Beginning in the 1890s, Georgia and other southern states passed a wide variety of Jim Crow laws that mandated racial segregation or separation in public facilities and effectively codified the region’s tradition of white supremacy. The name “Jim Crow” refers to a minstrel character popular in the 1820s and 1830s, but it is unknown how the term came to describe the form of racial segregation and discrimination that prevailed in the American South during the first half of the twentieth century.

Under Jim Crow, Black Georgians suffered from a system of discrimination that pervaded nearly every aspect of life; they were denied their constitutional right to vote, encountered discrimination in housing and employment, and were refused access to public spaces and facilities. The body of law that supported the region’s system of segregation remained in place until the middle of the twentieth century, when a series of civil rights reforms, beginning with the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision and culminating with the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the 1965 Voting Rights Act, ended legal segregation in the American South.

Background

Before a raft of Jim Crow laws were passed at the end of the nineteenth century, a combination of habit, custom, and a handful of laws effectively separated the races in a wide variety of public forums. In some cases, as with the establishment of separate Black churches, Black Georgians moved to create their own local institutions in the wake of the Civil War (1861-65). More often, however, segregation occurred as a result of efforts made by white citizens to protect their racial privilege and to further limit the freedoms African Americans gained as a result of emancipation and the Fourteenth and Fifteenth amendments. State legislators passed laws segregating schools in 1872, and many cities required the creation of segregated cemeteries. Local custom often further limited Black access to public spaces, and interracial marriage was strictly forbidden by state law.

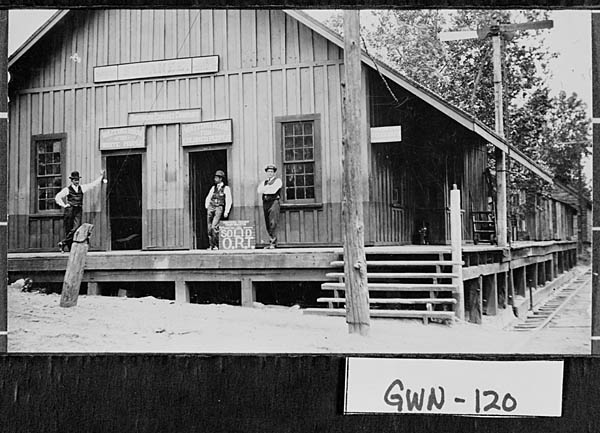

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

Despite such prohibitions, Blacks did enjoy a measure of freedom in the 1870s and 1880s that would be lost only in the 1890s and not be restored until the second half of the twentieth century. White and Black passengers routinely sat next to one another on streetcars and trains, shopped in integrated business districts, sometimes lived in the same neighborhoods, and visited the same parks and recreational facilities.

Beginning in the 1890s, however, a number of conditions contributed to the development of a more pervasive system of racial segregation. Both the widespread belief in “scientific racism” and the subjugation of nonwhite peoples in the Philippines, Hawaii, and Cuba as a result of the Spanish-American War (1898) reinforced existing notions of white supremacy. Moreover, as some historians have observed, efforts undertaken by Black petitioners in the late nineteenth century sometimes hastened Jim Crow’s rise. When confronted with Black demands for an expansion of civil rights, whites often responded by calling for a more comprehensive legal code to bar racial interaction altogether. These factors alone, however, cannot adequately explain the timing and scope of legislation passed by state governments across the South.

A more satisfactory explanation must consider the political, economic, and demographic developments that were then transforming the region’s landscape. The Populist Revolt, for one, contributed in no small part to Jim Crow’s rise. In the 1880s and 1890s, Populist leaders such as Georgia’s Thomas E. Watson attempted to fashion from the shared frustrations of poor white and Black farmers a powerful political challenge to Democratic control. Democrats, however, skillfully parried the Populist advance by appealing to the racial anxieties of whites and warning against the dangers of “negro rule”—a tactic known as “race baiting.” Thereafter, the Democratic state legislature passed a variety of disenfranchisement measures, or measures designed to limit citizens’ right to vote, including cumulative poll taxes (1877), the white primary (1900), and literacy tests (1908). Ostensibly this legislation was intended to reform the region’s corrupt politics by marginalizing Black voters, but in practice, poor whites were often stripped of the vote as well, thereby ridding the region of even the vestiges of radicalism and making southern states more attractive to northern investors.

