The Rural School Building Program of the Julius Rosenwald Fund provided financial grants for the construction of public schools for African Americans throughout the South.

The fund was established in 1917, but Julius Rosenwald began giving money for schools as early as 1912. Between 1912 and 1932, contributions from the Rosenwald Fund helped to build 4,977 new schools for African Americans in fifteen southern states. In Georgia 242 schools were constructed with the aid of Rosenwald funds, and 103 of the state’s counties had at least one Rosenwald school (Georgia had 146 counties from 1912 to 1923, and 161 counties from 1924 to 1932).

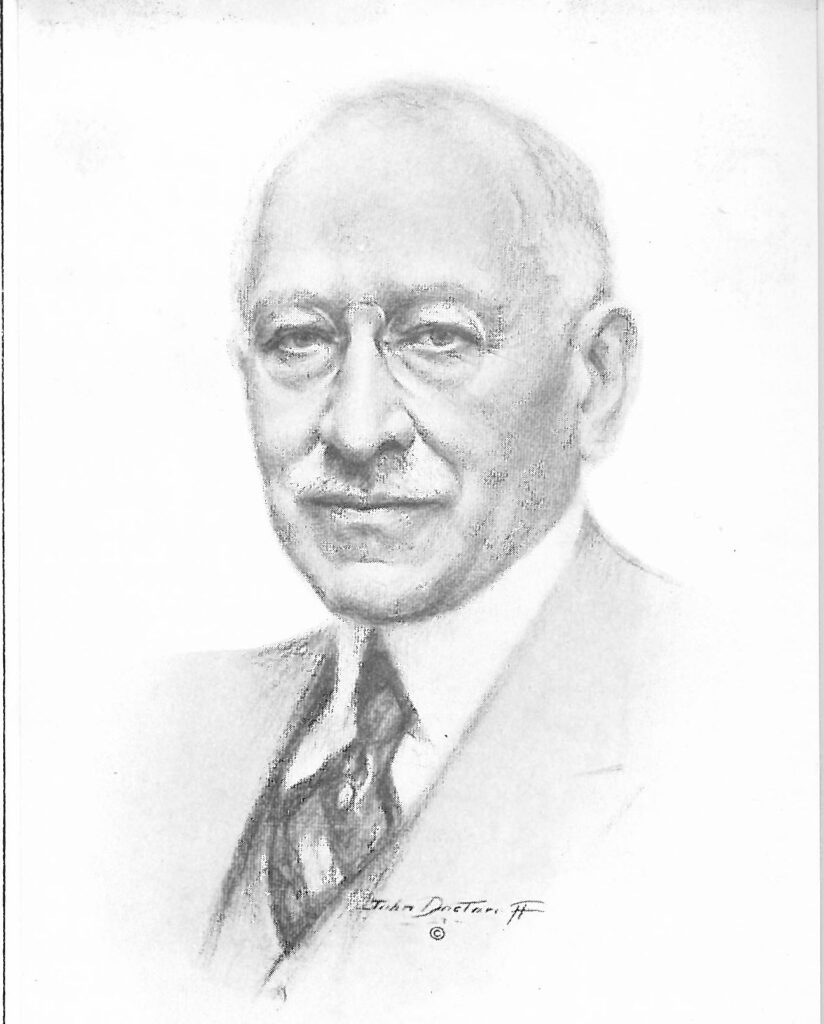

Julius Rosenwald, a wealthy Jewish philanthropist and businessman from Illinois whose charitable interests ranged from health care to colleges and museums, concentrated his efforts in the early twentieth century on improving opportunities for African Americans in the rural South. Inspired by Booker T. Washington, Rosenwald became a trustee of Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, where Washington’s philosophy of self-reliance was stressed through a program of industrial education. In 1912, on Rosenwald’s fiftieth birthday, the philanthropist gave the Tuskegee Institute $25,000 to be distributed as grants for other African American schools that followed the Tuskegee model. Washington persuaded Rosenwald to use approximately $2,000 of this money to begin an experiment in building elementary schools for Blacks in rural communities. Several small schools in rural Alabama were funded in part from the initial $2,000, and over the next four years Rosenwald contributed private funds for the construction of more than 300 rural school buildings in southern states.

In 1915 he hired a building supervisor to oversee the school construction program, and in 1917 the Julius Rosenwald Fund was incorporated. Fund officials recognized a number of shortcomings in education for Blacks in the South: a lack of adequately paid, trained teachers; the absence of high schools for Blacks; and the fact that schools for rural Blacks were open for an average of only four months per year. Yet the most visible problem was the poor condition of African American elementary school facilities. For this reason, rural school construction became the major focus of the Rosenwald Fund during its first ten years of operation. Hoping to encourage cooperation between Blacks and whites at a time when racial segregation was a way of life, Rosenwald placed certain conditions on his grants. Funds and maintenance agreements from state and county school authorities, and contributions of money, land, and labor from both Black and white communities were meant to facilitate such partnerships. Furthermore, grant amounts were based on the number of teachers to be employed.

