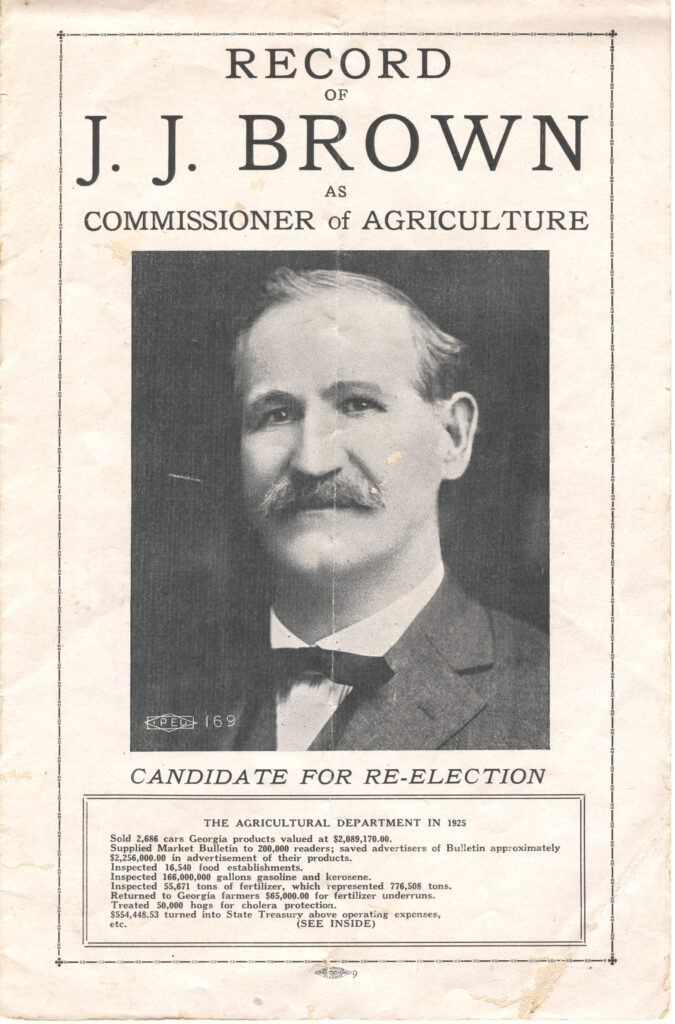

J. J. Brown was Georgia’s eighth commissioner of agriculture.

A hardscrabble dirt farmer and staunch Georgia Populist, Brown owed much of his political success to his personal and professional friendship with Thomas E. Watson. During Brown’s consecutive five terms as commissioner, from 1917 to 1927, he pushed for crop diversification, argued for legislation to facilitate landownership for tenant farmers, urged a more progressive land tax, established the Georgia Bureau of Markets, and presided over the largest food crop production at that time in Georgia history.