Courtesy of Georgia Historical Society.

Perhaps even more instrumental than Populism in contributing to Jim Crow’s rise were the twin forces of economic modernization and urbanization. In the final decades of the nineteenth century, Georgians of both races flooded the state’s cities, where the region’s incipient industrial base provided an employment alternative to sharecropping and tenancy. Boomtowns in the Piedmont region profited most from industrialization, none more so than Atlanta. By the turn of the century, the metropolitan area of the “Gate City of the South” boasted more than 200 manufacturing firms, eleven railroads, and a population exceeding 100,000 people. Many observers worried, however, that the city’s rapid expansion might contribute to social dislocation, thereby weakening constraints on individual behavior and empowering Blacks to threaten white supremacy. For this reason, segregationist ordinances first appeared in Atlanta and other upstart cities throughout the region, where Jim Crow soon reached maturity as a uniquely southern expression of the Progressive desire for order and social control.

Jim Crow Begins

Many whites in attendance were noticeably anxious when Black educator and spokesman Booker T. Washington began his address at the 1895 Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta. Part debutante ball and part advertisement, the event was intended to attract northern investment and distinguish Atlanta as the capital of the New South. Although the exposition was strictly segregated, many local whites objected to the decision to invite Washington and expressed concern that the speaker might condemn the pieces of Jim Crow legislation recently passed in Georgia and other southern states.

Photograph by Wikimedia

They need not have worried. Rather than challenge Jim Crow, Washington expressed the willingness of Blacks to submit to segregation in exchange for white assistance in expanding the educational and economic opportunities available to African Americans. “In all things that are purely social, we can be as separate as the fingers,” suggested the educator, “yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress.” Known thereafter as the “Atlanta Compromise,” Washington’s speech legitimated Jim Crow policies and encouraged white legislators to pursue a more comprehensive body of laws capable of severely limiting social contact between the races.

Only one year after Washington’s historic speech, the U.S. Supreme Court granted federal sanction to the principle of “separate but equal” when it ruled in Plessy v. Ferguson against a Black man who had been arrested for riding a whites-only streetcar in New Orleans, Louisiana. The ruling also supported a Louisiana statute requiring segregated streetcars. The decision emboldened state governments across the region to expand the scope of Jim Crow legislation and step up enforcement of existing laws. “Separate but equal” restaurants, theaters, neighborhoods, and schools multiplied across the South in the wake of the Plessy decision. These facilities were usually “equal” in name only—in all the states with Jim Crow laws, the facilities that served Blacks were almost always inferior to the facilities that served whites.

Despite their limited resources, Black communities throughout the state protested efforts to expand Jim Crow’s reach. Between 1900 and 1906, Blacks in Atlanta, Augusta, Rome, and Savannah mounted boycotts of local streetcars to protest the enforcement of segregation ordinances that had previously gone unobserved. Though initially successful, whites throughout the state remained committed to Jim Crow’s defense, and protests in each city ultimately failed. When coupled with federal acquiescence, mounting regional pressure to enforce segregation overwhelmed the forces of Black resistance, and Black Georgians had little choice but to accommodate Jim Crow’s presence. Although it appeared later and developed more slowly in such older cities as Savannah, where established patricians adopted a paternalistic approach to government, segregation became a common and pervasive feature of life in all Georgia’s cities by 1910.

