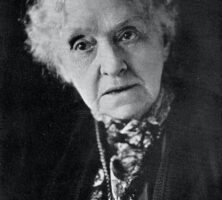

Rebecca Latimer Felton was one of the South’s leading advocates for women’s rights and also one of its most outspoken proponents of lynching. At the end of her long life in 1930, she was remembered as an accomplished writer, a tireless campaigner for Progressive Era reforms, and the first woman to serve in the U.S. Senate.

Rebecca Ann Latimer was born on June 10, 1835, the daughter of Charles Latimer, a DeKalb County plantation owner and enslaver, and his wife, Eleanor Swift Latimer. When the young Latimer graduated, at the top of her class, in 1852 from Madison Female College in Madison, the commencement speaker was William H. Felton, a recently widowed state legislator, physician, Methodist minister, and slave owner in Bartow County. A year later the valedictorian and the speaker were married, and Rebecca Felton moved to her husband’s plantation, just north of Cartersville. Of the five children born to the couple, only one, Howard Erwin, survived childhood.

“The Political She of Georgia”

In 1874 William Felton ran for the Seventh Congressional District seat from Georgia as an Independent Democrat. He had been a Whig before the Civil War (1861-65), as had the Latimers, and neither he nor Rebecca Felton, who served as his campaign manager, cared for the so-called Bourbon Democrats who had taken control of the state in the early 1870s. William Felton won that election and then the next two, serving three terms (1875-81) in the U.S. Congress. From 1884 to 1890 he served another three terms in the state legislature.

Rebecca Felton entered the public arena through her husband’s political career and soon became more than just a campaign manager. She polished his speeches and wrote dozens of newspaper articles, both signed and unsigned, on his behalf. She helped draft the bills that he introduced in the state legislature. In 1885 the Feltons bought a Cartersville newspaper, which she ran for a year and a half to promote her husband. She was undoubtedly his biggest and most effective supporter. William Felton’s constituents sometimes bragged that they were getting two representatives for the price of one. Not everyone liked the arrangement, however. A fellow legislator, speaking from the assembly floor, called Felton “the political she of Georgia,” an unflattering characterization that greatly angered the husband and wife team.

Until late in her life, Felton herself saw her career as tied completely to her husband’s. In 1911, two years after his death, she published My Memoirs of Georgia Politics, a long and tedious volume, written, according to the title page, by “Mrs. William H. Felton.” The book details her husband’s political battles, denouncing those who worked against him. Perhaps more than she realized, the years with her husband developed her political skills and introduced her to the friends and enemies that would define much of the rest of her political life. Chief among these was her lifelong animosity toward John B. Gordon, the Confederate general turned politician and businessman who had, she felt, worked against her husband for his own selfish gain. In her scrapbooks she kept letters, clippings, and other items detailing the Feltons’ battles with Gordon and others, annotating them with remarks such as “consummate liar” and “lest I forget.”

Although Felton never rose completely above these personal animosities, her career after her husband’s retirement in the 1890s (about the time she turned sixty) was marked more by her own desires for reform. Through speeches and her writings, she helped to effect statewide prohibition and to bring an end to the convict lease system, a system of leasing cheap labor to private companies, which often maintained the convicts in substandard and even inhumane conditions. Both were achieved in 1908. She defended the state university against its opponents—the church-affiliated colleges and those who felt that the state’s limited funds should be directed toward improving public schools below the college level. She also spoke out, to chapters of the United Daughters of the Confederacy and others, for vocational education opportunities for poor white girls in the state. Not until the early twentieth century did Felton embrace the reform with which she is most associated: woman suffrage. She became the South’s best known and most effective champion of women’s right to vote. In 1915 writer Corra Harris, a fellow Georgian, published a novel about woman suffrage entitled The Co-Citizens, which features a protagonist based loosely on Felton.

“Then I Say Lynch”

While she was a crusader for progressive reform, Felton was also one of the South’s most vocal supporters of lynching. In 1897, Felton delivered a speech to the Georgia State Agricultural Society titled “Woman on the Farm.” The speech, which Felton gave in many different settings over the 1890s, encapsulated her views on gender and race as well as her fears of miscegenation. On the one hand, she urged the state to provide more educational opportunities for white women; on the other, she advocated the lynching of Black men to protect white women from rape. Citing several newspaper reports of interracial rape, she faulted the institutions of the South, and especially white men of influence, for failing to protect white women’s “innocence and virtue.” In closing, Felton said that if lynching would “protect woman’s dearest possession from the ravening human beasts – then I say lynch, a thousand times a week if necessary.” This line would be repeated by the press and Felton herself in the following years.

In 1898, Alexander Manly, editor of a Black-owned newspaper in Wilmington, North Carolina, responded directly to Felton’s speech. Among other things, Manly pointed to the prevalence of interracial sex throughout the South’s history, including those instigated by white men and willingly engaged in by white women. White Democrats in North Carolina held up the editorial as an example of the perils of Black political power, using it as a pretext to carry out an insurrection and racial massacre in Wilmington. Felton viewed the events as confirmation of her stance, and thought that Manly – or anyone who suggested actual intimacy across the color line – should be “made to fear the lyncher’s rope.” She condemned anyone who dared to question the South’s racial policies; when Andrew Sledd, a professor at Emory College, did just that in an article published in 1902 in the Atlantic Monthly, she was instrumental in forcing his resignation from the school.

In 1899 Felton began writing for the semiweekly edition of the Atlanta Journal, an edition started by publisher Hoke Smith to appeal to the state’s rural readers. “The Country Home” was a far-ranging column that included everything from homemaking advice to Felton’s opinions on almost anything. One historian described it as “a cross between a modern-day 'Dear Abby’ and 'Hints from Heloise.'” The column, which continued for more than two decades, provided the most direct link rural Georgians had with Felton.

The First Woman Senator

Felton also held the distinction of being the first woman in the U.S. Senate. When Senator Thomas E. Watson died on September 26, 1922, Governor Thomas Hardwick appointed a replacement to serve until a special election could be held. Hardwick pointed out that his appointee would not actually “serve” because Congress was not in session when Watson died, and the next session would not begin until after the special election.

Hardwick himself wanted to be a senator, and he knew that the person he appointed would have a real advantage (as incumbent) in the special election. So rather than give an edge to a potential opponent, and to get on the good side of Georgia’s newly enfranchised women voters (whom he had offended by opposing the Nineteenth Amendment), Hardwick appointed the eighty-seven-year-old Felton on October 3.

Hardwick lost the special election two weeks later to Walter F. George. When the session opened George allowed Felton to present her credentials before he claimed his seat. She was sworn in at noon on November 21. The next morning she made a speech thanking the Senate for allowing her to be sworn in and noting that the women who followed her would serve with “ability,” “integrity of purpose,” and “unstinted usefulness.” Senator-elect George was then sworn in. Felton’s term had lasted for just twenty-four hours.

Rebecca Felton’s legacy speaks to the twisted ideology of race in the Jim Crow South. Although she was very progressive in many ways, her racist views advanced white supremacy and provided justification for heinous acts of racial violence. She died on January 24, 1930, and is buried in Cartersville’s Oak Hill Cemetery. The Rose Lawn Musuem in Cartersville honors the memory of Felton as well as that of Sam Jones, the well-known nineteenth-century preacher from Bartow County.

In 1997 Felton was inducted into Georgia Women of Achievement.