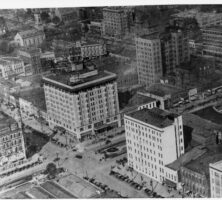

Macon, the seat of Bibb County, is the retail, medical, financial, educational, and cultural center of a still predominantly rural section of middle Georgia.

Named for North Carolina statesman and U.S.senator Nathaniel Macon, the city was established at the point where the Upper Coastal Plain rises to join the Piedmont, above which the Ocmulgee River is no longer navigable. That location makes it one of the South’s fall-line cities. While river transport was eventually replaced by rail, which a century later took a backseat to the intersection of two interstate highways, Macon’s location at the heart of Georgia’s transportation corridors has shaped its course even more than its mild climate and ample water resources have.

As the commercial hub of a productive agricultural region, the city’s fortunes were tied to a southern cotton culture that brought substantial wealth, war, and subsequently genteel poverty for its first 100-plus years. Not until the infusion of people and monies that began with military preparations for World War II (1941-45) was the stage set for a stronger, more diversified economy. Robins Air Force Base in Warner Robins (sixteen miles south of Macon), the largest industrial complex in the state, drives the region’s ongoing growth.

Early History

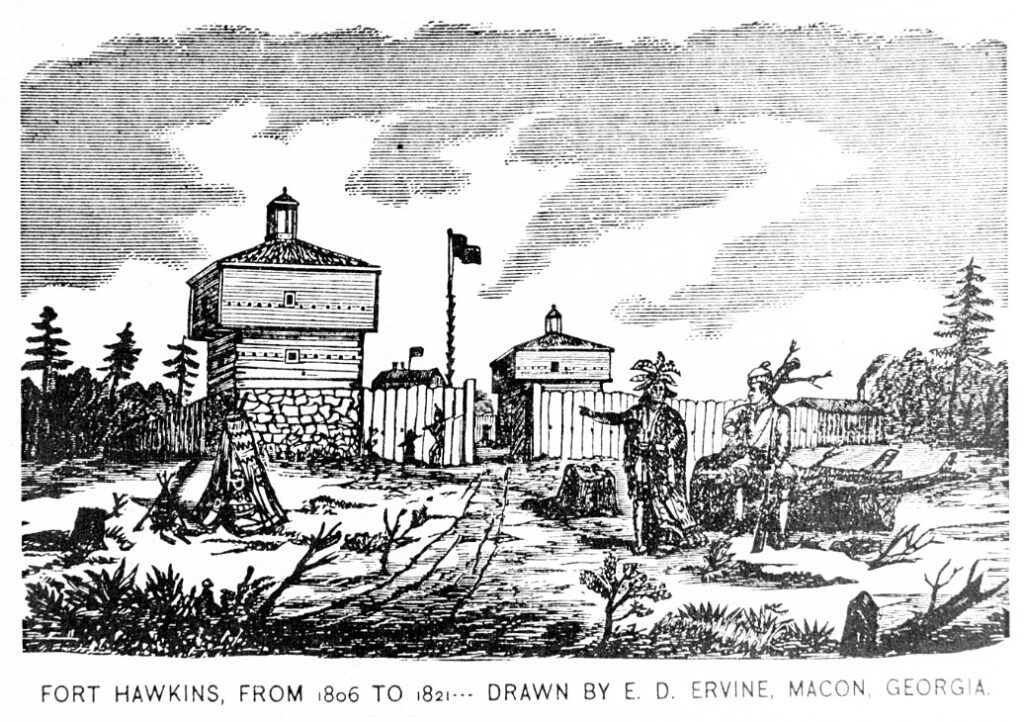

The land that became Macon/Bibb County was Indian Territory until 1821, nearly as pristine and undeveloped as Hernando de Soto found it when he rode through in 1540. Land-hungry Americans were eager to plow it into cotton fields. In 1821, demoralized by their defeat at the 1814 Battle of Horseshoe Bend, Creek Indians finally relinquished the area between the Ocmulgee and Flint rivers, as well as the Ocmulgee Old Fields, which had been withheld from the 1805 cession. Shortly thereafter the state legislature began carving the new land into counties and authorized the laying out of a town on the Ocmulgee’s west bank.