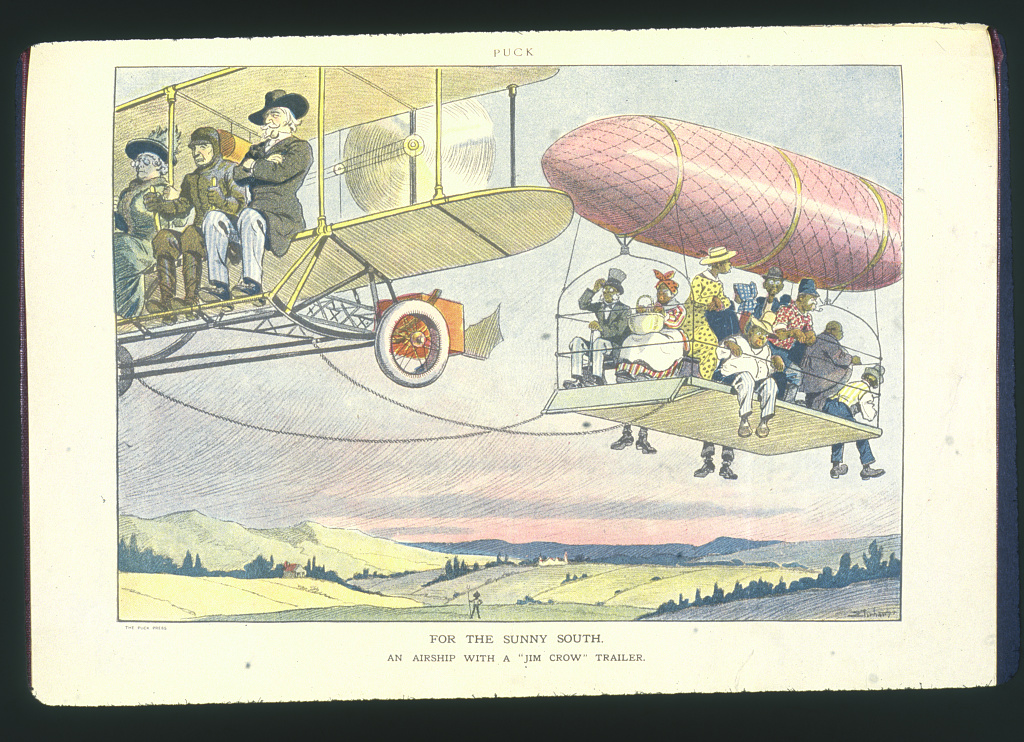

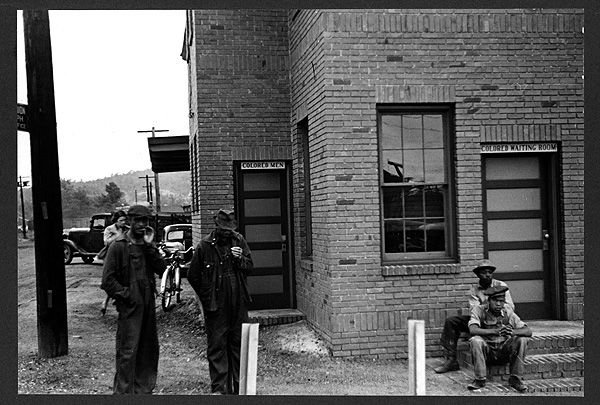

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Life under Jim Crow

Although Jim Crow’s supporters prescribed segregation as an antidote to the social upheaval wrought by rapid industrialization and urbanization, the system initially produced more conflict than consensus. As whites across the South moved to restrict Black freedom of movement, episodes of interracial violence increased in number, and an atmosphere of racial hysteria gripped the region.

