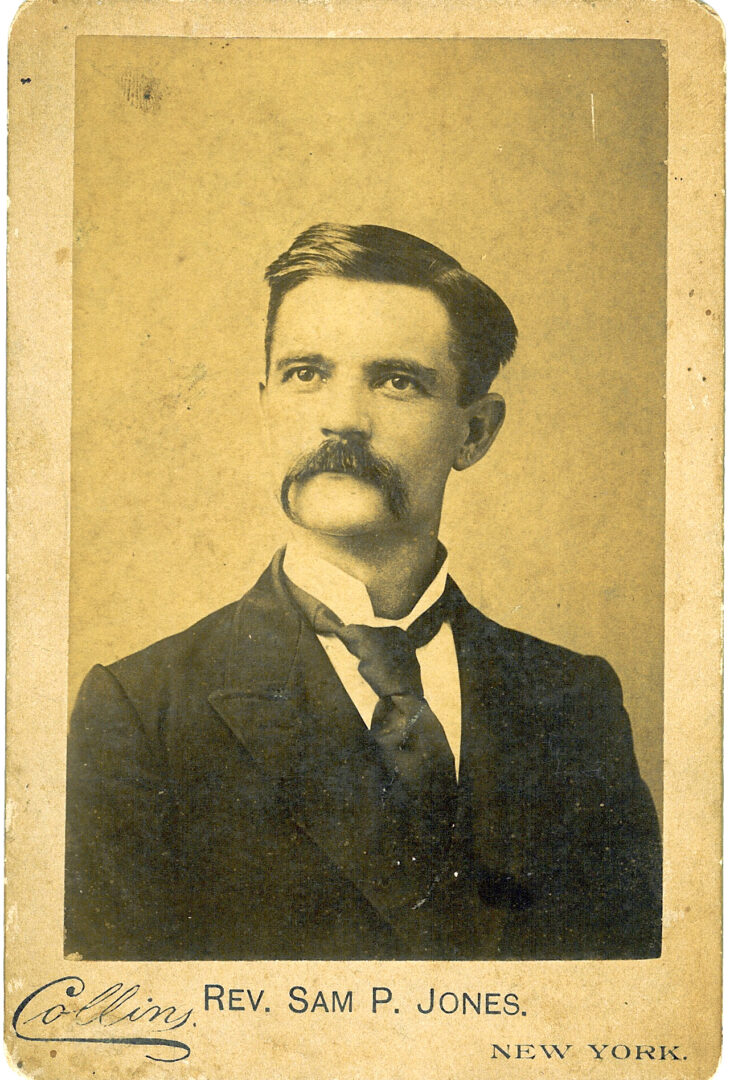

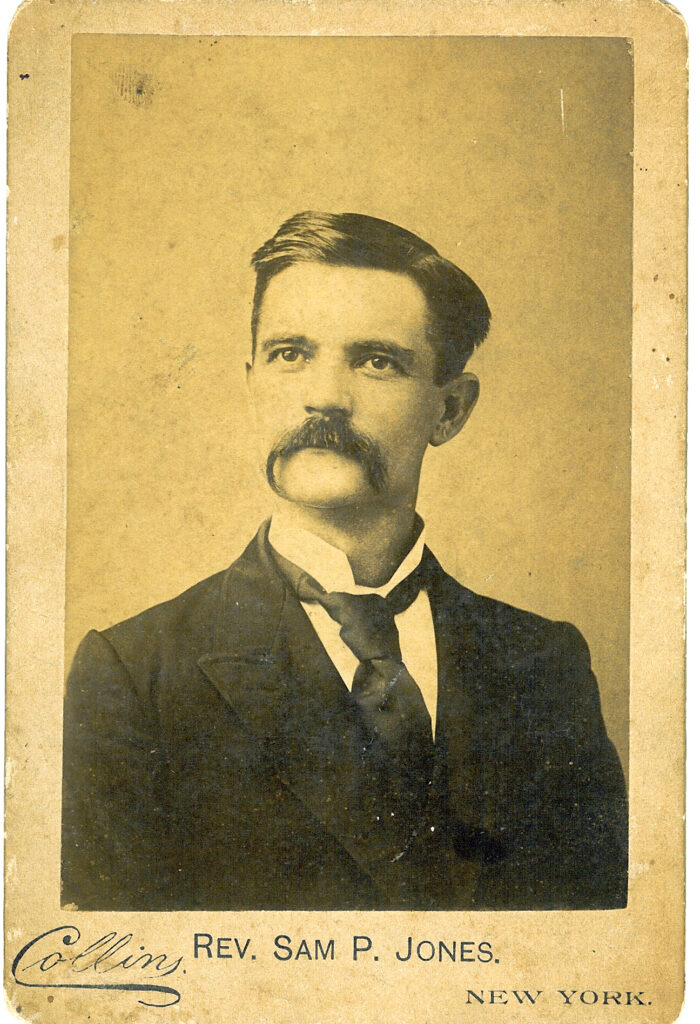

With his plain style and simple “quit your meanness” theology, Sam Jones was the South’s most famous preacher in the late nineteenth century.