With dozens of families already living around Fort Benjamin Hawkins, the 1806 frontier outpost on the east bank that had served as post office, trading “factory,” and military supplies distribution point for more than a decade, there was no shortage of bidders when the lots were put up for auction. Building began immediately, and the town was incorporated on December 8, 1823. Farmland in the surrounding countryside, distributed by lottery, was also quickly taken: ten years later the city boasted more than 3,000 “industrious and enterprising” inhabitants who had flocked to the area from New England, New York, and North Carolina; Bibb County had more than twice that number. Cotton was selling at twelve to sixteen cents a pound, and 69,000 bags of cotton were poled down the Ocmulgee River to Darien; there were three new banks with capital of $1 million, and merchandise in stores was estimated at like value. Farmers came to Macon from more than sixty miles around to do business, and money was plentiful.

As spreading cultivation lessened rainwater runoff, however, the Ocmulgee River narrowed, and navigation soon proved impossible without constant dredging. Realizing that rail offered the best protection for their mercantile interests, Macon entrepreneurs convened a statewide meeting that led to the legislature’s decision to build track from the Chattahoochee River to Chattanooga, Tennessee—extending the reach of the Monroe Railroad they had previously launched. The same men also convinced the city of Macon to buy 2,500 shares of stock in the Central Railroad, so as to connect Macon to Savannah. Other railroads followed, and by 1860 Macon had secured its place as the intrastate center of Georgia’s 1,400 miles of track. (Atlanta’s superior connection to interstate transport was an unforeseen consequence.)

Commerce remained the backbone of Macon’s economy, but by 1860 manufacturing had gained a foothold: there were several foundries, brickyards, and tellingly, a cotton mill. Its population having grown to 8,132 (15,952 in the county), Macon was the fifth largest city in the state. Real estate was valued at $4,717,551, and personal property (most of it in enslaved laborers) at $10,279,574.

While some of Macon’s most influential citizens held Unionist views, news of South Carolina’s secession from the Union in December 1860 was nevertheless greeted with yells of excitement, firing guns, ringing bells, and a torchlight procession through town; preparations for defense began immediately. Macon-area military action during the Civil War (1861-65), however, was limited to an unsuccessful if dramatic 1864 assault from the east by an inept Yankee general bent on freeing Union prisoners while Union general William T. Sherman attacked Atlanta (just one stray cannonball fell inside the city limits).

Accordingly, Macon’s relative safety encouraged thousands of people from the surrounding countryside to take refuge in the city. Macon served the Confederate cause in multiple ways: it was a depository for Confederate gold, and its arsenal, laboratory, and armory manufactured tons of needed ordnance. Macon’s Camp Oglethorpe held prisoners of war who were officers, and many of its buildings became hospitals for wounded soldiers arriving by rail from battlefields to the north. When news of Confederate general Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, Virginia, arrived in Macon, General Howell Cobb’s prompt and cooperative surrender ensured that the Union troops occupied the city without destroying it.