When discussing the financial viability of Rosenwald schools, the importance of financial contributions made by rural Black southerners cannot be overstated. Because public monies were so often diverted to white schools, Black residents were forced to draw from their own limited resources to support African American education, a practice that the historian James Anderson has described as “double taxation.” In fact, seed monies provided by the Rosenwald Fund were typically exceeded by contributions made by local Black residents. According to Anderson, it was this “enduring” belief in education “that made possible and sustained the Rosenwald school building program.”

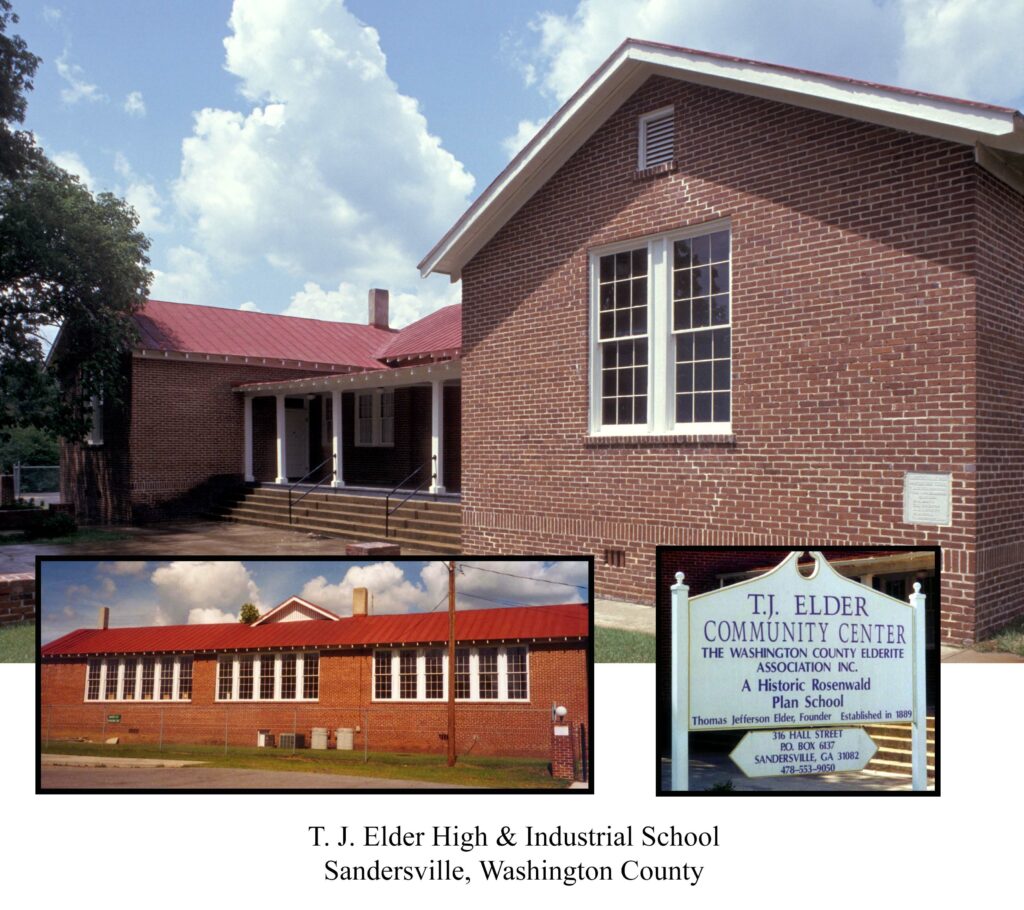

The Rosenwald Fund intended for schools receiving grant assistance to serve as models of modern rural-school architectural design. All schools were built according to standardized designs published by the Rosenwald Fund in the 1920s. These Community School Plans for simple, efficient, one-story buildings represented “state of the art” school architecture, and many schools for whites and Blacks that were not built with assistance from the Rosenwald Fund followed them. Construction specifications included exterior siding and suggested paint color schemes, brick chimneys, a small entrance porch, and tall, double-hung windows oriented toward the east or west to maximize the use of natural light. Such interior features as subfloors with oiled wooden flooring, wooden tongue-and-groove wainscoting, plaster walls, and color schemes were also specified. In addition, interior seating arrangements, the height of blackboards, and the number of cloakrooms were prescribed.

The Rosenwald Fund began to shift its focus away from school construction in 1928, as it moved toward funding other projects in education, medicine, and race relations. In 1932, the year of Julius Rosenwald’s death, the fund president announced that the Rural School Building Program would end with the close of that year. One last Rosenwald school was built in 1937 in Warm Springs to carry out an agreement made earlier between Rosenwald and U.S. president Franklin D. Roosevelt.

In all, more than 35,000 students were taught in the 242 school buildings constructed in Georgia with assistance from the Rosenwald Fund. Most Rosenwald schools were closed during the mid-twentieth century, as small rural schools were consolidated into larger, more efficient school facilities. The exact number of Rosenwald school buildings still standing in Georgia is not known. Among the surviving examples that have been identified through surveys and community interest are the Noble Hill School in Bartow County, Hiram Colored School in Paulding County, T. J. Elder High and Industrial School in Washington County, and the Eleanor Roosevelt Vocational School in Warm Springs. Records preserved in the Julius Rosenwald Fund Archives at Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee, may help communities discover others.