Young John Allen was a Methodist minister and Georgia native who spent his adult life in Shanghai, China, as a missionary, educator, and publisher. Allen was part of a larger wave of missionary activity that began in China following that nation’s loss to Great Britain in the First Opium War (1839-42) and subsequent opening to foreigners.

Early Life

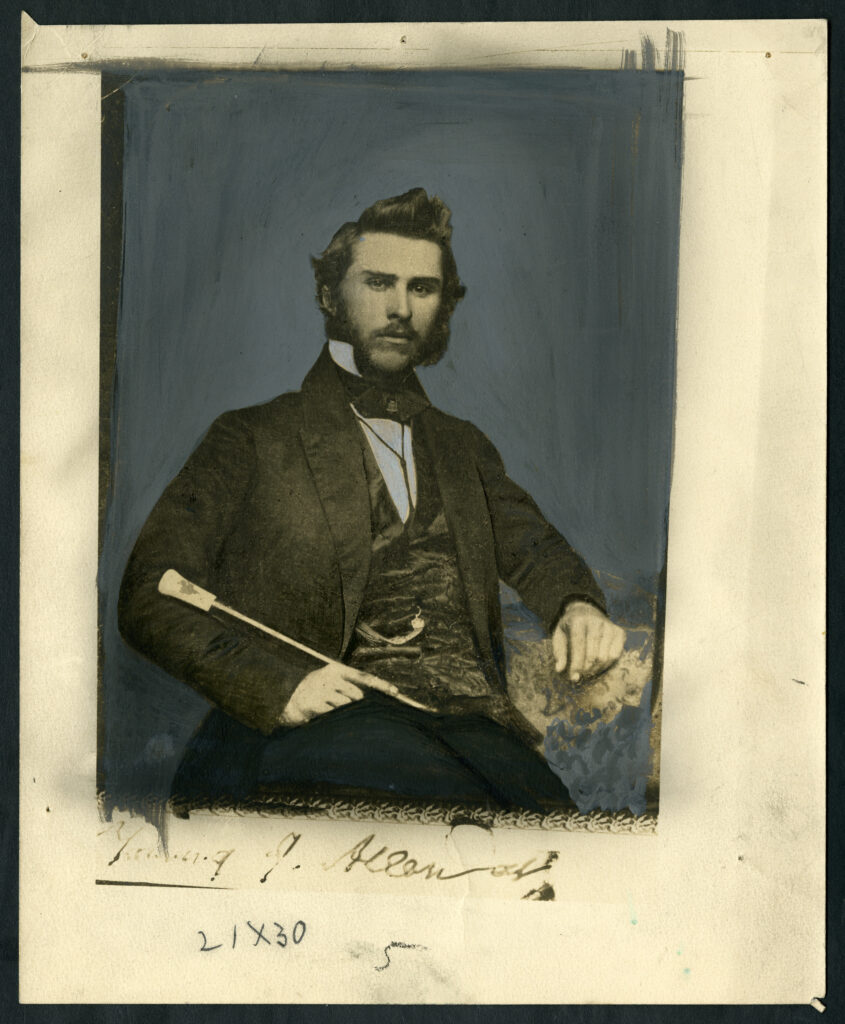

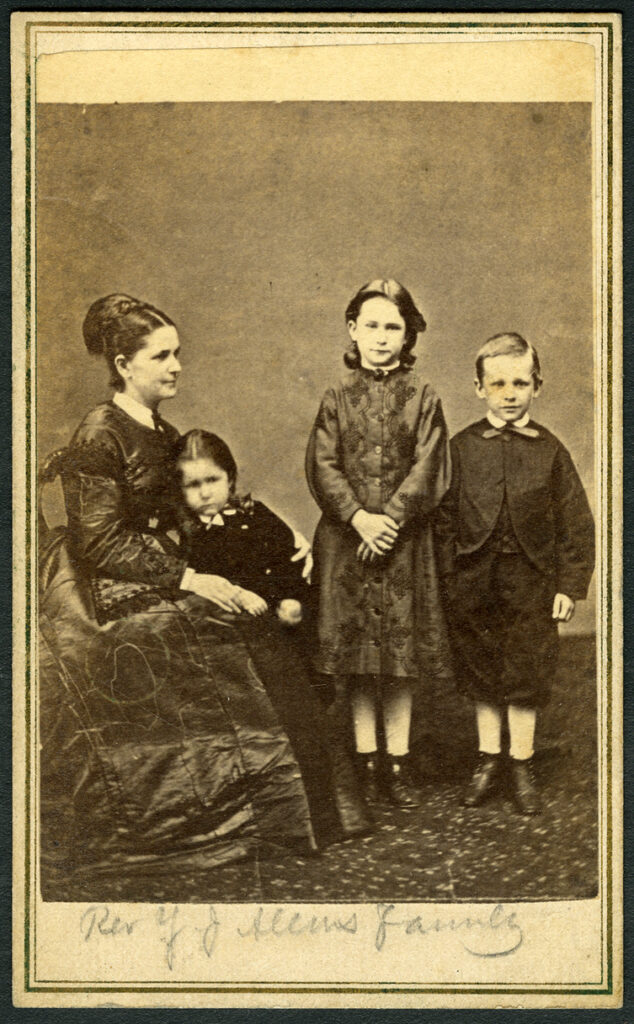

Allen was born in Burke County on January 3, 1836, to Jane Wooten and Andrew Young John Allen. His father, an educator and cotton planter, died before Allen was born, and his mother died soon after his birth, leaving him an orphan before he was one month old. His aunt and uncle, Nancy Wooten and Wiley Hutchins of Meriwether County, raised him, and their support, combined with Allen’s inheritance from his father, enabled him to attend Emory College in Oxford (later Oxford College of Emory University). Soon after he earned his undergraduate degree, Allen wed Mary Houston, a young woman educated at Wesleyan College in Macon. The couple had been making plans to travel abroad as missionaries for several years, and in 1859, just after the birth of their first daughter, Mellie, the family boarded a ship in New York City bound for Hong Kong. Allen owned land and at least two enslaved people in Georgia, all of which he sold to help fund his travel to China.

Missionary Life in China

In July 1860 Allen arrived in Shanghai to find a stagnant mission. He immediately established plans to build an itinerancy (the Methodist system of rotating ministers) in the region, and began seeking means to support it. Allen began his mission work exclusively as an evangelist, but after several years in Shanghai it became apparent that this strategy was not working. He and his fellow missionaries were not reaching the congregation numbers they desired, and those who did attend sermons often were not particularly receptive.

Almost as soon as Allen began his work, the Civil War (1861-65) erupted in the United States, resulting in a long spell of neglect from the home board; the mission received almost no funding for several years, and Allen and his colleagues worked civil positions and sold church land in order to survive. His employment at the Shanghai T’ung-wen Kuan (Government Anglo-Chinese School) during this time contributed to one of Allen’s most fundamental revelations: educated Chinese citizens and gentry were generally more receptive to Methodism than were others in the country. His goals shifted toward educating Chinese men and women; he particularly emphasized Western philosophy in the hope that doing so would help his Chinese students understand and accept Christian ideology.