Early Life

Samuel Porter Jones was born October 16, 1847, in Oak Bowery, Alabama, the son of Nancy “Queenie” Porter and John J. Jones, a lawyer and businessman. After his mother’s death in 1855, Jones moved with his family to Cartersville, Georgia, where he grew up and lived for most of his life.

In the words of biographer Kathleen Minnix, Jones was “the product of generations of Methodist inbreeding”: his great-grandfather, grandfather, and four uncles were Methodist ministers. But it was not obvious that Jones would follow in the family tradition. He briefly studied law and was admitted to the Georgia bar in 1868, shortly before he married Laura McElwain of Kentucky, where he had spent the last days of the Civil War (1861-65).

Jones’s promising law practice was soon in shambles, however, because of his drinking problem. He soon was reduced to menial labor, stoking furnaces and driving freight wagons. In 1872 Jones promised his father, who was on his deathbed, that he would quit drinking—a promise kept (with a few lapses) for the rest of his life. As he struggled to quit drinking, Jones also underwent a religious experience that convinced him to enter the ministry.

Evangelistic Career

Jones was accepted by the North Georgia Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South, and began his ministry with the Van Wert circuit, a group of five churches spread over four counties. He refined his natural talent for preaching and within a couple years was being asked by nearby preachers to hold special services for them. By the late 1870s he spent as much time at other churches as at his own.

Realizing Jones’s talents, the conference appointed him as the fund-raising agent for the Methodist Orphan Home in Decatur. Jones moved his family back to Cartersville (he and his wife had seven children, one of whom died as a baby), and he began traveling the state to raise money for the orphanage.

Jones supplemented his fund-raising with revival services. As his oratorical skill grew, so too did his reputation. A revival in Nashville, Tennessee, in 1885 put Jones in the national limelight: a three-week series of meetings attracted thousands of people and was covered by the press from Boston, Massachusetts, to San Francisco, California.

It was in Nashville that Jones won his most famous convert, Tom Ryman, whose riverboats carried not only a large share of Nashville’s river trade but also barrooms, gambling casinos, and dancing girls. Jones converted Ryman, who in his newfound religious zeal decided to clean up his boats and construct a building where Jones and other preachers could hold revivals. Ryman’s Union Gospel Tabernacle later became”the Mother Church of country music,” the home of the Grand Ole Opry. The Nashville revival led to the most frantic year of Jones’s life. From September 1885 to September 1886, he preached, by his own estimate, 1,000 sermons to 3 million people around the country. He was seldom home for more than a few days at a time.

Having made his mark in the year after the Nashville revival, Jones vowed that he would stop accepting every single preaching opportunity that came his way. He slowed down a bit, but for the next twenty years he was on the road more than he was at home in Cartersville. Jones preached in Baltimore, Maryland; Boston, Chicago, Illinois (where in five weeks he preached to a quarter of a million people); Cincinnati, Ohio; Indianapolis, Indiana; Kansas City, Missouri; Los Angeles, California; Minneapolis, Minnesota; New York City, Omaha, Nebraska; St. Paul, Minnesota; Toledo, Ohio; Toronto, Canada, and dozens of other cities. By the end of the 1880s, he was, with the possible exception of Dwight Moody, the most famous preacher in America.

Jones’s Message

Jones’s message was a simple one: “Quit Your Meanness.” He was famous for his distaste for religious doctrine, preferring instead the simple directive of living a good life that was as sin-free as possible. He preached against the theater, “dime” novels, playing cards, baseball, and dances. His biggest campaign, though, was against alcohol. “I will fight the liquor traffic as long as I have fists, kick it as long as I have a foot, bite it as long as I have a tooth, and then gum’em till I die,” he said.

His preaching style suited his message. He was humorous and crude, high-strung and theatrical—not at all what many people expected from a preacher. “Just plain 'Sam Jones,'” as he liked to be known, was unpretentious, aiming at (or often below) his audiences’ educational and social level. “We have been clamouring for fifty years for an educated ministry,” he said, “and we have got it to-day, and the church is deader than it ever has been in its history. Half of the literary preachers in this town are A.B.’s, Ph.D.’s, D.D.’s, LL.D.’s, and A.S.S.’s.”

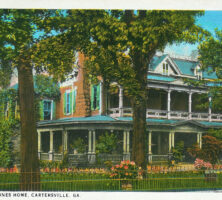

Jones died suddenly on October 15, 1906, a day shy of his fifty-ninth birthday, while returning home from a revival in Oklahoma City. He was taken first to Atlanta, where his body lay in state in the rotunda of the capitol, and then to Cartersville, where he was buried in Oak Hill Cemetery. Jones’s Victorian home in Cartersville is now maintained as the Rose Lawn Museum in honor of both Jones and his fellow Georgian from Bartow County, Rebecca Latimer Felton.