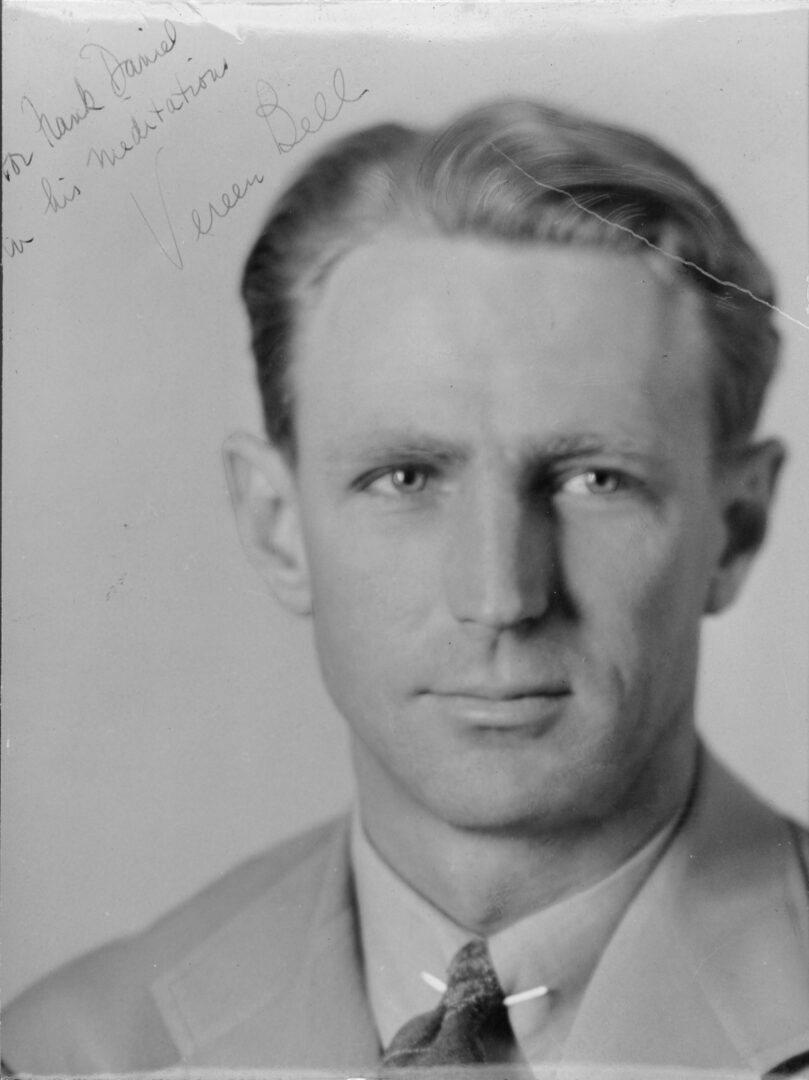

The first novel by Vereen Bell, Swamp Water was published initially in serial form in the Saturday Evening Post in November and December 1940, and then in book form by Little, Brown in February 1941. It was an immediate sensation in the South and across the nation. Bell, a native of Cairo, Georgia, edited American Boy-Youth’s Companion during the late 1930s, and returned home in 1940 to write fiction full-time. Swamp Water made him a wealthy man. The narrative, which concerns the exploits of a young boy, his hunting dog, and a fugitive hiding out in the Okefenokee Swamp, was so appealing that Bell was able to sell the movie rights to Twentieth Century Fox for $15,000. The studio made the film in the summer of 1941 and premiered it in October in Waycross. Swamp Water and its author are often lauded in south Georgia for bringing recognition to the area and “international fame” to the Okefenokee Swamp.

The Novel

Swamp Water is the engaging, fast-paced tale of Ben Ragan, a boy on the verge of manhood who chases his hunting dog, Trouble, into the Okefenokee Swamp against his father’s orders. While within the depths of the swamp, Ben is captured by Tom Keefer, a notorious hog-stealer who fled to the swamp after killing his brother-in-law a few years back. The two agree to engage in a secret hunting and trapping partnership. This operation works well until the townspeople begin to suspect that the boy could not possibly collect so many skins on his own. The men of the town ultimately discover that it is Keefer who is helping Ben in the Okefenokee (Ben’s sweetheart, Mabel, reveals the secret in a petulant moment), and a posse sets out after the fugitive but is unable to find him in the morass.