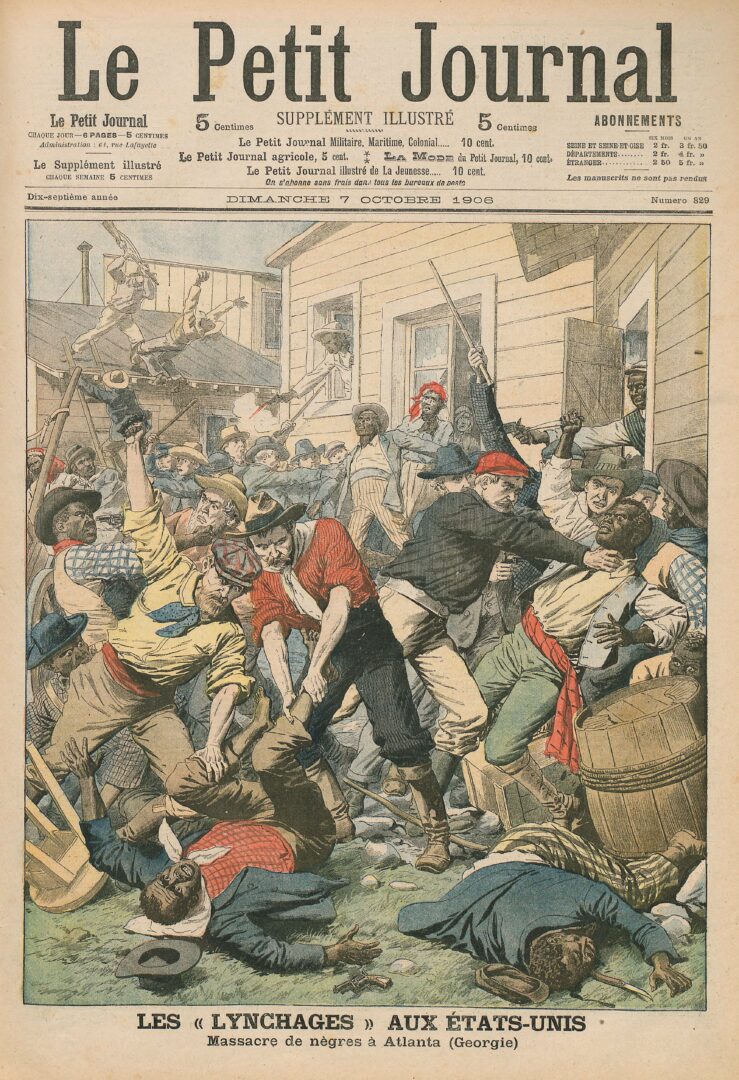

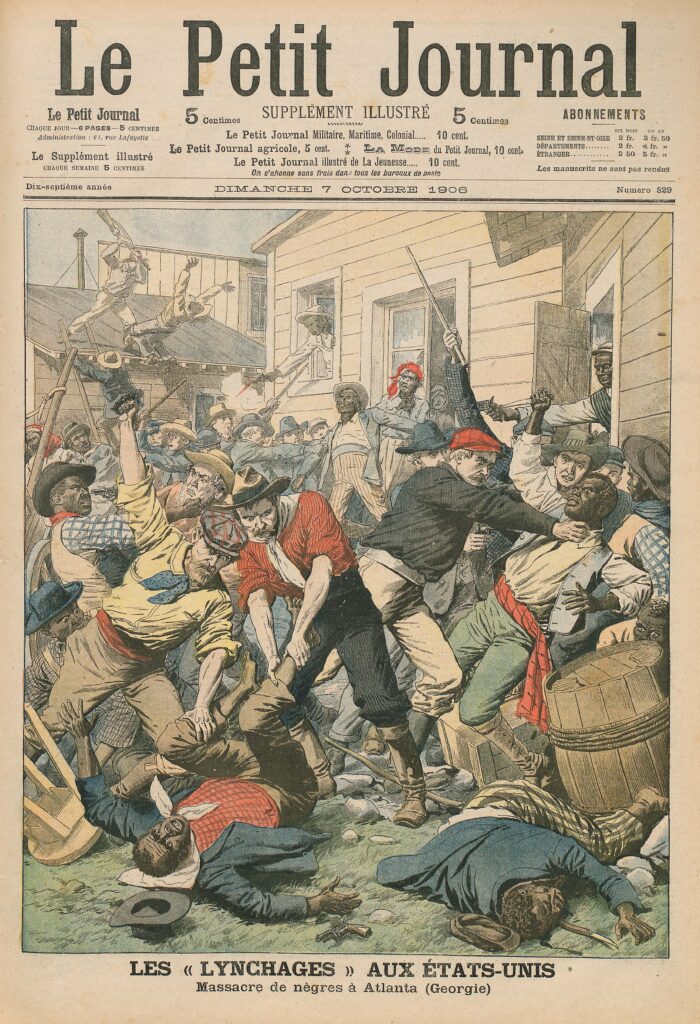

White-owned newspapers frequently inflamed racial tensions by publishing incendiary accounts of crimes allegedly committed by Blacks, often with dire consequences. Atlanta erupted in a firestorm of mob violence, for example, in September 1906, when three of the city’s evening newspapers featured stories of alleged rapes by Black men. When the dust settled after several days of violence and bloodshed, later known as the Atlanta Race Massacre, twenty-five Blacks and one white were confirmed dead. Scores more were injured, and some sources suggest that the actual number of casualties was much higher.