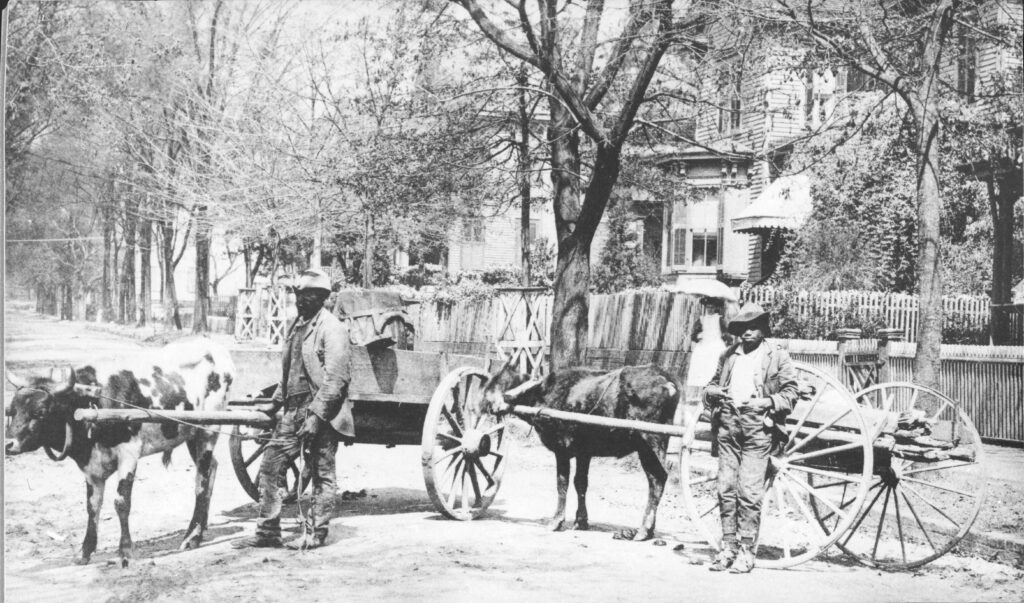

Losses from the war were more than military and political. In 1870 real estate values were comparable to what they had been ten years earlier, but personal property—reflecting emancipation—totaled only $2,697,590, a drop of 74 percent. More painful, there were 487 new widows and 913 new orphans in the city. Reconstruction saw Blacks in new roles as aldermen, legislators, postmasters, and congressmen, but that revolution was, to use W. E. B. Du Bois’s phrase, “a splendid failure” and did not last. Having won their freedom, the freedpeople soon found themselves newly tied to the land by sharecropping and tenancy systems; that, coupled with agriculture’s continued dependence on cotton, kept regional per capita income low until the boll weevil brought it even lower after World War I (1917-18). Like the rest of the South, Macon did not have the capital to develop its resources.

Still, the city managed to acquire the trappings of modern urban life: an expanded water system, sanitary sewers, telephones, electricity, streetcars, paved sidewalks, and over many years, paved streets. The Board of Public Education was established, Central City Park was developed, a city hospital opened in a former school, and a public library was organized. New citizens emigrated from outlying areas and other southern states, and the city increased its size by annexing Vineville, Hugenin Heights, Cherokee Heights, and East and South Macon. The Bibb Manufacturing Company, organized in 1876, dominated the local economy with multiple textile plants and mill villages, but the newly bred “Elberta” peach and refrigerated railroad cars brought the peach industry to life, and the organization of new banks and railroads enhanced business activity.

Later History

Macon’s active volunteer militias had joined the battle every time the United States took up arms, even (despite lingering animosities from the recent fight with the Union) the Spanish-American War (1898) and raid into Mexico to capture Pancho Villa. Soldiers had trained at camps in Macon; thus it was natural, when America’s entry into World War I became obvious, for Macon Chamber of Commerce leaders to aggressively seek military training facilities. Their efforts succeeded in bringing tens of thousands of “Doughboys” and a significant monthly payroll to Camp Wheeler, just east of Macon at Holly Bluff in 1917, and the community’s hospitable embrace of the soldiers paved the way for the camp’s reactivation in World War II (1941-45). (The Ocmulgee East Industrial Park and Macon’s Downtown Airport are now located on its site.) But World War II brought additional installations: a naval ordnance plant, a training center for British Royal Air Force pilots at Cochran Field, and most important, with the help of Congressman Carl Vinson, the enormous Robins Air Force Base for which Maconites purchased 3,108 acres in adjacent Houston County to give to the U.S. Department of Defense.

The long-term impact of these facilities, especially Robins, cannot be overestimated. They led to industrial and demographic changes that, in conjunction with social and technological changes, altered local culture in ways that continue to reverberate. If Macon had ever been, as it was once described, “more interested in the graces and pleasures of reciprocal hospitality than in commercial enterprises,” the phrase was no longer apt. The postwar boom saw northern firms establish so many new plants (to capitalize on such local resources as pulpwood, kaolin, and tobacco) that industrial employment soared from 6,500 in 1940 to 16,000 in 1949. Additionally, cotton’s grip on agriculture loosened as farmers began raising poultry, peanuts, and soybeans, and farms became larger as mechanization and migration to jobs in cities eroded the destructive tenancy system.