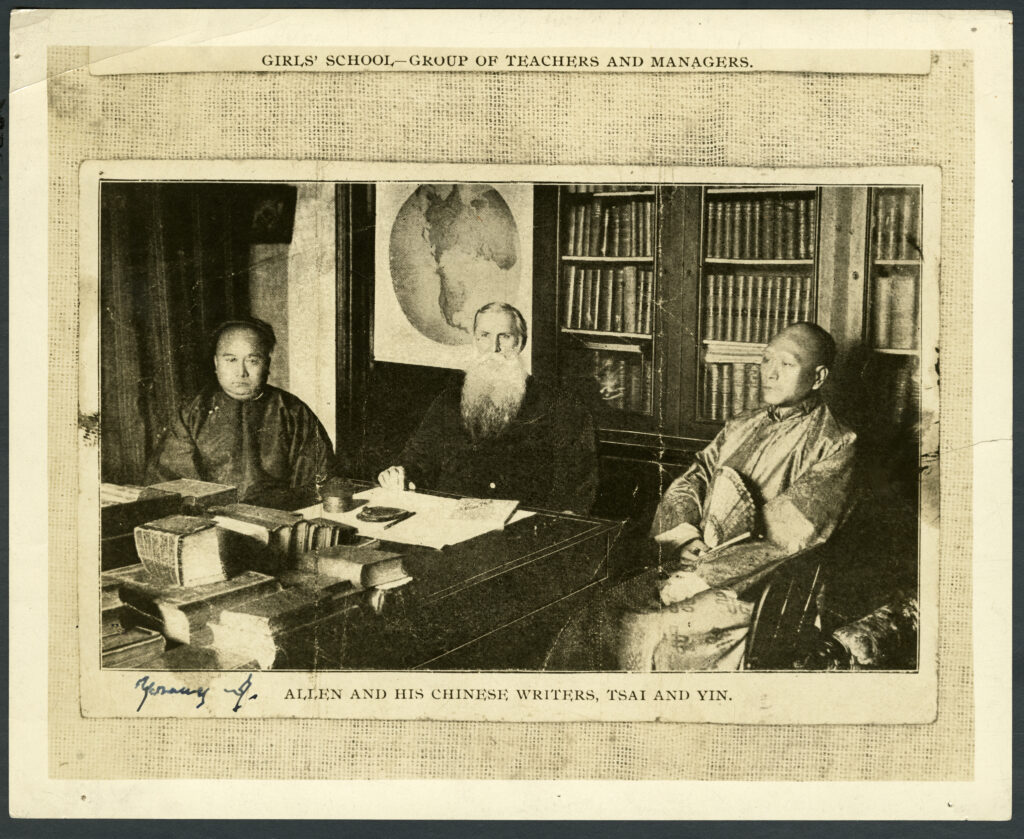

The second part of Allen’s crusade involved translating books and writing original essays aimed at convincing the Chinese to abandon their Confucian system, which he considered a hindrance to Christian conversion. The Confucian system’s communal ethos stood at odds with Christianity’s individualist concepts, and Allen understood that Chinese people would need to know other Western concepts in order for Methodism to make sense.