Elsewhere in the state, whites resorted to lynching to maintain the region’s racial caste system. Between 1882 and 1930, Georgia’s toll of 458 lynch victims was exceeded only by Mississippi’s 538. The majority of that number occurred in the cotton belt, where Blacks predominated and anxious planters expressed concern over both their Black labor supply and personal safety. In Georgia and throughout the rural South, lynching assumed enormous significance, not only because it functioned as a form of vigilantism but also because it provided a visible and ritualistic reaffirmation of white supremacy.

Passions simmered over time, however, and the racial hysteria that dominated the state at the turn of the century gave way to a rigid system of segregation that pervaded every aspect of southern urban life. Blacks and whites attended separate schools, drank from separate water fountains, worshipped at separate churches, rode in separate railroad cars, and visited separate parks and recreational facilities. When separate facilities were unavailable or prohibitively expensive, as with movie theaters or public buses, Blacks were confined to separate sections, usually at the rear.

In other circumstances, such as at hotels and restaurants, or in professional societies, Blacks were often refused admission altogether. Black Georgians were also denied their rights of citizenship; most were unable to vote, and precious few ever sat in a jury box. Limiting Black representation in juries was an especially effective means of upholding white supremacy. Many Black victims of violence couldn’t count on all-white juries to fairly judge their cases. Should they ever be summoned to court for another purpose, however, Blacks were sworn in with separate Bibles. While they may have always been separate, public facilities, expenditures, and spaces were rarely, if ever, equal. Here, state education spending may be most illustrative. Despite spending about $43 per white student in 1930, Georgia spent only about $10 on each Black student in the state’s public school system.

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

While they provided a critical legal framework for white supremacy, segregatory statutes were actually relatively few. Perhaps more significant than the body of law upholding Jim Crow was the complex system of racial etiquette that governed all interaction between the races. According to the region’s racial protocol, all Blacks were required to pay obeisance to all whites, even those whites of low social standing. And although they were required to address whites by the title “sir,” Blacks rarely received the same courtesy themselves. They were usually called “boy” or “old man,” regardless of their age. Because even minor breaches of racial etiquette often resulted in violent reprisals, the region’s codes of deference transformed daily life into a theater of racial rituals, where every encounter, exchange, and gesture reinforced Black inferiority. Black men, for example, were expected to remove their hats when they talked to white men, and most restaurants did not serve Black customers in the dining room—Blacks were expected to order at the counter, and then wait for their food outside. Occasionally Black customers might be allowed to eat in the restaurant’s kitchen. As Georgia author Lillian Smith notes in her 1949 memoir, Killers of the Dream, Jim Crow’s racial etiquette amounted to a “crippling dance” that white and Black southerners learned at an early age:

From the time little southern children take their first step they learn their ritual, for Southern Tradition leads them through its intricate movements. And some, if their faces are dark, learn to bend, hat in hand; and some, if their faces are white, learn to hold their heads up high. Some step off the sidewalk while others pass by in arrogance. Bending, shoving, genuflecting, ignoring, stepping off, demanding, giving in, avoiding. . . . So we learned the dance that cripples the human spirit, step by step by step, we who were white and we who were colored, day by day, hour by hour, year by year until the movements were reflexes and made for the rest of our lives without thinking.