With non-southerners and Blacks moving into the city, and growing numbers of whites moving into adjacent counties, Macon’s social homogeneity gave way to greater diversity, a process that was significantly accelerated by the civil rights movement. The city managed to end de jure segregation without bloodshed or property damage. The burgeoning contemporary music scene may have helped to facilitate these changes; white youths broke racial barriers by attending City Auditorium concerts by homegrown Black artists Little Richard, Otis Redding, and James Brown in the 1960s. Such cultural crossover laid the groundwork for the Macon–Bibb County Convention and Visitors Bureau’s twenty-first century community brand: “Soul Lives Here.”

Macon Today

Just as Macon leaders had pushed for railroads in the nineteenth century, they sought good highway connections in the twentieth: the juncture of Interstates 75 and 16 in the 1960s, the Fall Line Freeway in the 1990s. Other infrastructure needs were not neglected. In recent decades, voters have also approved local measures to support road-improvement and local schools as well as a water treatment plant and reservoir.

The end of the twentieth century saw Macon’s economic focus shift from agriculture and industry to retail and service, with health care, financial and insurance employment, and tourism becoming increasingly important. A regional mall opened in West Macon in 1975, reorienting retail activity from downtown to the Eisenhower Parkway; The Macon Mall expanded thereafter, eventually enclosing thirty acres, before it entered a steep decline in the twenty-first century. In 2021 the mall was deeded to the local government and slated for redevelopment. The Atrium Health Navicent Medical Center (formerly the Medical Center of Central Georgia), founded in 1895, is one of four Level One trauma centers in the state and is ranked one of the 100 top-performing hospitals in the country. Nearly 10,000 people work in white-collar jobs at insurance and financial firms.

In 2012 residents in Macon and Bibb County voted to consolidate city and county governments. The newly constituted Macon-Bibb County, which features a mayor and ten person board of commissioners, took effect in 2014. According to the 2020 U.S. Census, Macon-Bibb County had a population of 157,346.

The annual Cherry Blossom Festival draws throngs during March, when more than 200,000 trees are in bloom, and the Ocmulgee Mounds, now part of the Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park, which was established in the 1930s to preserve and interpret the mounds, has been joined by more than a dozen museums and historic houses in offering year-round programs for visitors. A host of performing arts activities gives Maconites opportunities to enjoy dance, theater, and musical performances (including its own symphony) in a variety of venues. And in a swing back to the city’s roots, the revitalization of downtown led by an energetic civic effort has opened access to the Ocmulgee River via a park and greenway.

As might be expected in a more democratic era, leadership in Macon no longer rests with the business elite or elected officials; numerous citizens groups, organized and ad hoc, make their voices heard on community issues.