Courtesy of Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries.

A series of incidents reveal Keefer’s innocence: it turns out that a pair of vicious brothers named Silas and Bud Dorson have been the ones stealing hogs, and Keefer’s sister confesses that Tom killed her husband in order to protect her. His name cleared, Keefer almost emerges from the swamp and into society, but the Dorsons and Jesse Wick (the brother of the man Keefer killed) are there to ambush him. In the aftermath of the firefight, Ben leaves Trouble with an injured Keefer and runs out of the swamp for help—and here the novel ends.

Swamp Water was a best seller in 1941 (its second printing came the same month as its first), and most reviews were positive. Edith Walton, writing for the New York Times Book Review on February 23, 1941, lauded Bell’s descriptions of the Okefenokee and pronounced the novel “above all a triumph of atmospheric writing.” A reviewer for the New York Herald-Tribune Books agreed, writing in March 1941 that “Mr. Bell knows his background, and his descriptions are remarkably evocative. He knows the birds and animals by name and by habit; he has an ear for the native vernacular. . . . This is a fine, artistic, and virile first novel.” Some reviewers thought that Swamp Water’s characters were inarticulate and thus very dull, but most emphasized that Bell’s writing style lifted the tale “above the category of the merely thrilling and picturesque.”

The Film

The dramatic atmosphere of Swamp Water and its engaging plot appealed to the producers at Twentieth Century Fox, and they worked quickly to capitalize on the popularity of the novel. The completed screenplay, written by Dudley Nichols from Bell’s novel, placed more emphasis on the love story—the middle-class girl Ben falls for in the novel becomes Keefer’s daughter in the film—and added “stock” southern characters like the comic sheriff and some slack-jawed yokels. The movie was the first American film to be directed by Jean Renoir, son of Impressionist painter Pierre-Auguste Renoir and an already famous and revered French director. Renoir insisted that he film some scenes in the Okefenokee itself, and traveled to south Georgia with the actor playing Ben (Dana Andrews), the dog playing Trouble and his trainer, a producer, a cameraman, and a small crew in late June 1941. The group stayed in Waycross and fraternized with many of the inhabitants. Bell visited and watched some of the shooting, and locals were used as doubles for most of the male characters in long shots taken at the edge of the swamp.

After the Hollywood crowd left, Waycross residents began to campaign to host the movie’s premiere. They besieged Twentieth Century Fox executives with requests, and even sent Darryl Zanuck and others live baby alligators with tags affixed to their necks saying, “Even the gators in Okefenokee went to the premiere in Waycross.” Zanuck gave in and notified Lamar Swift, manager of the two movie theaters in Waycross—the Ritz and the Lyric—that he could have the premiere, slated for October 23, 1941. Georgia governor Eugene Talmadge declared the day of the premiere “Swamp Water Day” in the state, and Waycross merchants decorated the streets and their stores. A parade, special dinner, and wagon-ride preceded the premiere. Vereen Bell was the guest of honor.

Moviegoers flocked to the premiere and then to theaters all over the South when the movie opened in limited release a week later. By the time Swamp Water opened in New York City in November, it was well on the way to becoming one of Fox’s biggest moneymakers for the year. Film critics were not so enthusiastic, however. The reviewer for the New York Times noted acerbically that “the fact that Jean Renoir’s initial screen exercise in this country was completed before he learned the ABC’s of our language will mitigate somewhat his responsibility for 'Swamp Water.'” Critics found the acting capable but the script insipid, “sentimental bosh” tricked out with “pretentious hokum.”

The studio, however, was pleasantly surprised at the response to the movie, particularly in southern markets, and approved a remake of Swamp Water ten years later. The Lure of the Wilderness, released in June 1952, received similarly dismal reviews from critics, who saw it as a “rather soggy remake” of the original and an obvious vehicle for the buckskin-clad body of Jean Peters, a Hollywood ingenue and wife of Howard Hughes.

Both the novel Swamp Water and its film version brought attention to south Georgia and to the Okefenokee Swamp at a critical moment in the region’s history. U.S. president Franklin Roosevelt had declared the swamp a Federal Wildlife Refuge by executive order in 1937, and local boosters were just beginning to shape an infrastructure and culture of tourism in the area. Vereen Bell’s fictional representation of the swamp’s allure and the film’s visual depictions of it helped to convert the Okefenokee from a place of local use to a site of national consumption.