While the experience of Jim Crow was no less harsh in rural areas, and in fact may have been more so, it did lack the rigidity that characterized urban segregation. In Georgia’s cities, segregation developed as a solution to the problems posed by modernization and urbanization. However, rural Georgia remained a largely premodern society, making many features of segregation unnecessary or even problematic. As historian Mark Schultz demonstrates, rural race relations were typically marked by personal intimacy and a “culture of localism.” Similar patterns of deference prevailed in rural race relations, but local governments in rural Georgia were more likely to depend on custom, rather than law, to maintain white supremacy.

Although Black Georgians experienced little political progress under Jim Crow, many did achieve an impressive measure of economic success. While some Black farmers made the jump from tenant to landowner in rural Georgia, the majority of Black economic development occurred in urban areas, where a small but significant class of Black professionals emerged.

Throughout the first half of the twentieth century, large numbers of Blacks moved to the state’s burgeoning urban locales, creating a captive market for enterprising Black businessmen. Black-owned groceries, restaurants, funeral parlors, and clothing stores then emerged to meet increased consumer demand. Most were small, owner-operated outfits, but collectively they formed a commercial bedrock in developing Black business districts, such as Augusta’s Golden Blocks neighborhood and Atlanta’s Auburn Avenue. Of these, Atlanta’s Auburn Avenue was most significant. Many of the South’s most successful Black professionals called “Sweet Auburn” home, and in 1956 Fortune magazine memorably called it “the richest Negro street in the world.”

Courtesy of Georgia Department of Economic Development.

Still, the success experienced by a handful of Black businessmen under Jim Crow should not obscure the discrimination and lack of opportunity that stifled the efforts of most Black workers. The majority of the state’s Black population still resided in rural areas, where the crop lien system ensured that poor farmers of both races would endure cycles of debt and dependency. In urban areas, Black men were excluded from all but the most undesirable manufacturing positions and usually had little choice but to accept employment as unskilled laborers, while Black women most often worked as domestic servants in white households. During periods of economic distress, such as the arrival of the boll weevil and the Great Depression, Black workers were the first to lose their jobs and usually suffered disproportionate hardship. New Deal programs and wartime employment increased pay scales throughout the region, but despite assuming a larger presence in Georgia and other southern states, the federal government did little to alter discriminatory employment practices.

Challenging Jim Crow

Throughout the first half of the twentieth century, Black Georgians continued to mount isolated protests against Jim Crow by petitioning local governments, organizing public demonstrations, and undertaking other, more subtle forms of resistance. A handful of prominent white Georgians supported their efforts as well. Author Lillian Smith and Atlanta Constitution editor Ralph McGill advocated racial moderation in their writings, while Clark Foreman and Will Alexander encouraged interracial cooperation and democratic reform through their efforts with the Southern Conference for Human Welfare. Without widespread support or political power, though, most efforts remained ineffective and personally perilous for Blacks. At the end of World War II (1941-45), however, a series of national and regional developments began that ultimately brought an end to Jim Crow’s “strange career.”

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

In 1946 the white primary in Georgia was invalidated by a federal court ruling in favor of Primus E. King, a Black citizen denied the chance to vote in Columbus. The decision opened the doors to greater Black political participation in the state. Within a matter of months, more than 116,000 Blacks registered to vote, signaling a major shift in the state’s political landscape. Black political participation was initially greatest in Georgia’s urban areas, where the organization of influential voting blocs positioned Black communities to win concessions from municipal governments by forcing white candidates to compete for Black votes. However, because whites maintained a tight grip on the electoral process in Georgia’s rural sections, and because the county unit system caused state Democratic primaries to favor rural votes, statewide reform would have to await federal intervention in the 1960s.

At the same time, an increasing number of national observers agreed that ending segregation was both a moral and diplomatic imperative. In An American Dilemma (1944), Swedish economist Gunnar Myrdal explores the internal conflict that allowed ordinary Americans to support the promotion of democracy and freedom abroad, while condoning segregation at home. The book’s publication began a national conversation regarding the desirability of race reform, the contradiction between segregation and cold war policies, and the proper role of the federal government in ensuring equality under the law. Thereafter, U.S. president Harry Truman moved to desegregate the nation’s armed forces, and the U.S. Supreme Court issued decisions in Sweatt v. Painter (1950) and McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents (1950) that whittled away at the precedent established by Plessy a half century earlier. By 1954, when the Court repudiated altogether the dubious logic of “separate but equal” in Brown v. Board of Education, a national consensus existed to end segregation in the South.