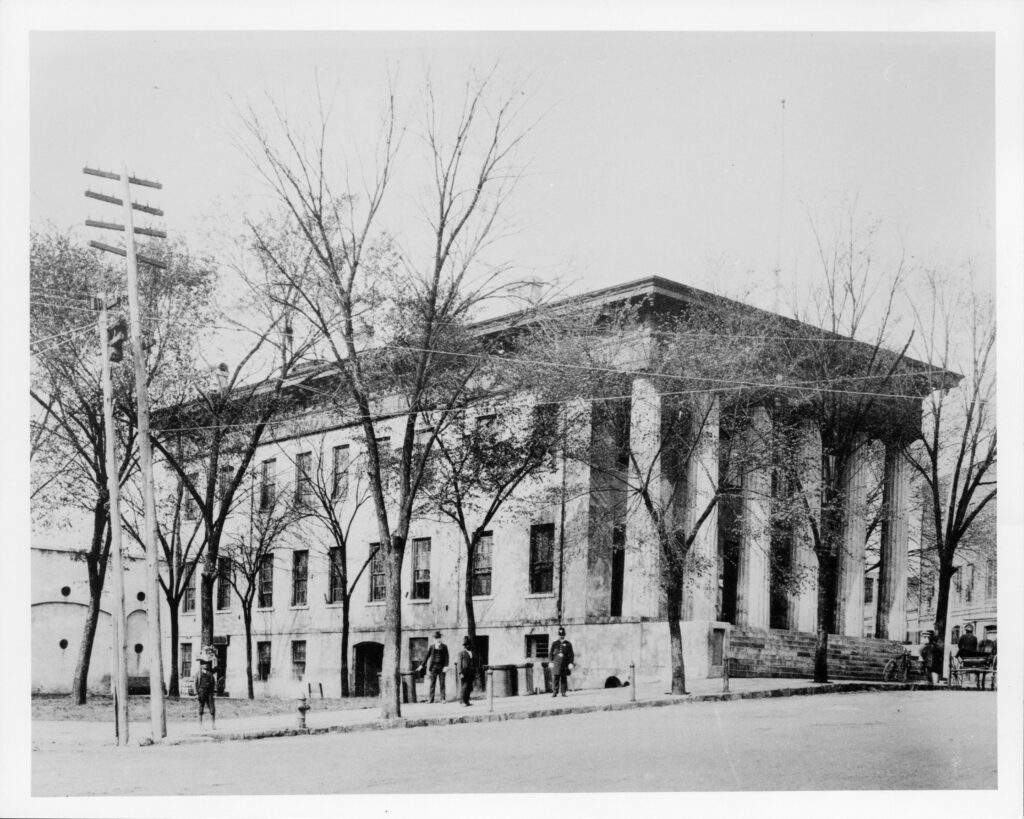

Architectural Bounty

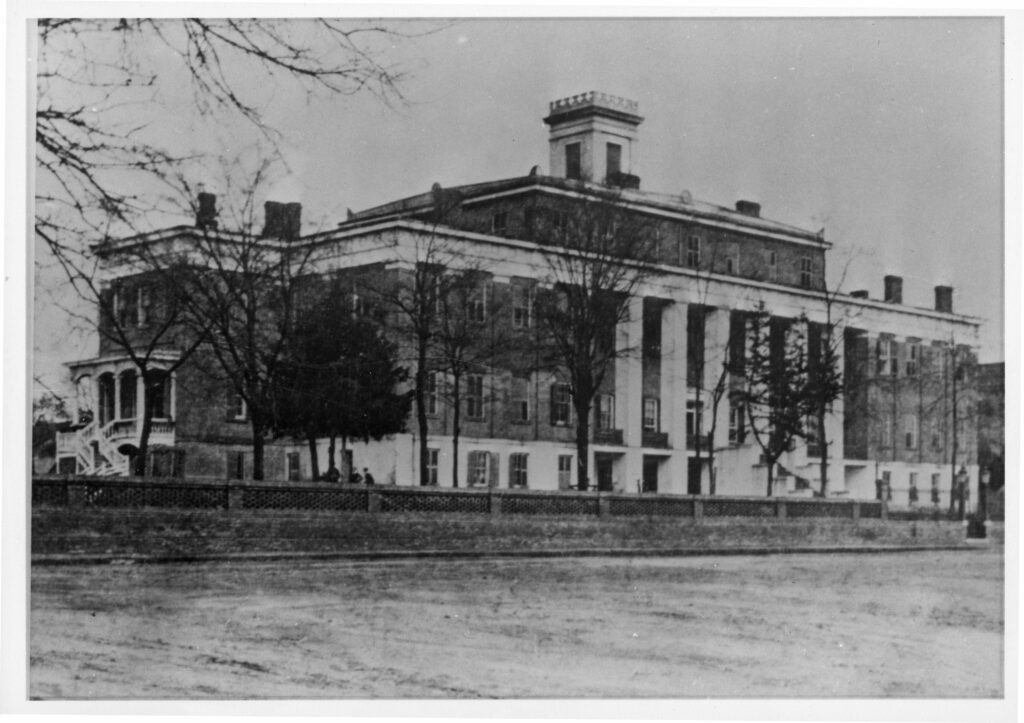

General Sherman passed to the east of Macon on his way to Savannah, sparing the city from the destruction that Union soldiers caused on their march to the sea. The pace of economic activity in Macon frequently meant adapting rather than replacing structures as patterns of commerce and living changed; as a result the city has an extensive inventory of fine old buildings, many of great historic and/or architectural significance. As of 2023, fifteen historic districts, containing more than 6,000 structures, were listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Two homes, the Hay House (open to the public) and the Raines-Carmichael House (private) are National Historic Landmarks.