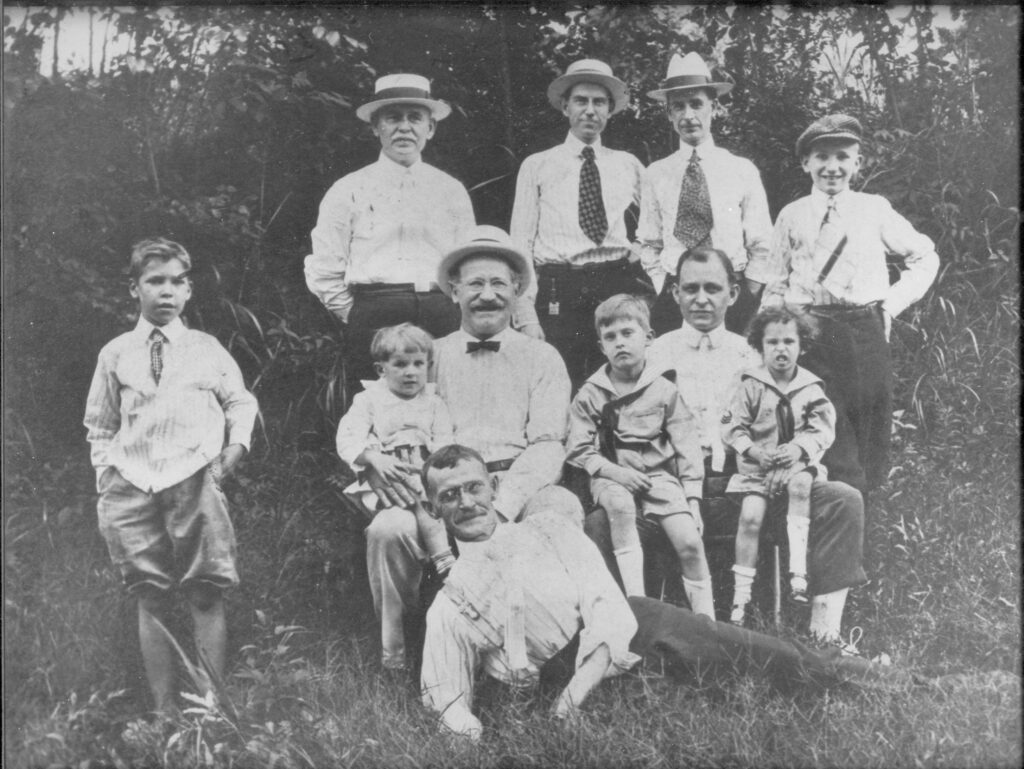

John Judson Brown was born to Susan and Ira Brown on December 17, 1865, near Vanna, in Hart County. His father ran the local grammar school, where Brown received his only formal education. In 1885 Brown married Captora Ginn. They lived on a series of farms where they eked out a meager existence raising row crops and cotton. The Browns had five children: Pearl, Polk, Sylvester, Kyle, and Walter.

Aside from cotton farming, Brown dabbled in a variety of small business enterprises. In 1895 he moved his family to the nearby town of Bowman. By 1900 he operated a general store, had established two local grain mills, and had started a company that manufactured fertilizer distributors. Around 1910 Brown was elected mayor of Bowman, his first political position.

Like Watson, J. J. Brown was a natural stump speaker and was at his best before rural audiences. In 1914 he was elected president of the Georgia Farmer’s Union, a position that helped grow his base of support throughout rural Georgia. Brown served as the first president of the Cotton States Official Marketing Board, the precursor of the American Cotton Association. He was also vice president of Watson’s Jeffersonian Publishing Company.

In 1912 Brown campaigned for the Democratic nomination for state commissioner of agriculture. Although openly endorsed by Watson, Brown lost the nomination to James D. Price. In 1914 Brown again ran for the position, this time with a campaign strategy largely crafted by Watson. Brown lost a second time, but the contest kept him in the public eye. By 1916, when he again ran for election, Brown had secured a solid following in rural Georgia. He beat Price by almost 13,000 popular votes and earned a more substantial 218 county unit votes. He took office as agriculture commissioner on February 14, 1917.

Brown had campaigned in part on a promise to create a state Bureau of Markets that would advertise crop prices and enable farmers to market their goods and services. He fulfilled his pledge immediately. Intended “to assist the farmers in the proper, efficient and economic handling, packing, transporting, distribution, and sale of agricultural products of all kinds,” the Bureau created cash markets and encouraged crop diversification. The Bureau was staffed in a matter of months with a field agent, correspondents in every militia district, and a $15,000 state appropriation. The Market Bulletin was created as a free weekly periodical to advertise farm products for Georgia farmers. By 1923 the Bulletin enjoyed a weekly circulation of 100,000. When Brown left office in 1927, the periodical had the largest circulation in the country for a publication of its kind.

Recognized as the candidate of Watson, Brown ran unopposed in 1918 and 1920. During his ten-year tenure Georgia supported the cattle tick eradication program, which helped form the basis for the cattle industry in Georgia. During World War I (1917-18) Brown initiated a state convention of farmers to encourage increased crop production for the war effort. He subsequently oversaw the state’s largest crop yields to date and did so with a farm labor shortage. When Bernard Baruch, chairman of the War Industries Board, resisted a push to include the sweet potato as an army ration, Brown successfully petitioned Congress to correct the omission.

In the election of 1926 Brown was handily defeated by Eugene Talmadge. Although he ran for the state office again in 1930 and ran for Congress in 1940, Brown was defeated both times and never again enjoyed the political clout he had earned in the 1920s. After his last campaign he purchased a large farm in south Georgia and returned to farming. During those years Brown also served on a variety of state wildlife and environmental boards and was instrumental in establishing the Okefenokee State Park and wildlife initiatives at the Clarks Hill reservoir.

In the mid-1940s, urged by his youngest son, Walter J. Brown (who had married Watson’s granddaughter), Brown moved to Thomson, where he lived his last years in Watson’s first home. He died on December 6, 1953. His funeral, hailed as “one of the last of the old-time political funerals,” was attended by numerous Georgia statesmen as well as Strom Thurmond, a U.S. senator from South Carolina, and South Carolina governor James F. Byrnes.