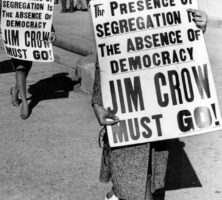

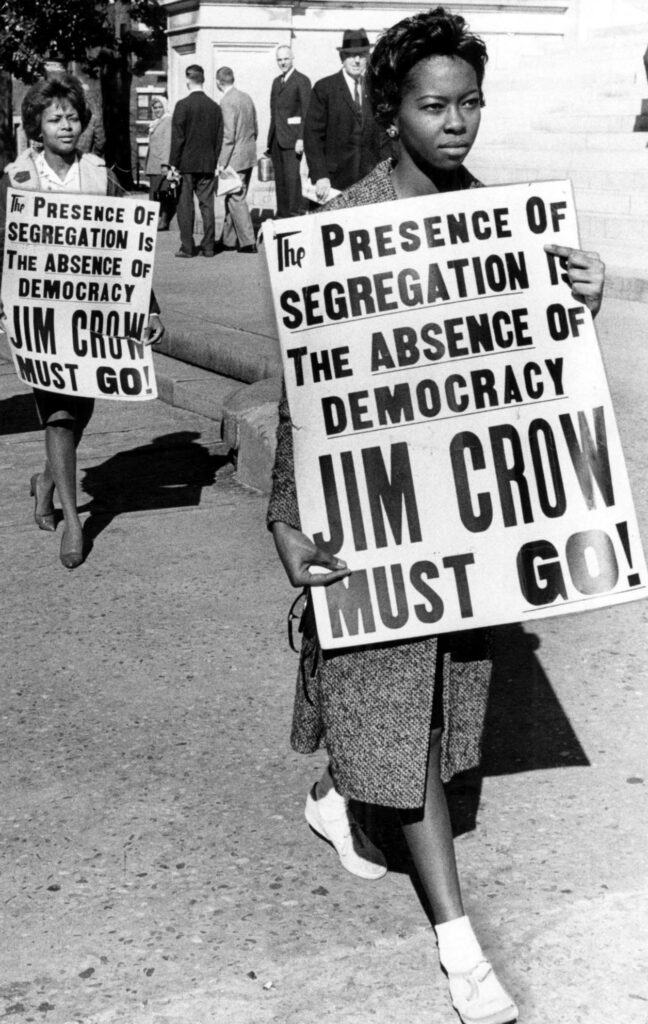

Despite the slow pace of integration, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People continued its campaign to dismantle Georgia’s Jim Crow legal system, bringing suit to desegregate Atlanta’s public golf courses, schools, and buses during the 1950s, as well as representing Black plaintiffs (Hamilton Holmes and Charlayne Hunter) denied admission to the University of Georgia in 1961. Blacks throughout Georgia and the region meanwhile organized on an unprecedented scale to lobby for an end to legal segregation. Albany residents, for example, with the assistance of Martin Luther King Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, launched an ambitious, though ultimately unsuccessful, desegregation campaign, which came to be known as the Albany Movement. Meanwhile, Black college students in Atlanta staged sit-ins to force the desegregation of area lunch counters. As a result of these and similar efforts throughout the state and region, the U.S. Congress passed the Civil Rights Act in 1964 and the Voting Rights Act in 1965, bringing an end to legal segregation in the United States.

Courtesy of Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

Despite the passage of federal civil rights legislation, public facilities in Georgia and throughout the region remained segregated in many areas well into the 1970s. Even as recalcitrant communities succumbed to federal pressure, de facto residential segregation remained a common feature in many locales throughout the state. Atlanta’s indices of residential segregation actually increased between 1940 and 1980, as middle-class whites abandoned urban residential areas for new developments on the suburban periphery. Similar developments occurred in other cities throughout the region, and today the persistence of segregated residential patterns in contemporary southern communities attests to Jim Crow’s enduring legacy.