Antebellum cotton wealth is still visible in what writer Bret Harte described in 1874 as “lordly houses of the great slave-owners” in the Intown and Vineville historic districts, which provide a sharp contrast to the simple frame “shotgun” houses occupied by Blacks in nearby Pleasant Hill. Greek revival, Italianate, and Queen Anne predominate, but there are many other architectural styles as well. Macon’s commercial history is written in brick and stone upon its mercantile buildings downtown. Its devotion to religious expression can be seen in the Gothic, neo-Gothic, Romanesque, and even Byzantine-influenced houses of worship located in all sections of the city.

Religion

It has been said that Macon has more churches per capita than any other city in the South; clearly, religious life has been an important part of the community from its earliest years, exerting both spiritual and political influence. The Episcopalians were the first denomination to organize (1825), joined shortly by Baptists, Methodists, and Presbyterians (1826), which entities continue in existence as Christ Church (Episcopal), First Baptist on High Street, Mulberry Methodist, and First Presbyterian. Other faiths followed: Catholics in the 1830s, Jews in the 1840s, the Christian denomination in the 1880s, Christian Scientists in the 1890s, and by the turn of the century, Adventists, Theosophists, Free Methodists, Pentecostals, Lutherans, Nazarenes, and Free Will and Primitive Baptists.

In the late twentieth century came Evangelicals, Church of God, Holiness, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Unitarians, Mormons, Muslims, and Baha’i. African Americans worshiped in their enslavers’ churches during slavery but broke into separate congregations after the Civil War and now represent numerous denominations, many of which are independent. Of the more than 250 congregations in Macon, by far the greatest number has been Baptist, with Methodist a distant second, but increasing numbers are non- or interdenominational.

Education

People who seek their fortunes in frontier towns may have a particular interest in improving the next generation; for whatever reason Macon embarked on a substantial number of educational ventures that have left significant marks on the city.

One of the earliest was the desire to establish a college “to burst the shackles of ignorance and superstition which had bound woman for three thousand years.” A group of citizens pledged $9,000 to purchase five acres on a “commanding eminence” halfway between downtown and Vineville and offered it to the Methodist Conference, which obtained a legislative charter in 1836. Thus did Wesleyan College become the first college in the United States chartered to grant degrees to women. The liberal arts school moved to a 200-acre campus in the town of Rivoli, six miles northwest of the original site, in 1928; its conservatory of music, a program close to the community’s heart, remained on Macon’s College Street until early 1953.

In 1852 subscriptions were raised to launch a school to educate blind children, after which the state was petitioned to charter and endow what continues to be the Georgia Academy for the Blind. A Negro Division, opened in 1882, was integrated into the Vineville branch in 1965, at which time the mission was expanded to include training for multidisabled children. The only residential school for the visually impaired in Georgia, the academy receives funds from the state and federal governments.

Other institutions founded in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries no longer exist but illustrate the trend: an eclectic medical college located in Macon in midcentury is credited with graduating Georgia’s first female doctor before moving to Atlanta in 1881. Pio Nono College, named for Pope Pius the Ninth, was founded by the Catholic Church in 1874 but became St. Stanislaus in 1889 when Jesuits acquired the school to train initiates for the Jesuit priesthood; it burned in 1921 and was never rebuilt.

The Georgia-Alabama Business College was established in 1889, graduating tens of thousands of stenographers, secretaries, bookkeepers, auditors, accountants, and linotype operators during its sixty-year life. Central City College was organized by the Missionary Baptist denomination in 1899 on 235 acres in east Macon, providing the only academic higher education for Blacks in Macon throughout its existence. Destroyed by fire in 1921, the college was rebuilt and continued until the 1950s, when, known at the time as Georgia Baptist College, it closed due to financial problems. Minnie L. Smith used her own financial resources to open Beda-Etta College in 1921, erecting a three-story brick building in Pleasant Hill; its course of study was primarily business and commercial.

After the Civil War, the city competed with other Georgia towns to convince Mercer University, a Baptist school founded as Mercer Institute in 1833, to move from Penfield to Macon, offering six acres west of Tattnall Square Park and $125,000 in municipal bonds. The bid was accepted, and classes began in Macon in 1871. Mercer University is the second largest Baptist-affiliated institution in the world, with a campus in Atlanta in addition to the one in Macon, and the only university of its size to offer programs in liberal arts, business, education, engineering, law, medicine, nursing, pharmacy, and theology. The medical and engineering schools have had a particular impact on the local economy, supplying doctors to rural Georgia while reinforcing Macon’s role as a regional medical center and providing engineers for the “Aerospace Alley” industries drawn by Robins Air Force Base.

