable household vessels. Front pathways to the porch were often lined with white-painted river rocks, lighting the way in the moonlight.

Until the early 1900s such foraging animals as chickens and hogs were allowed to roam in the wild, while prized animals like horses, mules, and milk cows were housed and fenced. Fences around gardens were designed to protect the plants from foraging farm animals. In the twentieth century fence regulations required penning all animals in an enclosed space or field. This encouraged the creation of the open front lawn and the planting of roadside trees. The shrubs and flowers also tended to echo the fence lines, forming a reverse enclosure. Colorful flowers were often planted in a fenced plot in rows (known as “lining out” a bed), near the side or rear of the house.

Scuppernong or muscadine grapes were grown to be used for juice, preserves, and in some homes, wine. Most Georgian rural homesteads had some type of arbor for the greenish red scuppernong or the blue-black muscadine grape. The arbor, built very high, was located to receive full sun at the side of the house or barn and to provide a screen for some of the less attractive outbuildings. Today, the grape arbor is one of the most important clues for identifying a vernacular garden of the rural South.

Orchards were planted close to the house as well. Pears, peaches, figs, pomegranates, and damson plums, also known as “bullace,” were pollinated by bees, usually kept in hives along the fence bordering the orchard.

Women’s Roles in the Garden

Women of all races and cultures shaped vernacular gardens. Before European settlement of Georgia and the Southeast, Native Americans had tended the landscape for centuries. Native American women are mentioned in travelers’ writings as being responsible for planting and maintaining crops in fields that had been prepared by the men. Many prehistoric foodstuffs and, of course, the gardens have been lost to modern taste, but corn, beans, squash, gourds, sunflowers, and tobacco are legacies of their gardening expertise.

European Americans also worked according to an accepted division of labor. For women in rural Georgia, the traditional role was to plant, tend, and use the “kitchen” gardens and yards. This was distinct from the masculine role, which was to care for the large acreage of crops and numerous animals.

The European origins of the white farmer’s wife, who began a homestead on a more or less wild plot of land, influenced what types of plants she put in the ground and where she planted them. Seeds, carefully protected and carried from other long-lost homesites, and hardy cuttings of shrubs and trees were planted near the door of the house. Plants were scouted from the wilderness surrounding the farm’s clearing. Fruit trees, vegetables, and beehives were placed around the perimeter of the clearing. The women of the family were subsequently responsible for harvesting the fruit and vegetables and preserving them. Gardens raised by white rural settlers tended to reflect their practical outlook: an occasional whirligig or gourd birdhouse might be evident in the neatly cl ipped yards, but the overall appearance was generally utilitarian.

Various descriptions of enslaved peoples’ quarters and plantation life document garden plots in which those enslaved raised produce to supplement their diets. Most often tended by women, who could not depend on men to be available, the garden provided an area of self-reliance. This independence was carried forward upon emancipation. The garden practices and traditions learned in slavery were handed down orally to subsequent generations.

Richard Westmacott, the author of African-American Gardens and Yards in the Rural South, identifies three major functions of the rural garden for free African Americans: its contribution to subsistence; its utility as a kitchen extension for household chores; and its use for entertainment, recreation, and display. He mentions the creative use of found objects as yard art and for edging, plant containers, and stands. Bricks, bottles, tires, pots, and recently, even washing machines were not lost to a Black woman’s gardening eye. Westmacott also describes as distinctly African American a sensitivity to the spirituality and religious symbolism of the garden. Often, plants were used to commemorate a lost loved one or to establish a visual memorial. Another distinctive attribute of African American gardens was a love of riotous color and the mixing of vegetables and ornamentals in the same bed. The beds were not normally “lined out,” or planted in straight rows, but planted in groupings where they would best support the landscape.

Vernacular Gardens Today

The heritage of a handed-down culture of gardening in the rural South, both European and African American, can be characterized as coming from folk or nonscholarly sources. These rural gardening traditions have been the farmer’s basis for adapting and viewing the spatial functioning of a dooryard from the last century to the present. The layout of today’s southern farms is based on these cultural principles, and an observant traveler can still see the characteristics of a folkway landscape in the rural areas of Georgia.