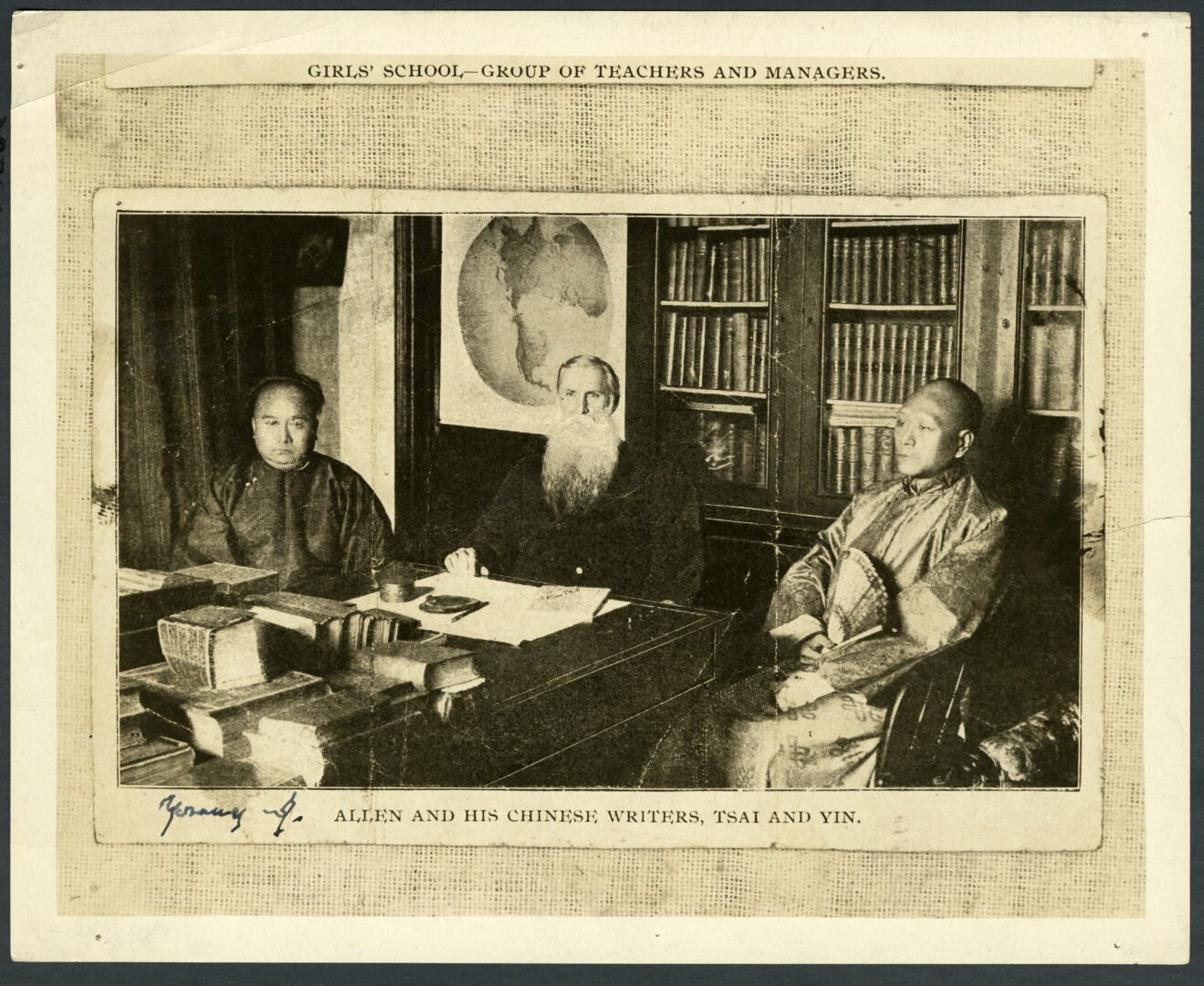

In May 1868 Allen began working as a journalist at the Shang-hai hsin-pao (Shanghai Daily News), and his work there inspired him to found the Chiao-hui hsin-pao (Church News), which later became the Wan-kuo kung-pao (Chinese Globe Magazine). His journalism served as the vehicle for a larger discussion of both Eastern and Western religion and philosophy, and the publication sometimes became his mouthpiece for condemning Confucianism. Allen was able to reach a large audience, including members of the Chinese Imperial government, by covering national and international news and other topics of interest alongside essays on more controversial topics. During his tenure in Shanghai, Allen returned to Atlanta six times for stays of varying lengths, and in 1878 he received a law degree from Emory University.

In the latter years of Allen’s life, he focused on education, especially on founding the Anglo-Chinese College and working to see it become a full university. In 1901 Soochow (later Suzhou) University, a merging of three local colleges including Allen’s Anglo-Chinese College, was founded in the city of Suzhou. During these years, he worked with Laura Haygood, another missionary and educator in the area and the sister of Methodist bishop and Emory College president Atticus G. Haygood.

Throughout his life Allen faced challenges from conservative missionaries and home boards who felt that his deviation from the standard mission plan was both misguided and beyond his responsibility of”saving souls.” Allen staunchly rejected such criticism, insisting that the best way to convert Chinese souls was through education. Even though he lived among the Chinese his entire adult life, his writings suggest that he never regarded Confucianism as anything but an atrocity. He also believed to his death that his mission was religious and that he was first and foremost an evangelist, even though his methods stemmed from social work.

Allen died on May 30, 1907, in Shanghai, at the age of seventy-one. His biography, published in 1931, was written by his longtime friend and Methodist bishop Warren Akin Candler. In 1923 the Jinlin Church was built in Shanghai to honor Allen’s life and work in China, and the Allen Memorial United Methodist Church in Oxford, Georgia, built in 1910, is also named in his honor.