Central Georgia Technical College was founded as Macon Area Vocational-Technical School by the Bibb Board of Education in 1962 and later became part of the Georgia Department of Technical and Adult Education (later the Technical College System of Georgia). Central Georgia Tech offers technical studies designed to meet the needs of employers in the eleven-county area that the school serves.

Macon leaders had sought a unit of the University System of Georgia for half a century before succeeding, via a bond issue, in opening Macon State College in 1968. Originally a two-year community college, the school grew rapidly while serving a part-time commuter student body, many of whom went on to attend a four-year institution within the University System. In 1997 the college was authorized to offer a number of critically needed four-year programs. In 2013 the school merged with Middle Georgia College to form Middle Georgia State College (later Middle Georgia State University).

Museums

Macon has a variety of historical attractions. Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park, site of a number of mysterious mounds on the east side of the river, traces 10,000 years of Native American occupation of the Macon Plateau. The Museum of Arts and Sciences presents planetarium shows and exhibitions in art, science, and the humanities. The Tubman African American Museum is devoted to interpreting African American art, culture, and history. The Georgia Sports Hall of Fame offers interactive exhibitions illustrating the history of sport in the state and honoring exceptional Georgia athletes, and the Georgia Children’s Museum offers interactive exhibitions and programs, including theatrical productions, summer camp, and a television studio. The Georgia Music Hall of Fame museum operated in downtown Macon from 1996 until 2011.

Several house museums provide glimpses of Macon’s architectural and cultural past: the Cannonball House and Museum on Mulberry Street, the only Macon home damaged during the brief 1864 assault on the city, interprets the Civil War; the Hay House on Georgia Avenue, an elaborate 1855 Italianate villa remarkable for having been among the first homes in the country to incorporate indoor plumbing and central heat, also houses notable art and furnishings. Mercer University’s Woodruff House, an 1836 Greek revival–style mansion atop Coleman Hill, is open during festivals and special events.

Just fifteen minutes north of the city in Jones County, the Jarrell Plantation State Historic Site (ca. 1840s) illustrates a medium-sized Georgia cotton plantation turned family farm. The 35,000-acre Piedmont National Wildlife Refuge is ten minutes northeast of Jarrell; it offers extensive nature trails, a wildlife drive, fishing ponds, and interactive natural history displays in its visitors’ center. The Piedmont staff also administers the 6,500-acre Bond Swamp National Wildlife Refuge in southeast Bibb County.

Thirty minutes south of Macon the Museum of Aviation at Robins Air Force Base features more than ninety aircraft and exhibitions that span a century of flight.

Performing Arts

Macon has two active community theaters. Macon Little Theater, founded in the 1930s, and Theatre Macon, established in the 1980s, offer full seasons of theatrical productions, as well as youth companies. The Macon Symphony also presents a full season and sponsors numerous outreach activities. A number of other venues offer additional cultural programming: the late-nineteenth-century Grand Opera House, restored in the 1970s, seats more than 1,000; the 400-seat Douglass Theatre, established by African American entrepreneur Charles Douglass in the 1920s and restored in the 1990s, has 70mm film capability; the Macon Centreplex, consisting of the 9,252-seat Macon Coliseum, the 2,688-seat City Auditorium (with reportedly the largest copper dome in the world), and the Edgar H. Wilson Convention Center, is the state’s largest convention complex outside of metropolitan Atlanta.

Current Business and Industry

The Macon Telegraph is Macon’s oldest business, having been in continuous publication since 1826. Owner Peyton Anderson sold it, with the now-defunct afternoon News, to Knight Ridder in 1969. Another major employer in Macon is GEICO, a direct service insurance company, which placed one of its six regional sales’ claims and services offices in the Ocmulgee East Industrial Park in 1974. The other major firm in the same industrial park is the YKK Corporation of America, whose national zipper-manufacturing center (the world’s largest) produces millions of zippers a day.

In 2006 the Royal Danish Consulate opened in Macon, the first foreign consulate in the city. A year later the Principality of Liechtenstein Consulate also opened in Macon.